I looked up and saw only the gray and empty winter sky in the space I'd always before seen filled by the soaring needle-spired tower of the Chrysler Building. I glanced down, and where the base of the Chrysler Building belonged stood the round little red-brick-and-white-stone tower you see in my sketch, no more than a dozen feet taller than our tracks. And in that moment — the moment of my sketch — moving through this partly familiar yet utterly strange and now suddenly hostile city, I felt a rush of homesickness nearly overwhelm me; I had to close my eyes for a moment to fight it off.

Within seconds we were slowing down, backing in between the twin arms of the station platform at the other end of the two-block spur line. It wasn't impossible that the two cops could hurry along Forty-second Street for those two blocks, even commandeering a carriage or wagon for all I knew, and I stood in the doorway of the engine cab staring ahead at the Third Avenue line, hoping a train we could transfer to would be just coming in. But there was none even in sight, and the moment the wooden floor of the station platform appeared beside me, I hopped off the engine — I don't think the engineer ever did see me — and let my own momentum carry me trotting forward to the slowing car just ahead. Julia was standing at the gate, the conductor right behind her. "That's against the law, you know!" he said angrily to me. I wasn't sure whether he meant lifting Julia over the gate or riding the engine, and I said I was sorry, and handed him our tickets. Then — I wanted to yell at him to open the gate but was afraid if I did that he'd be deliberately slower than ever — he got out his punch, carefully punched both tickets, handed them back to me, and I thanked him. And only then did he open the gate and let Julia off. Then we ran for the stairs.

I think the two cops could have been there if they'd really tried, waiting for us to step down off the stairs onto the walk at Third and Forty-second. But they'd have had to move faster than they'd done in some years, and no one grabbed us. But across the street a cop walking his beat looked into a saloon over the tops of the two waist-high latticed doors of the entrance, then strolled to the curb at the corner, and stood, skillful as a professional entertainer, bouncing and twirling his club at the end of its thong. I had the feeling that he'd given far more time to club twirling than crook catching, and as we turned and walked south on Third Avenue, moving away from him as fast as we could without obviously hurrying, I was glad that this was his beat. Julia was looking at me questioningly, and I understood. Were our photographs in his helmet, too? I shrugged; if not, they would be soon. Every cop in the city would have them, to be passed on to the next shift, and with extra cops and probably plainclothesmen out, too. The reward Carmody had almost openly offered Byrnes would be big if we were caught and convicted, or "killed while escaping"; it wouldn't matter which. Because Byrnes was clever: Our «escape» and flight, of course, would be accepted as confession.

The cop on the corner was half a block behind now and hadn't even glanced at us. But the next one could be different, and if he wasn't, then the one after that. We simply could not walk through the streets for block after block; we'd be caught within minutes. And any public transportation would be as bad. We had to get off the streets right now: into a hansom, it occurred to me longingly, where we could sit back and move unseen through the streets with time to think. But Byrnes knew the problems of people trying to hide; it takes money, and he had ours.

"Julia, have you any friends who'd hide you for a few days, lend you some money?"

"In Brooklyn, yes; we lived there up until two years ago. But the only friend here I could ask to do that lives at Lexington and Sixty-first, and —»

"Too far, too far!" I got rattled. "Where are we, Julia, Forty-first? What's the nearest bridge? Maybe they aren't guarding them yet, and we can still —»

"Si, there's only one bridge, Brooklyn, and it's way downtown."

I nodded, glancing at store windows we passed, trying to see whether they reflected anyone following or about to challenge us. More than ever before, I was realizing that Manhattan is an island and not a very big one, either; you can walk its circumference in a day. "I don't want us to be trapped sitting on a ferry like a couple of pigeons. We need money, dammit! To hole up in a hotel where they can supply our meals. Suppose we telephoned your aunt — " I stopped.

"Did what?"

"Never mind."

But she'd heard me. "I don't know anyone who has a telephone. Or who has even seen one."

"I know, I know!"

"We could send a messenger boy; there's an office near here."

"But we'd have to wait there for the reply?"

"Yes."

"When the boy came back, the cop that I'm certain must be watching the house would be right along with him. God, how I wish there were movies! Between us we probably have the price of a cheap one, and we could sit and wait till dark."

"Movies?"

I'd lose my mind if this kept up. I said, "We've got to separate, Julia. Till dark. They're looking for the pair of us; let's not make it easy for them. It'll be dark in forty minutes, an hour at most. And I'll try to sneak in and out of the house then; I've got money in my room. Meet me in a hour and a half at — where's the nearest good place from the house? — in Madison Square. Walk through it as though you're going somewhere, and I'll follow you out. If I'm not there, try again in half an hour. Then give me up, and" — I shrugged — "do your best. Okay?" Before she could answer I looked at the windows of a store we were passing; the entranceway passed between double display windows, one pane of each set at a 45-degree angle to the walk. It reflected the half block or so behind us and I saw a man running silently toward us. He was in plainclothes, wearing a derby and a long topcoat, but nothing could disguise the truth that he was a cop. He was running on his toes without a sound, and he was about the length of a football field behind. Without turning around I spoke quietly and very rapidly. "Julia. You must run. To the corner, and around it, and keep on. Do it now, now!"

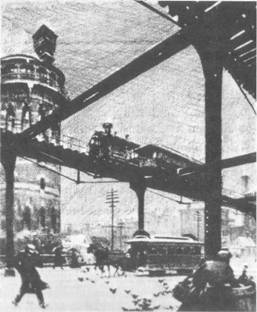

She didn't hesitate or waste time looking back, but gathered up her skirts and ran. I turned and walked straight out into the street. There I turned to face the sidewalk and stood waiting. And now the man running toward us had a choice to make between me or going after Julia, leaving me behind his back, and not sure what I'd do. He had to choose me, and he did it cleverly, running right past me as though going for Julia, as I thought he was for a moment. Then he whirled in a fast right-angle turn and came at me. But I'd picked a metal pillar of the El tracks to stand near, and I stepped over to it. For a moment or so we stood, both of us balanced on our toes, the pillar between us, trying to out-feint each other. Then he lunged, I shoved off hard from the post, and he was after me.

But he could shoot and probably would if I began outracing him, and at this distance he wouldn't miss. Running on was pointless, and I did the only other thing left to do. I whirled and literally threw myself at his ankles in an action he may not ever have seen before — a football tackle, though this was from the front. I'd played a little football in high school before the players got too big for me. And now I hit his shins with my left shoulder, my arms wrapping tight around his knees in a tackle so illegal it would have drawn a hundred-yard penalty — and he went right on forward over my shoulders and down onto cobbles. I thought my shoulder was broken — the numbness reminded me of why I'd had to quit the game — but I was up right away and running in the opposite direction. I looked back; he was still lying on the street. Fifteen more running steps right down the middle of the street, wagon drivers turning to stare, then I looked back again. He was on his knees, turning to face me and pulling a big nickel-plated revolver from his back pocket. I stayed on the side of the line of pillars opposite him, and kept glancing over my shoulder in a series of fast peeks. Using both hands, he was aiming carefully; he wanted me, all right. I slowed suddenly, then sprinted, trying to throw his aim off; he fired, and the bullet struck a pillar, making a surprisingly loud clang. People stood frozen on the walks, but none of them seemed to want to come out into the street. At the corner I turned and ran east in the direction opposite from Julia's, and the gun roared again, and I mentally examined myself and decided I hadn't been hit.