The roof was a shingled many-gabled complexity of windowed pyramid-shaped towers of various sizes; rising from their center, and highest of all, was an ornate square tower surrounded at its base by a fenced walk. WESTERN UNION TELEGRAPH CO. was painted in a circle on the side of the tower, and now I saw that a great many of the wires lining the street originated from this rooftop. A flagpole rose from the roof of the tower, an American flag fluttering rapidly from it; and at the top of the pole directly behind the flag I saw a large bright-red ball. The ball was made with a hole through it apparently, like a doughnut; it surrounded the pole and must have been visible up there for miles around.

I didn't know what was going on, but I got out my watch — two minutes to twelve, it said — and stood like the hundreds of other men all up and down Broadway as far as I could see. Suddenly, and there was a simultaneous murmur, the red ball dropped the length of the flagpole to its base, and the man next to me murmured, "Noon, exactly." He carefully set his watch, and I did the same, pushing the minute hand forward. All around me I heard the clicks of the covers of gold watches snapping shut. The hundreds of men at the curb turned and became part of the streams of pedestrians again, and I was smiling with pleasure: Something about this small ceremony, momentarily uniting hundreds of us, appealed to me mightily.

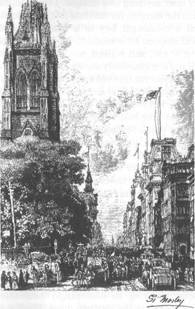

Now, just past the stroke of noon, music — chimes — had begun somewhere behind me, and I knew the tune: "Rock of Ages." I turned to look back, and smiled. I'd seen the source of the sound just down the street: it was an old friend, Trinity Church, its chimes clear in the winter air, and I hurried along to it. Then, a couple of dozen steps past the church, my back against a telegraph pole out of the stream of pedestrians, I made a quick reference-sketch which I finished up much later. I'd sketched Trinity before, but this time, incredibly, its tower rose black against the sky, higher than anything else in sight. I finished, making notes in the margins for the final job, stood looking at it, and a messenger boy in a brass-buttoned blue uniform stopped for a moment, looked at my sketch, nodded at me, and walked on. This is the finished sketch and it is absolutely accurate except that I added leaves to show the fine old trees more clearly. This is the Broadway I walked along — in the middle distance at the left you can see the Western Union Building and the time ball which had just dropped to the base of the pole a few minutes before.

Walking back, glancing down at my rough sketch, I was tempted to stop and add the ghosts of the tremendous towers that would someday surround Trinity, burying the tower at the bottom of a canyon. But I was passing the church entrance now, and four or five men hanging around on the sidewalk before it, sizing me up correctly, called, "Visit the steeple, sir! Highest point in the city! Best view in town!" There was just time, and I nodded to the one who looked as though he needed the money most.

Inside he led me up a steep endlessly winding stone staircase, on up past the bell-ringing rooms, then past the bells, clanging so deafeningly here that you couldn't make out the separate notes. Finally, at the top, we reached a wooden-floored ledge running under several narrow open windows. My knees felt the climb, and I was trying to hide my puffing. I reached out and tried one of the stone windowsills, making sure it was solid, and the guide laughed. "I was waiting to see whether you'd try that sill; they all do. Not one man in ten will lean up against it till he's sure it'll hold. I've had men up here wouldn't stand within two feet of it when the windows was open. And I've had ladies get sick the minute they looked down." He kept up the chatter while I looked out: The steeple was 284 feet high, he said; it was the highest point in the city, 16 feet taller than even the Brooklyn Bridge towers, and the church stood on a higher piece of ground besides. At least 5,000 people visited this steeple every year, and probably more, but very seldom a New Yorker alone; no one had ever tried suicide by jumping; and so on and on, while I stared out at the entire upper Bay.

The sky was steel-gray, the air very clear, everything sharply etched. Over the low rooftops I could see both rivers, the water — of the Hudson especially — ruffled, gray as hammered lead. Lining South Street off to my left were hundreds and hundreds of masts; I watched the ferries, great paddle wheels churning; I stared out at the church spires high over the rooftops in every direction; I saw the astonishing number of trees, to the west especially, and thought of Paris again; and I looked down at the walks onto the heads of passersby in Broadway, the tiny circles which were the tops of silk hats tilting and winking dully in the clear winter light. At an opposite window I looked uptown, across the roof of the post office toward City Hall Park. Beyond it, off to the east and sharp against the winter sky, stood the great towers of newly cut stone supporting the immense cables from which the roadway of Brooklyn Bridge would hang; now I could see workmen moving along temporary planking laid here and there across great open gaps of the unfinished roadway, the river far below clearly visible.

It was a great view of the city from what was, of course, the day's sightseeing equivalent of the Empire State Building far in the future. But there was nothing laughable in the comparison, I thought, staring out at the city; this was the highest view in town just now, however lost among incredibly higher buildings it was going to become. And if someday I'd have to go up ninety-odd stories to get a murky, smog-ruined view of New York instead of this brilliantly defined closer look at a lower and far pleasanter city, then who should be doing the laughing? I wanted to sketch the view, but it would have taken hours just to rough it in, and now I had to hurry. Downstairs I gave my guide a quarter, which made him happy; then, moving fast, I walked back toward City Hall Park.

14

At twenty-four minutes past noon, standing at a first-floor rear window of the post office, I stood looking across the street to the north at the little wintertime park and the people moving along its crisscrossing paths, and the strangeness of what I was doing took hold of me. Staring out that soot-dirtied window, I was remembering the note I'd seen in Kate's apartment, the paper yellowing at the edges, its once-black ink rusted with time. And the meeting in this park, arranged by that note, became an ancient event, decades old and long since forgotten.

Could it really be about to happen? I wasn't able to believe that it would. People, strangers, continued to walk out of and into the park and along the walks all around it. Just ahead and across the street to my right, Park Row, stood the five-story New York Times Building I'd seen the night Kate and I walked to the El station, and again it was strange knowing it still stood in twentieth-century Manhattan. Now in daylight, I read the long narrow signs, suspended just below windowsill level, of other lower-floor tenants of the building: FOREST, STREAM, ROD GUN… LEGGO BROS…. The Times Building shared a common wall with another five-story stone building right behind it almost directly across the street to my right. It was nondescript, with tall narrow windows, its front — like the Times Building beside it and like most other such buildings in this area — hung with narrow gilt-on-black or black-on-white signs suspended just below the windows of the tenants. Then my eyes dropped to the street-level entrance, and Jake Pickering was standing in it.