In almost that moment it began to snow, the flakes tiny and scarce. But within half a minute, in only the time it took the woman walking toward me to reach Irving Place and turn into it, disappearing from my sight, the flakes had thickened. Then they flew fast, swirling, beginning to cover the walks, the paths, the stone steps and stoops, beginning to mound on the heads of the iron horses.

It was too much, I can't really say why, and I turned from the window and lay down on the long single bed, careful to keep my feet off the plain white bedspread. And I closed my eyes, suddenly more homesick than any child. It occurred to me that I literally did not know a single person on the face of the earth, and that everything and everyone I knew was impossibly far away.

For an hour, maybe a little less, I was asleep. Then occasional voices, the sounds of doors opening, closing, and footsteps in the hall pulled me awake. The room was dark now, but the slim rectangles of the windows beyond the foot of my bed were luminous from the new snow outside. I knew where I was, swung my legs to the floor, and crossed the room to the windows.

Streetlamps glowed around the square, the snow sparkling in the circles of light at their bases. To my right and just around the corner of the square a carriage door slammed, and I turned to see the reins flick on the backs of two slim gray horses. Then the carriage started toward me, its sides shiny-black in the light of its own side lamps. Almost immediately, its high thin wheels leaving blade-thin tracks, it entered a cone of lamplight, bursting into black-enamel and plate-glass glitter. Through the glass of my windowpane I heard the faint jingle of harness and the muffled clippety-clop of shod hoofs in new snow. The carriage turned the corner, and I stared down at the foreshortened figure of the driver, high on the open front seat, neatly blanket-wrapped to the waist, reins and whip in his gloved hands. Horses, driver, and carriage passed directly under my window; I looked straight down onto the harnessed gray backs, the jiggling top of the driver's silk hat, and the dull black of the carriage roof. Once again horses and carriage moved glitteringly through a cone of yellow light, and I watched then-shadows thin to nothingness on the new snow. The shadows reappeared, thickened, turned solidly blue-black, then raced on ahead of the carriage, lengthening and distorting. Now, in the oval rear window, two heads were framed, a man's under a top hat, and a woman's bare head; I saw her hair bound up in a bun at the back. The man turned to the woman, said something — I could see the movement of his beard — then the carriage turned the corner, and I saw its side light, saw the horses disappear; then the carriage itself was gone, except for its thin double tracks. And an exultance at being here in this time and this city raced through me. I swung away from the window, pulling off my coat, walked to the dresser, poured water from pitcher to bowl, and washed. I put on a clean shirt, tied my tie, combed my hair, and walked quickly to the door, the hall, the house, and its people.

A thin young man in shirt-sleeves carrying a shallow pan of water came walking along the hall toward me from the bathroom. He had dark hair parted on one side, and a brown Fu Manchu mustache. The instant he saw me he grinned. "You the new boarder?" He stopped. "I can't shake hands" — smiling, he gestured with his chin at the pan he held — "but allow me to introduce myself. I'm Felix Grier. Today's my birthday; I'm twenty-one."

I congratulated him, told him my name, and he insisted I conic to his room and see the new camera his parents had sent him for his birthday. It had arrived yesterday, and with a light stand he showed me — a horizontal gas pipe on a stand, punctured for a dozen flames and backed by a reflector — he'd taken portraits of everyone in the house, and even photographed some of the rooms by daylight. He developed and printed his own films; there were a couple dozen of them strung out on a line like a washing, drying, and I saw that he'd printed them in circles, rectangles, ovals, and every other style, having a great time. I looked his camera over, a big affair weighing seven or eight pounds, I judged, holding and examining it. It was all polished wood, brass, glass, and red leather, wonderfully handsome. I told him so, said I was a camera bug, too, and he offered to lend it to me sometime, and I said I might take him up on it. Then he made me pose, and took my picture — a shorter exposure than I'd have thought, only a few seconds — and promised me a full set, too. I didn't particularly want them then, though I was glad to have them later. I left Felix washing more prints, and that night when I got back to my room I found a full set under my door; everyone's portrait including my own, plus some of the house.

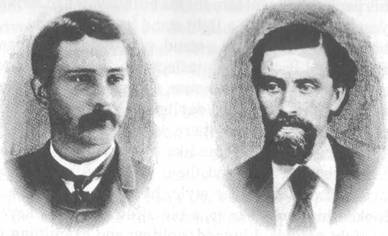

On the following page is one of them, Felix's own picture, and a good likeness except much more sober than I saw him; he was grinning and excited every moment I talked to him,

While I'm at it, I'll include the portrait he made of me: the one on the right. I'm not sure how good a likeness it is, but all in all I expect that's what I look like, beard and all; I never said I was handsome.

I left Felix, and went downstairs into the big front parlor that opened off the hall; a fire was moving behind the mica windows of a large black nickel-plated stove standing on a sheet of metal against one wall. Surmounting the stove stood a foot-high, nickel-plated knight in armor, and I walked over to look at it, reached out to touch it, and yanked my hand back; it was hot. Behind a pair of sliding doors I heard the clink of china and silver, and a murmur of voices. One was Julia's, I was sure, the other an older woman's. I imagined they were setting a table, and I coughed.

The doors rolled open, and Julia stepped in. She was wearing a maroon wool dress with white collar and cuffs, not the one Felix had photographed her in. This is his portrait of her, and tonight she wore her hair as you see it here, loosely arranged, covering the tops of her ears, and arranged at the back in a bun. Behind her I saw an oval table partly set; then a slim middle-aged woman stepped into the parlor after Julia.

Above right is Felix's portrait of her, and a very good one; this is just how she looked.

Julia said, "Aunt Ada, this is Simon Morley, who arrives without reference or much luggage. But with an abundance of soft sawder with which he is most generous. Mr. Morley, Madam Huff."

I didn't know what "soft sawder" was, but learned later that "soft solder" was the phrase and that it meant exaggerated speech or flattery or both. Smiling at what Julia had said, her aunt actually curtsied; I'd never seen it done before. "How do you do, Mr. Morley."

It seemed only natural, as though I'd done it always, to bow in response. "How do you do, Madam Huff. Miss Julia leaves me nothing to reply except that I'm happy to be here. This is a charming room." Listening to myself, I had to suck in my cheeks to keep my face straight.

"May I show it to you?" Aunt Ada gestured at the room, and I glanced around it with genuine interest. This is the view Felix took of part of the room with his birthday camera; it doesn't show all of it by any means. It was carpeted and wallpapered, and at the windows, in addition to white lace curtains, there were purple velvet drapes fringed with little balls. There were two large brocaded settees, two wood-and-black-leather rockers, three upholstered chairs, a desk, gilt-framed pictures on the walls.