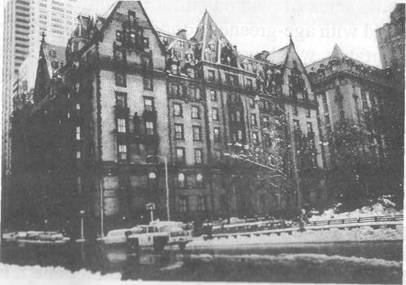

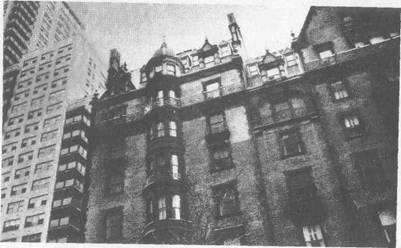

It's a wonderful sight, and the roof almost instantly pulled my eyes up; it was like a miniature town up there — of gables, turrets, pyramids, towers, peaks. From roof edge to highest peak it must have been forty feet tall; acres of slanted surfaces shingled in slate, trimmed with age-greened copper, and peppered with uncountable windows, dormer and flush; square, round, and rectangular; big and small; wide, and as narrow as archers' slits. As the shot that I took on the roof shows — at the bottom of the previous page — it rose into flagpoles and ornamental stone spires; it flattened out into promenades rimmed with lacy wrought-iron fences; and everywhere it sprouted huge fireplace chimneys. All I could do was turn to Rube, shaking my head and grinning with pleasure.

He was grinning, too, as proud as though he'd built the place. "That's the way they did things in the eighties, sonny! Some of those apartments have seventeen rooms, and I mean big ones; you can actually lose your way in an apartment like that. At least one of them includes a morning room, reception room, several kitchens, I don't know how many bathrooms, and a private ballroom. The walls are fifteen niches thick; the place is a fortress. Take your time, and look it over; it's worth it."

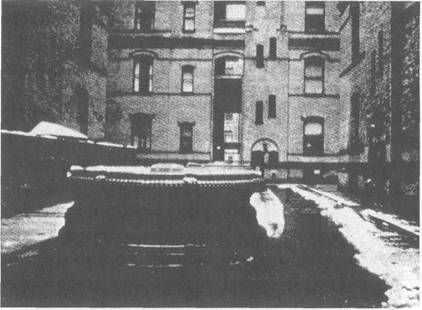

It was. I stood staring up at it, finding more things to be delighted with: handsome balconies of carved stone under some of the big old windows, a wrought-iron balcony running clear around the seventh story, rounded columns of bay windows rising up the building's side into rooftop cupolas. Rube said, "Plenty of light in those apartments: The building's a hollow square around a courtyard with a couple of spectacular big bronze fountains."

''Well, it's great, absolutely great." I was laughing, shaking my head helplessly, it was such a fine old place. "What is it, how come it's still there?"

"It's the Dakota. Built in the early eighties when this was practically out of town. People said it was so far from anything it might as well be in the Dakotas, so that's what it was called. That's the story, anyway. I know you won't be astonished to learn that a group of progress-minded citizens was all hot to tear it down a few years ago, and replace it with one more nice new modern monster of far more apartments in the same space, low ceilings, thin walls, no ballrooms or butler's pantries, but plenty of profit, you can damn well believe, for the owners. For once the tenants had money and could fight back; a good many rich celebrities live there. They got together, bought it, and now the Dakota seems safe. Unless it's condemned to make room for a crosstown freeway right through Central Park."

"Can we get in and look around?"

"We don't have time today."

I looked up at the building again. "Must get a great view of the park from this side."

"You sure do." Rube seemed uninterested suddenly, glancing at his watch, and we turned to walk back along West Drive. Presently we walked out of the park; ahead to the west I could see the immense warehouse again, and read the faded lettering just under its roofline: BEEKEY BROTHERS, MOVING STORAGE, 555-8811.

If I'd expected Danziger's office, as I think I did, to be luxurious and impressive, I was wrong. Just outside it the black-and-white plastic nameplate beside the door merely said E.E. DANZIGER, no title. Rube knocked, Danziger yelled to come in, Rube opened the door, gestured me in, and turned away, murmuring that he'd see me later. Seated behind his desk, Danziger was on the phone, and he gestured me to a chair beside the desk. I sat down — I'd left my hat and coat downstairs again — and looked around as well as I could without seeming too curious.

It was just an office, smaller than Rossoff's and a lot more bare. It looked unfinished really, the office of a man who had to have one but wasn't interested in it, and who spent most of his time outside it. The outer wall was simply the old brick of the warehouse covered by a long pleated drape which didn't extend quite far enough to cover it completely. There was a standard-brand carpet; a small hanging bookshelf on one wall; on another wall a photograph of a woman with her hair in a style of the thirties; on a third wall, a huge aerial photograph of Winfield, Vermont, this view different from the one I'd seen earlier. Danziger's desk was straight from the stock of an office-supplies store, and so were the two leather-padded metal chairs for visitors. On the floor in a corner stood a cardboard Duz carton filled to overflowing with a stack of mimeographed papers. On a table against the far wall something bulky lay covered by a rubberized sheet.

Danziger finished his phone conversation; it had been something or other about authorizing someone to sign vouchers. He opened his top desk drawer, took out a cigar, peeled off the cellophane, then cut the cigar exactly in half with a pair of big desk scissors, and offered one of the halves to me. I shook my head, and he put it back in the drawer, then put the other half in his mouth, unlighted. "You liked the Dakota," he said; it wasn't a question, but a statement of fact. I nodded, smiling, and Danziger smiled too. He said, "There are other essentially unchanged buildings in New York, some of them equally fine and a lot older, yet the Dakota is unique; you know why?" I shook my head. "Suppose you were to stand at a window of one of the upper apartments you just saw, and look down into the park; say at dawn when very often no cars are to be seen. All around you is a building unchanged from the day it was built, including the room you stand in and very possibly even the glass pane you look through. And this is what's unique in New York: Everything you see outside the window is also unchanged."

He was leaning over the desk top staring at me, motionless except for the half cigar which rolled slowly from one side of his mouth to the other. "Listen!" he said fiercely. "The real-estate firm that first managed the Dakota is still in business and we've microfilmed their early records. We know exactly when all the apartments facing the park have stood empty, and for how long." He sat back. "Picture one of those upper apartments standing empty for two months in the summer of 1894. As it did. Picture our arranging — as we are — to sublet that very apartment for those identical months during the coming summer. And now understand me. If Albert Einstein is right once again — as he is — then hard as it may be to comprehend, the summer of 1894 still exists. That silent empty apartment exists back in that summer precisely as it exists in the summer that is coming. Unaltered and unchanged, identical in each, and existing in each. I believe it may be possible this summer, just barely possible, you understand, for a man to walk out of that unchanged apartment and into that other summer." He sat back in his chair, his eyes on mine, the cigar bobbing slightly as he chewed it.

After a long moment I said, "Just like that?"

"Oh, no!" He shot forward again, leaning across the desk toward me. "Not just like that by a long shot," he said, and suddenly smiled at me. "The uncountable millions of invisible threads that exist in here, Si" — he touched his forehead — "would bind him to this summer, no matter how unaltered the apartment around him." He sat back in his chair, looking at me, still smiling a little. Then he said very softly and matter-of-factly, "But I would say this project began, Si, on the clay it occurred to me that just possibly there is a way to dissolve those threads."