‘We don’t use magic, lad,’ the Spook said, his voice hardly more than a whisper in the darkness. ‘The main tools of our trade are common sense, courage and the keeping of accurate records, so we can learn from the past. Above all, v?e don’t believe in prophecy. We don’t believe that the future is fixed. So if what your mother wrote comes true, then it’s because we make it come true. Do you understand?’

There was an edge of anger in his voice but I knew it wasn’t directed at me, so I just nodded into the darkness.

‘As for being your mother’s gift to the County, every single one of my apprentices was the seventh son of a seventh son. So don’t you start thinking you’re anything special. You’ve a lot of study and hard work ahead of you.

‘Family can be a nuisance,’ the Spook went on after a pause, his voice softer, the anger gone. ‘I’ve only got two brothers left now. One’s a locksmith and we get on all right, but the other one hasn’t spoken to me for well over forty years, though he still lives here in Horshaw.’

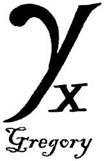

By the time we left the house, the storm had blown itself out and the moon was visible. As the Spook closed the front door, I noticed for the first time what had been carved there in the wood.

The Spook nodded towards it. ‘I use signs like this to warn others who’ve the skill to read them or sometimes just to jog my own memory. You’ll recognize the Greek letter gamma. It’s the sign for either a ghost or a ghast. The cross on the lower right is the Roman numeral for ten, which is the lowest grading of all. Anything after six is just a ghast. There’s nothing in that house that can harm you, not if you’re brave. Remember, the dark feeds on fear. Be brave and there’s nothing much a ghast can do.’

If only I’d known that to begin with!

‘Buck up, lad,’ said the Spook. ‘Your face is nearly down in your boots! Well, maybe this’ll cheer you up.’ He pulled the lump of yellow cheese out of his pocket, broke a small piece off and handed it to me. ‘Chew on this,’ he said, ‘but don’t swallow it all at once.’

I followed him down the cobbled street. The air was damp, but at least it wasn’t raining, and to the west the clouds looked like lamb’s wool against the sky and were starting to tear and break up into ragged strips.

We left the village and continued south. Right on its edge, where the cobbled street became a muddy lane, there was a small church. It looked neglected – there were slates missing off the roof and paint peeling from the main door. We’d hardly seen anyone since leaving the house but there was an old man standing in the doorway. His hair was white and it was lank, greasy and unkempt.

His dark clothes marked him out as a priest, but as we approached him, it was the expression on his face that really drew my attention. He was scowling at us, his face all twisted up. And then, dramatically, he made a huge sign of the cross, actually standing on tiptoe as he began it, stretching the forefinger of his right hand as high into the sky as he could. I’d seen priests make the sign before but never with such a big, exaggerated gesture, filled with so much anger. An anger that seemed directed towards us.

I supposed he’d some grievance against the Spook, or maybe against the work he did. I knew the trade made most people nervous but I’d never seen a reaction like that.

‘What was wrong with him?’ I asked, when we had passed him and were safely out of earshot.

‘Priests!’ snapped the Spook, the anger sharp in his voice. ‘They know everything but see nothing! And that one’s worse than most. That’s my other brother.’

I’d have liked to know more but had the sense not to question him further. It seemed to me that there was a lot to learn about the Spook and his past, but I had a feeling they were things he’d only tell me when he was good and ready.

So I just followed him south, carrying his heavy bag and thinking about what my mam had written in the letter. She was never one to boast or make wild statements. Mam only said what had to be said, so she’d meant every single word. Usually she just got on with things and did what was necessary. The Spook had told me there was nothing much could be done about ghasts, but Mam had once silenced the ghasts on Hangman’s Hill.

Being a seventh son of a seventh son was nothing that special in this line of work – you needed that just to be taken on as the Spook’s apprentice. But I knew there was something else that made me different. I was my mam’s son too.

Chapter Five

We were heading for what the Spook called his ‘Winter House’.

As we walked, the last of the morning clouds melted away and I suddenly realized that there was something different about the sun. Even in the County, the sun sometimes shines in winter, which is good because it usually means that at least it isn’t raining; but there’s a time in each new year when you suddenly notice its warmth for the first time. It’s just like the return of an old friend.

The Spook must have been thinking almost exactly the same thoughts because he suddenly halted in his tracks, looked at me sideways and gave me one of his rare smiles. ‘This is the first day of spring, lad,’ he said, ‘so we’ll go to Chipenden.’

It seemed an odd thing to say. Did he always go to Chipenden on the first day of the spring, and if so, why? So I asked him.

‘Summer quarters. We winter on the edge of Anglezarke Moor and spend the summer in Chipenden.’

‘I’ve never heard of Anglezarke. Where’s that?’ I asked.

‘To the far south of the County, lad. It’s the place where I was born. We lived there until my father moved us to Horshaw.’

Still, at least I’d heard of Chipenden so that made me feel better. It struck me that, as the Spook’s apprentice, I’d be doing a lot of travelling and would have to learn how to find my way about.

Without further delay we changed direction, heading north-east towards the distant hills. I didn’t ask any more questions, but that night, as we sheltered in a cold barn once more and supper was just a few more bites of the yellow cheese, my stomach began to think that my throat had been cut. I’d never been so hungry.

I wondered where we’d be staying in Chipenden and if we’d get something proper to eat there. I didn’t know anyone who’d ever been there but it was supposed to be a remote, unfriendly place somewhere up in the fells – the distant grey and purple hills that were just visible from my dad’s farm. They always looked to me like huge sleeping beasts, but that was probably the fault of one of my uncles, who used to tell me tales like that. At night, he said, they started to move, and by dawn whole villages had sometimes disappeared from the face of the earth, crushed into dust beneath their weight.

The next morning, dark grey clouds were covering the sun once more and it looked as if we’d wait some time to see the second day of spring. The wind was getting up as well, tugging at our clothes as we gradually began to climb and hurling birds all over the sky, the clouds racing each other east to hide the summits of the fells.

Our pace was slow and I was grateful for that because I’d developed a bad blister on each heel. So it was late in the day when we approached Chipenden, the light already beginning to fail.

By then, although it was still very windy, the sky had cleared and the purple fells were sharp against the skyline. The Spook hadn’t talked much on the journey but now he sounded almost excited as he called out the names of the fells one by one. There were names such as Parlick Pike, which was the nearest to Chipenden; others – some visible, some hidden and distant – were called Mellor Knoll, Saddle Fell and Wolf Fell.