DAVID B. COE

Seeds of Betrayal

Chapter One

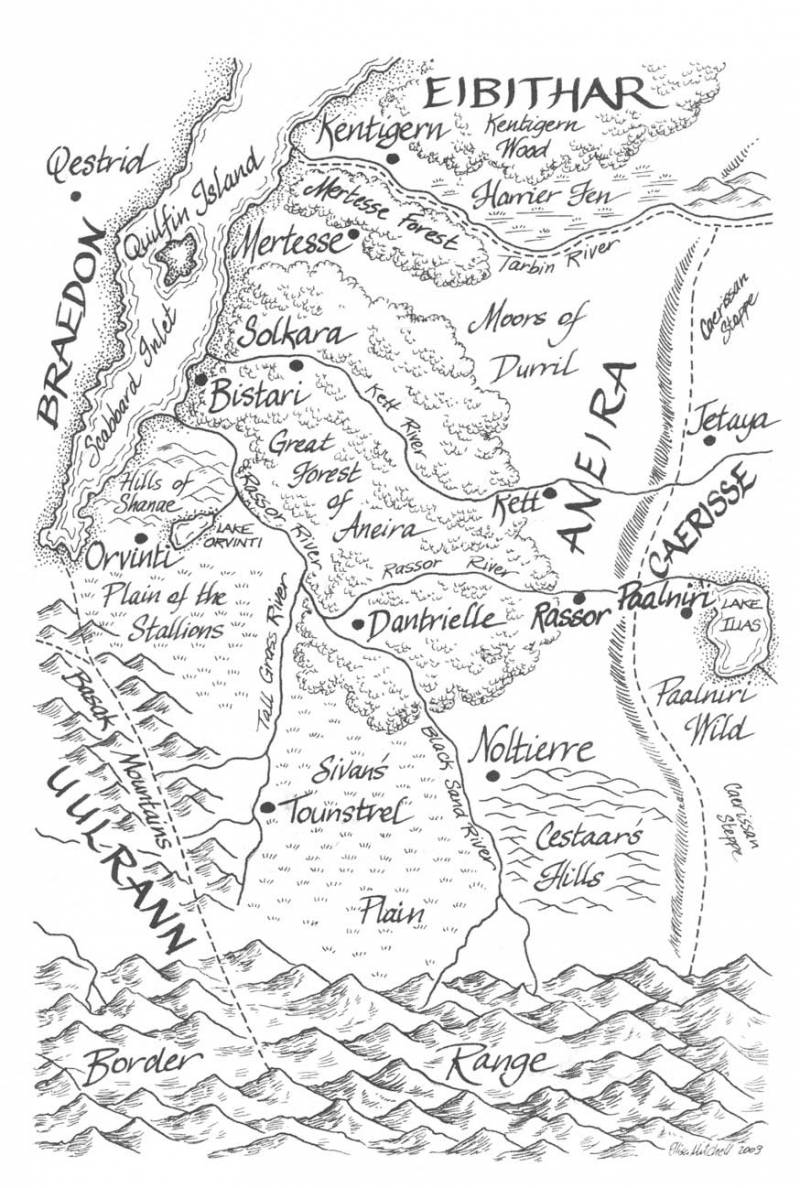

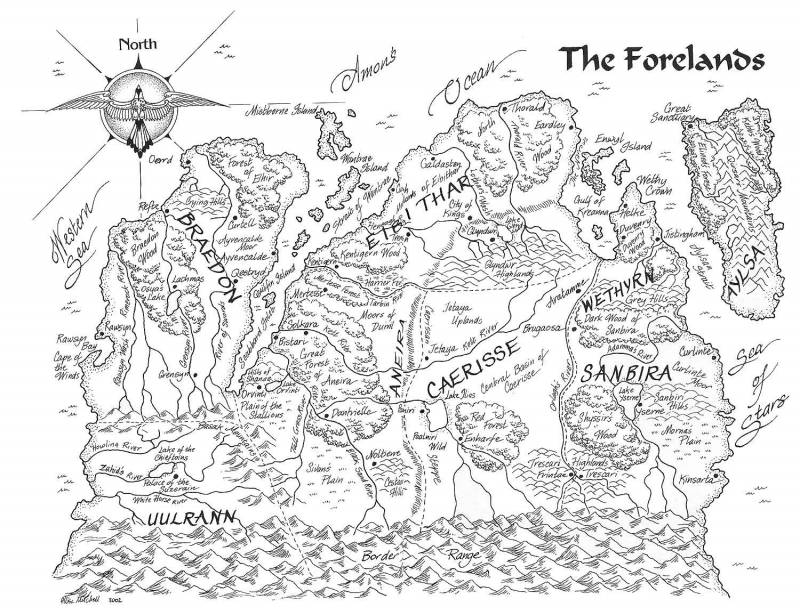

Bistari, Aneira, year 879, Bian’s Moon waning

The duke rode slowly among the trees, dry leaves crackling like a winter blaze beneath the hooves of his Sanbiri bay. Massive grey trunks surrounded him, resembling some vast army sent forth from the Underrealm by the Deceiver, their bare, skeletal limbs reaching toward a leaden sky. A few leaves rustling in a cold wind still clung stubbornly to the twisting branches overhead. Most were as curled and brown as those that covered the path, but a few held fast to the brilliant gold that had colored the Great Forest only a half turn before.

Even here, nearly a league from Bistari, Chago could smell brine in the air and hear the faint cry of gulls riding another frigid gust of wind. He pulled his riding cloak tighter around his shoulders and rubbed his gloved hands together, trying to warm them. This was no day for a hunt. He almost considered returning to the warmth of his castle. He would have, had he not been waiting for his first minister to join him. This hunt had been Peshkal’s idea in the first place, and they were to meet here, on the western fringe of the Great Forest.

“A hunt will do you good, my lord,” the minister had told him that morning. “This matter with the king has been troubling you for too long.”

At first Chago dismissed the idea. He was awaiting word from the dukes of Noltierre, Kett, and Tounstrel, and he still had messages to compose to Dantrielle and Orvinti. But as the morning wore on with no messengers arriving, and his mind began to cloud once more with his rage at what Carden had done, he reconsidered.

Kebb’s Moon, the traditional turn for hunting, had come and gone, and the duke had not ridden forth into the wood even once. More than half of Bian’s Moon was now gone. Soon the snows would begin and Chago would have to put away his bow for another year. He had the cold turns to fight Carden on his wharfages and lightering fees. Today, he decided, pushing back from his worktable and the papers piled there, I’m going to hunt.

When Peshkal entered the duke’s quarters and found him testing the tension of his bow, he seemed genuinely pleased, so much so that the Qirsi even offered to accompany Chago.

“Thank you, Peshkal,” Chago said, grinning. “But I know how you feel about hunting. I’ll take my son.”

“Lord Silbron is riding today, my lord, with the master of arms and your stablemaster.”

“Of course. I’d forgotten.” The duke hesitated a moment, gazing toward the window. Moments before he hadn’t been sure whether or not to go, but having made up his mind to ride, he was reluctant now to abandon his plans. “Then I’ll hunt alone.”

Peshkal’s pale features turned grave and he shook his head. “That wouldn’t be wise, my lord. There have been reports from your guards of brigands in the wood. Let me come with you. I have business in the city, but I’ll meet you on the edge of the wood just after midday.” The Qirsi forced a smile. “It will be my pleasure.”

Still Chago hesitated. As white-hairs went, Peshkal was reasonably good company. But like so many of the Eandi, the duke found all men of the pale sorcerer race somewhat strange. If the object of this hunt was to calm him, riding with the first minister made little sense.

Then again, neither would it be wise for him to ride alone; he’d heard talk of the brigands as well. In the end, Chago agreed to meet Peshkal in the wood, and a short time later, he rode forth from his castle, following the king’s road away from the dark roiling waters of the Scabbard Inlet toward the ghostly grey of the forest. His bow, unstrung for now, hung from the back of his saddle along with a quiver of arrows. But even after he entered the wood, he saw little sign of game. Not long ago, the forest would have been teeming with boar and elk, but each year, as the cold settled over central Aneira, the herds moved southward and inland, away from the coastal winds. Chago would be fortunate just to see a stag this day; there was little chance he would get close enough to one to use his bow.

Again, the duke felt the anger rising in his chest, until he thought his heart would explode. He could hardly blame the king for a poor hunt, yet already he was counting this cold, grey, empty day among the long list of indignities he had suffered at the hands of Carden the Third.

He couldn’t say when it began. In truth, his own feud with the Solkaran king was but a continuation of a centuries-old conflict between House Solkara and House Bistari that dated back to the First Solkaran Supremacy and the civil war that ended it over seven centuries ago. During the next two hundred and fifty years, the Aneiran monarchy changed hands several times, ending with the Solkaran Restoration and the establishment of the Second Solkaran Supremacy, which persisted to this day. It was a period of constantly shifting alliances, all of them based on little more than expedience and cold calculation. But throughout, Aneira’s two most powerful houses, Solkara and Bistari, always remained adversaries.

In the centuries since, when circumstances demanded it, the two houses managed to put their enmity aside. During the many wars the kingdom waged against Eibithar, Aneira’s neighbor to the north, men of Bistari fought beside men of Solkara. But the wars ended and the crises passed, and always when they did, one essential truth persisted: Chago’s people and those of the royal house simply did not trust each other.

Of course, rivalries among houses of the court were common in Aneira, and, from all Chago had heard, in the other kingdoms of the Forelands as well. When one’s enemy was the king, however, the royal court could be a lonely place. Chago had friends throughout the kingdom. Bertin of Noltierre journeyed to the western shores each year and stayed with Chago and Ria. And though he hadn’t seen Ansis of Kett in a number of years, he still counted the young duke among his closest allies. In most matters of the kingdom he could expect to find himself in agreement not only with Bertin and Ansis, but also with the dukes of Tounstrel, Orvinti, and Dantrielle.

Unless he was at odds with the king.

It was not that the others were blind to Carden’s considerable faults, or that they agreed with every decree that came from Castle Solkara. But Solkaran rulers had made it clear over the centuries that those who opposed their word, especially those who sided with Bistari in doing so, would suffer for their impudence. Raised fees, restrictions on hunting, increases in the number of men levied for service in the king’s army-all were measures used by Aneiran kings to punish what they viewed as defiant behavior. And no house had borne more of this than Chago’s own.

It was a credit to his strength and that of his forebears that Bistari had retained its status as one of the great families of Aneira despite the abuses of the royal house. A lesser house would have crumbled long ago; Bistari had thrived, all the while taking pains to keep its rivalry with House Solkara rrom manifesting itself as anything that could be interpreted as an act of treason. Bistari’s dukes paid their fees, though they were far greater than those paid by any other house. They sent soldiers to the king’s generals, though their quotas were too high. They hunted the forest only when they were allowed, though their season was nearly a full turn shorter than that allowed in Dantrielle, Rassor, and Kett. Let the Solkaran kings play their foolish games. Bistari was the rock against the tide, the family blazon a great black stone standing against the onslaught of the sea. Chago’s people endured. And this made Carden’s most recent affront that much more galling.