'Not an impostor?'

'I was very young then,' said Alan. 'I knew too much, and it was all quiz-rubbish. Now I start learning, something deep and narrow. I want to specialise in Mediaeval.'

'Interesting. But will it equip you for the running of flour-mills?'

'We both eat bread now,' said Alan, 'but we don't care for it very much. No, somebody else can get on with Walters' Flour, the Flower of Flours. I rather fancy useless scholarship.'

'That's Findlater's Church,' said Hillier. 'Can you see it? This is a terrible place for rain.'

'Why did you come here to live?' asked Clara.

'It's the only place for a Catholic Englishman forced into exile. A Western capital, not too big. The sea. It produced great men. Tomorrow you must come with me to St Patrick's. Swift and Stella, you know. And with the Irish, this is another attraction, history is timeless. Friend and enemy are caught in a stone clinch. It looks very much like the embrace of lovers.'

'Neutral,' sneered Alan. 'It opted out of the modern age. Good God, look at that laundry van. It has a swastika on it, look. Can you imagine that anywhere else in the world?'

'We have to be careful about that word "neutral",' said Hillier. 'You don't need bomb-ruins to remind you of wars. The big war can be planned here as well as anywhere -1 mean the war of which the temporal wars are a mere copy.'

'Good and Evil you mean,' said Alan.

'Not quite. We need new terms. God and Notgod. Salvation and damnation of equal dignity, the two sides of the coin of ultimate reality. As for the evil, they have to be liquidated.'

'The neutrals,' said Alan. 'If we could get down to the real struggle we wouldn't need spies and cold wars and spheres of influence and the rest of the horrible nonsense. But the people who are engaged in these mock things are better than the filthy neutrals.'

'Theodorescu died,' said Hillier. 'In Istanbul.'

'Ah. Did you kill him?' It was a cool assassin's question, professional.

'In a way, yes. I made sure he died.'

'I seem to remember there was an Indian woman with him,' said Clara. 'Rather lovely. In his power, I should have thought.'

'I never saw her again. She had great gifts. She was a door into the other world. Does that sound stupid? It wasn't the world of God and Notgod. It was a model of ultimate reality, shorn of the big duality however. Castrated ultimate reality. In one way she purveyed good, that other neutral. But good is a neutral inanimate -music, the taste of an apple, sex.'

'Not an image of God, then?' said Alan.

'Knowing God means also knowing His opposite. You can't get away from the great opposition.'

'That's Manichee stuff, isn't it? I'm quite looking forward to doing Mediaeval.'

They had arrived at the Gresham Hotel. Some little girls were waiting in the rain with autograph-books. They weren't sure whether to accost Clara or not. 'This place,' said Hillier, 'is a terrible place for film-stars.' A porter with a big umbrella saw to the luggage. Alan and Clara went to the reception-desk. 'I'll see you in that lounge there,' Hillier said. 'Among the film-stars. We'll have a drink.'

'On me,' said Alan.

When they came down from their rooms they gaped. Hillier had had his raincoat and muffler taken to the cloakroom. He sat there smiling in a clerical collar. But, a gentleman, he rose for Clara. Clara said the right thing: 'So I can call you Father after all.'

'I don't get it,' frowned Alan. 'You spouting that Manichee stuff. Most unorthodox.'

'If we're going to save the world,' said Hillier, 'wTe shall have to use unorthodox doctrines as well as unorthodox methods. Don't you think we'd all rather see devil-worship than bland neutrality? What are we going to have to drink?' A waiter was hovering, as though for a priestly blessing. Alan gave the order and, when the gins came, signed the chit with the flourish of a flour prince. He said: 'My real bewilderment is in seeing you got up like that. I'm sure it's just another of your impostures.'

'What they call a late vocation,' said Hillier. 'I had to go to Rome for a kind of crash-course. But one of these days we'll meet again on a voyage, and I'll be a real impostor. Another typewriter technician or perhaps a condom manufacturer or a computer salesman. I think, though, I'll be travelling tourist. Otherwise, it'll just be like old times – sneaking into the Iron Curtain countries, spying, being subversive. But the war won't be cold any more. And it won't be just between East and West. It just happens that I have the languages of cold-war espionage.'

'Like the Jesuits in Elizabeth's time,' said Alan. 'Equivocation and all that.'

'But will you kill?' asked Clara too loudly. Some neighbour drinkers, solid Dubliners, looked shocked.

'There's a commandment about killing.' Hillier winked.

'Champagne cocktails,' said Alan with excitement. 'Let's have champagne cocktails now.'

'You a priest,' wondered Clara. Hillier knew what she was remembering. He said: 'The appointment isn't a retrospective one.'

'That's where you're wrong,' said Alan. 'I wasn't such a fool that time, after all. On the ship, I mean. I knew you were an impostor.'

'Samozvanyets,' translated Hillier. 'You remember the man on the tram that night in Yarylyuk?'

'The night I-' It was quiet assassin's pride.

'Yes. He knew as well. And yet everything's an imposture. The real war goes on in heaven.' He fell without warning into a sudden deep pit of depression. His bed would be cold and lonely that night. The times ahead would be even harder than the times achieved. He was ageing. Perhaps the neutrals were right. Perhaps there was nothing behind the cosmic imposture. But the very ferocity of the attack of doubt now began to convince him: doubt was frightened; doubt was bringing up its guns. Accidie. He was hungry. Alan, who could see through impostures, could also read his thoughts.

'We'll have a good dinner,' said Alan. 'On me. With champagne. And we can drink toasts.'

'Lovely,' said Clara.

'Amen,' said Father Hillier.

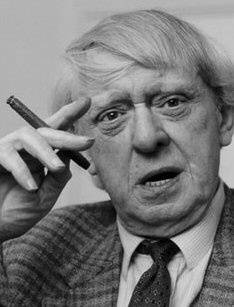

Anthony Burgess