Pick another bad memory. Run the movie however you usually do, to find out if it bothers you now- . . .

Now run that same memory backwards, from the end back to the beginning, just as if you were rewinding the film, and do it very quickly, in a few seconds. . . .

Now run the movie forward again. . . .

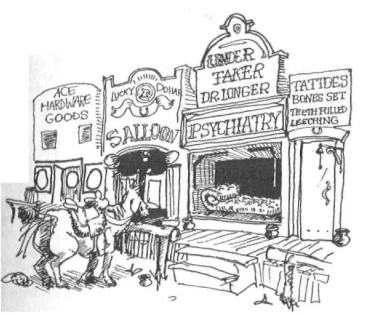

Do you feel the same about that memory after running it backwards? Definitely not. It's a little like saying a sentence backwards; the meaning changes. Try that on all your bad memories, and you'll save another thousand dollars worth of therapy. Believe me, when this stuff gets known, we're going to put traditional therapists out of business. They'll be out there with the people selling magic spells and powdered bat wings.

III. Points of View

People often say "You're not looking at it from my point of view," and sometimes they're literally correct. I'd like you to think of some argument you had with someone in which you were certain you were right. First just run a movie of that event the way you remember it. ...

Now I want you to run a movie of exactly the same event, but from the point of view of looking over that other person's shoulder, so that you can see yourself as that argument takes place. Go through the same movie from beginning to end, watching from this viewpoint. . . .

Did that make any difference? It may not change much for some of you, especially if you already do it naturally. But for some of you it can make a huge difference. Are you still sure you were right?

Man; As soon as I saw my face and heard my tone of voice, I thought, "Who'd pay any attention to what that turkey is saying!"

Woman: When I was on the receiving end of what I'd said, I noticed a lot of flaws in my arguments. I noticed when I was just running on adrenalin and wasn't making any sense at all. I'm going to go back and apologize to that person.

Man: I really heard the other person for the first time, and what she said actually made sense.

Man: As I listened to myself I kept thinking, "Can't you say it some other way, so that you can get your point across?"

How many of you are as certain about being right as you were before trying this different point of view? . . . About three out of 60. So much for your chances of being right when you're certain you are — about 5%.

People have been talking about "points of view" for centuries. However, they've always thought of it as being metaphorical, rather than literal. They didn't know how to give someone specific instructions to change his point of view. What you just did is only one possibility out of thousands. You can literally view something from any point in space. You can view that same argument from the side as a neutral observer, so that you can see yourself and that other person equally well. You can view it from somewhere on the ceiling to get "above it all," or from a point on the floor for a "worm's eye" view. You can even take the point of view of a very small child, or of a very old person. That's getting a little more metaphorical, and less specific, but if it changes your experience in a useful way, you can't argue with it.

When something bad happens, some people say, "Well, in a hundred years, who'll know the difference?" For some of you, hearing this doesn't have an impact. You may just think, "He doesn't understand." But when some people say it or hear it, it actually changes their experience and helps them cope with problems. So of course I asked some of them what they did inside their minds as they said that sentence. One guy looked down at the solar system from a point out in space, watching the planets spin around in their orbits. From that point of view, he could barely see himself and his problems as a tiny speck on the surface of the earth. Other people's pictures are often somewhat different, but they are similar in that they see their problems as a very small part of the picture, and at a great distance, and time is speeded up—a hundred years compressed into a brief movie.

All around the world people are doing these great things inside their brains, and they really work. Not only that; they're even announcing what they're doing. If you take the time to ask them a few questions, you can discover all sorts of things you can do with your brain.

There is another fascinating phrase that has always stuck in my mind. When you're going through something unpleasant, people will often say, "Later, when you look back at this, you'll be able to laugh." There must be something that you do in your head in the meantime that makes an unpleasant experience funny later. How many people in here have something you can look back on and laugh at? ... And do you all have a memory that you can't laugh at yet? . . . I want you to compare those two memories to find out how they're different. Do you see yourself in one, and not in the other? Is one a slide and one a movie? Is there a difference in color, size, brightness, or location? Find out what's different, and then try changing that unpleasant picture to make it like the one that you can already laugh at. If the one that you can laugh at is far away, make the other one far away too. If you see yourself in the one you laugh at, see yourself in the experience that is still unpleasant. My philosophy is: Why wait to feel better? Why not "look back and laugh" while you're going through it in the first place? If you go through something unpleasant, you would think that once is more than enough. But oh no, your brain doesn't think that. It says "Oh, you fouled up. I'll torture you for three or four years. Then maybe I'll let you laugh."

Man: I see myself in the memory I can laugh about; I'm an observer. But I feel stuck in the memory I still feel bad about, just like it's happening again.

That's a common response. Is that true for many of the rest of you? Being able to observe yourself gives you a chance to "review" an event "from a different perspective" and see it in a new way, as if it's happening to someone else. The best kind of humor involves looking at yourself in a new way. The only thing that prevents you from doing that with an event right away is not realizing that you can do it. When you get good at it, you can even do it while the event is actually happening.

Woman: What I do is different, but it works really well. I focus in like a microscope until all I can see is a small part of the event magnified, filling the whole screen. In this case all I could see was these enormous lips pulsating and jiggling and flopping as he talked. It was so grotesque I cracked up.

That's certainly a different point of view. And it's also something that you could easily try out when that bad experience is actually happening the first time.

Woman: I've done that, I'll be all stuck in some horrible situation and then I'll focus in on something and then laugh at how weird it is.

Now I want you all to think of two memories from your past: one pleasant and one unpleasant. Take a moment or two to re–experience those two memories in whatever way you naturally do. ...

Next, I want you to notice whether you were associated or dissociated in each of those memories.

Associated means going back and reliving the experience, seeing it from your own eyes. You see exactly what you saw when you were actually there. You may see your hands in front of you, but you can't see your face unless you're looking in a mirror.

Dissociated means looking at the memory image from any point of view other than from your own eyes. You might see it as if you were looking down from an airplane, or you might see it as if you were someone else watching a movie of yourself in that situation, etc.