Nevertheless, he decided to go on with it. It was not late, not even eleven o'clock yet, and the truth was that it could do no harm. The results of the third map bore no resemblance to the other two.

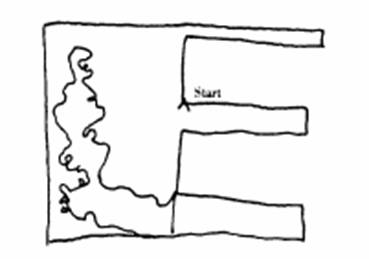

There no longer seemed to be a question about what was happening. If he discounted the squiggles from the park, Quinn felt certain that he was looking at the letter "E." Assuming the first diagram had in fact represented the letter "O," then it seemed legitimate to assume that the bird wings of the second formed the letter "W." Of course, the letters O-W-E spelled a word, but Quinn was not ready to draw any conclusions. He had not begun his inventory until the fifth day of Stillman's travels, and the identities of the first four letters were anyone's guess. He regretted not having started sooner, knowing now that the mystery of those four days was irretrievable. But perhaps he would be able to make up for the past by plunging forward. By coming to the end, perhaps he could intuit the beginning.

The next day's diagram seemed to yield a shape that resembled the letter "R." As with the others, it was complicated by numerous irregularities, approximations, and ornate embellishments in the park. Still clinging to a semblance of objectivity, Quinn tried to look at it as if he had not been anticipating a letter of the alphabet. He had to admit that nothing was sure: it could well have been meaningless. Perhaps he was looking for pictures in the clouds, as he had done as a small boy. And yet, the coincidence was too striking. If one map had resembled a letter, perhaps even two, he might have dismissed it as a quirk of chance. But four in a row was stretching it too far.

The next day gave him a lopsided "O," a doughnut crushed on one side with three or four jagged lines sticking out the other. Then came a tidy "F," with the customary rococo swirls to the side. After that there was a "B" that looked like two boxes haphazardly placed on top of one another, with packing excelsior brimming over the edges. Next there was a tottering "A" that somewhat resembled a ladder, with graded steps on each side. And finally there was a second "B": precariously tilted on a perverse single point, like an upside-down pyramid.

Quinn then copied out the letters in order: OWEROFBAB. After fiddling with them for a quarter of an hour, switching them around, pulling them apart, rearranging the sequence, he returned to the original order and wrote them out in the following.manner: OWER OF BAB. The solution seemed so grotesque that his nerve almost failed him. Making all due allowances for the fact that he had missed the first four days and that Stillman had not yet finished, the answer seemed inescapable: THE TOWER OF BABEL.

Quinn's thoughts momentarily flew off to the concluding pages of A. Gordon Pym and to the discovery of the strange hieroglyphs on the inner wall of the chasm-letters inscribed into the earth itself, as though they were trying to say something that could no longer be understood. But on second thought this did not seem apt. For Stillman had not left his message anywhere. True, he had created the letters by the movement of his steps, but they had not been written down. It was like drawing a picture in the air with your finger. The image vanishes as you are making it. There is no result, no trace to mark what you have done.

And yet, the pictures did exist-not in the streets where they had been drawn, but in Quinn's red notebook. He wondered if Stillman had sat down each night in his room and plotted his course for the following day or whether he had improvised as he had gone along. It was impossible to know. He also wondered what purpose this writing served in Stillman's mind. Was it merely some sort of note to himself, or was it intended as a message to others? At the very least, Quinn concluded, it meant that Stillman had not forgotten Henry Dark.

Quinn did not want to panic. In an effort to restrain himself, he tried to imagine things in the worst possible light. By seeing the worst, perhaps it would not be as bad as he thought. He broke it down as follows. First: Stillman was indeed plotting something against Peter. Response: that had been the premise in any case. Second: Stillman had known he would be followed, had known his movements would be recorded, had known his message would be deciphered. Response: that did not change the essential, factthat Peter had to be protected. Third: Stillman was far more dangerous than previously imagined. Response: that did not mean he could get away with it.

This helped somewhat. But the letters continued to horrify Quinn. The whole thing was so oblique, so fiendish in its circumlocutions, that he did not want to accept it. Then doubts came, as if on command, filling his head with mocking, sing-song voices. He had imagined the whole thing. The letters were not letters at all. He had seen them only because he had wanted to see them. And even if the diagrams did form letters, it was only a fluke. Stillman had nothing to do with it. It was all an accident, a hoax he had perpetrated on himself.

He decided to go to bed, slept fitfully, woke up, wrote in the red notebook for half an hour, went back to bed. His last thought before he went to sleep was that he probably had two more days, since Stillman had not yet completed his message. The last two letters remained-the "E" and the "L." Quinn's mind dispersed. He arrived in a neverland of fragments, a place of wordless things and thingless words. Then, struggling through his torpor one last time, he told himself that El was the ancient Hebrew for God.

In his dream, which he later forgot, he found himself in the town dump of his childhood, sifting through a mountain of rubbish.

9

THE first meeting with Stillman took place in Riverside Park. It was mid-afternoon, a Saturday of bicycles, dog-walkers, and children. Stillman was sitting alone on a bench, staring out at nothing in particular, the little red notebook on his lap. There was light everywhere, an immense light that seemed to radiate outward from each thing the eye caught hold of, and overhead, in the branches of the trees, a breeze continued to blow, shaking the leaves with a passionate hissing, a rising and failing that breathed on as steadily as surf.

Quinn had planned his moves carefully. Pretending not to notice Stillman, he sat down on the bench beside him, folded his arms across his chest, and stared out in the same direction as the old man. Neither of them spoke. By his later calculations, Quinn estimated that this went on for fifteen or twenty minutes. Then, without warning, he turned his head toward the old man and looked at him point-blank, stubbornly fixing his eyes on the wrinkled profile. Quinn concentrated all his strength in his eyes, as if they could begin to burn a hole in Stillman's skull. This stare went on for five minutes.

At last Stillman turned to him. In a surprisingly gentle tenor voice he said, "I'm sorry, but it won't be possible for me to talk to you. "

"I haven't said anything," said Quinn.

"That's true," said Stillman. "But you must understand that I'm not in the habit of talking to strangers."

"I repeat," said Quinn, "that I haven't said anything."

"Yes, I heard you the first time. But aren't you interested in knowing why?"

"I'm afraid not."

"Well put. I can see you're a man of sense."

Quinn shrugged, refusing to respond. His whole being now exuded indifference.

Stillman smiled brightly at this, leaned toward Quinn, and said in a conspiratorial voice, "I think we're going to get along."

"That remains to be seen," said Quinn after a long pause.

Stillman laughed-a brief, booming "haw”-and then continued. "It's not that I dislike strangers per se. It's just that I prefer not to speak to anyone who does not introduce himself. In order to begin, I must have a name."