In contrast to the dubious military strategy of the Mujahideen, that of the Afghans was simple and sound. To survive they had to hang on to Kabul and, if possible, the major population centres and military bases. Map 22 shows their strategic situation. To succeed in this they must concentrate their resources of men and munitions, and not be concerned if minor posts fell. They had to retain the ability to reinforce key positions by air if necessary, and above all they must keep Kabul supplied with food and military supplies. With logistic support the Soviets continued to be more than generous.

Although only a few advisers remained, Afghanistan was still the Soviets’ war, as Vietnam remained an American one even after they too had left their allies to fend for themselves. Vast infusions of money and materials arrived. The war was able to continue due to the massive in-place transfers of weapons and equipment as well as the huge re-supply effort. In 1988 over 1,000 armoured vehicles were handed over by the departing Soviets. It is estimated that the first six months of 1989 saw the transfer of $ 1.5 billion of military support to the Kabul regime, including 500 Scud surface-to-surface missiles. The Afghan Army still had tremendous superiority in what I call the three As—armour, artillery and aircraft. If they could bring these assets to the battle, if they could combine them effectively, then the Mujahideen would be defeated. The initiative was with the Mujahideen, hut they had to use it both strategically and tactically.

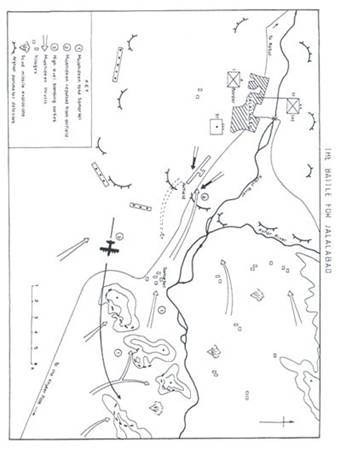

By March, 1989, the Mujahideen had assembled 5,()00-7,000 men in the hills around Jalalabad. However. their impending attack would not achieve surprise, as it had been heralded with too much publicity. The Jalalabad garrison knew what was coming and had made the necessary preparations. The 11th Division had been brought up to strength and other reinforcement units deployed in a ring of defences. Bunkers, barbed wire and extensive minefields surrounded Jalalabad. The outer defences extended 20 kilometres from the city, particularly to the east. Highway l, the link to Kabul, was protected by scores of posts throughout its length. Map 23 depicts the approximate layout of the Afghan defences and the main topographical features of tactical importance.

The Mujahideen assault began in early March with a direct, frontal attack from the east, up the Kabul river valley and on either side of Highway 1. Their first objective was the Samarkel position on the road 12 kilometres SE of Jalalabad. The ragtag warriors stormed ahead under cover of a heavy rocket, mortar and machine-gun barrage. Their initial impetus and enthusiasm carried them forward. The ridge east of Samarkel fell, and shortly afterwards the little village itself. Next the airfield, only 3 kilometres from the city, was taken by jubilant warriors yelling their war cries. This advance was led by several captured T-55 tanks crewed by the guerrillas. I believe this was the only tank versus tank engagement of the war. The Mujahideens’ success was short-lived, as the coordinated use of the three As drove them back from the strip.

The battle gradually became a stalemate, with more and more Mujahideen being sucked into the siege, but unable to coordinate their efforts, and wasting lives in reinforcing failure rather than success. Although some eight senior Commanders and their groups were deployed, there was no overall leader who could command obedience or devise a sound tactical plan. Attacks were invariably by day, with the Mujahideen walking or cycling forward in the early morning for a day’s shooting, and returning at dusk to sleep in the deserted villages in the surrounding rich farmland.

From the outset a steady stream of miserable refugees, old men, women and children, tramped towards Pakistan. By June 20,000 had gone. Meanwhile the siege of Jalalabad ground on with the Mujahideen unable to improve on their initial success. A decisive factor in the attackers’ failure was a lack of cooperation between the Commanders. They attacked when the mood took them, and without thought to concentrating or coordinating their efforts. As one exasperated Commander was quoted as saying in the London Sunday Times, ‘There is no coordination. If the Mujahideen attack on one side and keep the government busy, the Mujahideen on the other side are sleeping’. This lack of an overall plan led to many setbacks. The vital highway to Kabul, which, after the airport was closed, was virtually the only way of reinforcing or supplying Jalalabad, was seized by the guerrillas. But instead of closing the road permanently, the Mujahideen kept rotating the groups responsible which enabled the enemy to keep slipping convoys through.

All through April, May and June the position of the Mujahideen gradually worsened. Within a matter of a few weeks ammunition shortages became critical. The heavy, and at times wasteful, expenditure in the early days could not be made good. The US shipments were still substantially less than necessary, the reserve stocks had never been built up again after the Ojhri Camp disaster, and there had been little forward planning or dumping of available stocks prior to the battle. Not only was the strategic wisdom of attacking Jalalabad doubtful, but the tactics and logistics of carrying it out were quickly revealed as inadequate.

The Afghan resistance had also been underestimated. These soldiers had to fight to survive. Some early killings by the Mujahideen of prisoners confirmed in their minds that surrender was no answer. They were supported by enormous firepower; they had the advantage of being in strong defensive positions; numerically they equalled, if not outnumbered, their attackers, and their logistic needs were met. Aircraft, including Antonov-12 transports converted into bombers, flew up to twenty sorties a day. Heavy bombs, and cluster bombs that exploded above the ground scattering scores of bomblets over the target area, were used. These were extremely lethal against infantry. The effect on the ground is rather like the effect on a pond of throwing a fistful of gravel into the water, but over a far wider area. Although the Antonov is a slow-moving, propeller-driven aircraft, on these bombing missions it kept high, above the Stingers’ ceiling.

Then there was the psychological as well as the physical effect of the Scud missiles. At least three firing batteries of these missiles had been deployed at Kabul, where they were maintained and operated by Soviet personnel. They were new weapons, introduced to help compensate for the Soviet troop withdrawal, and they were technically complicated, which explained the Soviet crews. A battery consisted of three launcher vehicles, three re-loading vehicles each with one missile, a mobile meteorological unit, a tanker vehicle towing a pump unit on a trailer, and several command and control trucks. Getting ready to fire took an hour. It involved a lengthy survey procedure at the firing position, using theodolites and optical devices, being completed before the missile could be raised upright for launching.

The Scuds fired in Afghanistan carried high-explosive warheads weighing over 2,000 pounds. Jalalabad was comfortably within—range. The only warning the Mujahideen had was if they heard the sonic bang as the missile crashed through the sound barrier. They were area weapons. that is they could not achieve great accuracy. Their manuals indicate that when firing at a range such as from Kabul to Jalalabad, about half the missiles would fall in a circle with a radius of 900 metres. Over 400 Scud missiles thumped down among the hills around Jalalabad during the siege. I believe at least four fell inside Pakistan.

In four months of fighting the Mujahideen failed to take Jalalabad. It came as no surprise to me, or anybody else who took the trouble to study the situation. Their losses in men exceeded 3,000 killed and wounded. They expended what little reserves of ammunition had been accumulated, and their inability to breach the minefields and fixed defences boosted the morale of their enemies. The battle for Jalalabad renewed the Afghan Army’s confidence in its own ability, as well as telling the world that the Mujahideen were not yet able to march into Kabul. It was another major setback to the Jehad, from which the Mujahideen have not recovered to this day. Nor do I believe that their leadership has understood the lessons.