I did not realize it at the time but part of the problem was lack of communication between the US and Fundamentalist Leaders, who seldom travelled to the US, unlike the Moderates, such as Gailani and Mujaddadi, who went every six months or so—all expenses paid. The Americans, understandably, wanted to see how their money was being spent, they wanted to control things, to interfere; indeed, they felt they had a right to do so. This argument cut no ice with the Fundamentalists. They remained convinced that US help was entirely politically motivated, it was convenient for them pay for somebody else to take a crack crack at Soviets, and and get even for their humbling in Vietnam. As somebody who got to know senior officials on both sides of what became a serious controversy, I feel the Fundamentalists were correct in their assessment of American motives, but foolish to make their opinions so obvious, as without full US support the Jehad did not, and still cannot, succeed.

The Moderates are led by Molvi Nabi, Pir Gailani and Hazrat Mujaddadi. The first-named is a weak Leader, who leaves the running of Party affairs to his two sons, both of whom have been accused of retaining funds due to Commanders. The eldest son was involved in the Quetta incident mentioned earlier. Gailani is a soft-spoken, liberal democrat, fond of an easy life, who spends a considerable time abroad. He is not a forceful leader and seems to have little control over his Party bureaucracy. Mujaddadi is another linguist. He is also a prominent Islamic philosopher, whose main claim to fame was to serve four years in prison, three in solitary confinement, on charges of attempting to assassinate Nikita Khruschev during a visit to Kabul. He appears to be let down by his deputies and Party officials, over whom he seems to have little influence. Their dubious activities have now brought the Party into disrepute.

Another thing I learned during my first few months was that cooperation between Commanders in the field was not going to be achieved easily, even after the formation of the Alliance. Rivalries and petty jealousies between Commanders did not just go away because of the Alliance. In some ways it exacerbated the problem, as different Commanders from the same area would join different Parties, thus widening existing gaps between them. A Commander considered himself king in his area; he felt entitled to the support of the villages and to local taxes. He wanted the loot from attacking any nearby government post, and he wanted the heavy weapons to do it with, as they increased his chances of success and prestige, which in turn facilitated his recruiting a larger force. Such men often reacted violently to other commanders entering, passing through or ‘poaching’ on their territory. I could foresee serious difficulties in coordinating joint operations. No Party had a monopoly of power within specific areas or provinces in Afghanistan, although some might predominate. For example, in Paktia Province Hekmatyar, Khalis, Sayaf and Gailani all had Commanders operating, but only if they combined could any large-scale operation be effective.

Each Commander had his own base, usually in the remoter mountain valleys, within or near small village communities, from which he received reinforcements, food, shelter and sometimes money. As each of the 325 districts had at least one local base, the total in the whole jumbled network could have been up to 4000. But bases, vital though they were, are static, and the Mujahideen were reluctant to move away to operate against a more important target. For months at a time the Mujahideen in remote areas were not involved in any fighting, then perhaps came a sudden flare-up of violence. There seemed to be little planning, no discernible pattern to their activities; they fought when they saw an opportunity or they needed loot, and when the time suited them. I have summarized the political-military system of control and liaison for the period of my time with ISI on page 39. It looks neat and tidy as a diagram, but in practice it could get horribly confused.

I saw an example of this haphazard type of offensive around the small Afghan garrison towns of Urgun and Khost in the latter part of 1983. From August to November large numbers of Mujahideen attacked both towns, although Khost was not actually captured. When the government forces counter-attacked, just before the onset of winter, they opened up the road against little opposition. The Mujahideen around Khost preferred to move across to nearby Urgun in case it fell without their help, which would render them ineligible for any share of the loot. It was typical tribal fighting for immediate tangible gains, localized in area, and with no higher strategic objective.

Another critical factor that struck me about the war was that it would be a slow one. I could see that everything took time to decide, to discuss, to get moving. The Afghan is infinitely patient, there is seldom a rush, time is of little consequence to him. Things might get done, but slowly; normal military timetables were not going to work. I had no illusions that I could hurry them up. I was about to control a guerrilla army whose speed on the ground was measured in terms of how fast a man, or a horse, could walk across difficult terrain. The point was, however, that this gave them greater mobility than road-bound convoys or heavily armoured vehicles.

By the winter of 1984 (winter is from December until March) I had acquired, though personal contact, visits and briefings, some understanding of the military capabilities, weaknesses and potential of the Mujahideen I knew their command system through which I would have to work and I was confident that I could have meaningful discussions with General Akhtar and my staff, on how we might enhance their effectiveness as guerrillas.

Next, I turned to look at the enemy.

The Infidels

“It is right to be taught, even by an enemy. ”

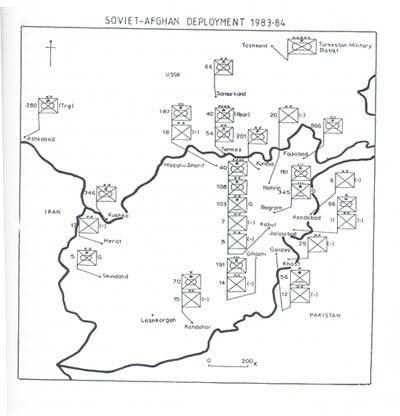

COURTESY of the CIA and their spy satellites over Afghanistan, my operations room walls were covered with excellent large-scale maps. They showed a rash of red symbols and pins. These portrayed the known locations of dozens of different formations and units, both ground and air, Soviet and Afghan. My first step in devising any plans to attack my enemy was to know where he was. Map 3 indicates, in outline, what I saw in terms of Soviet formations down to independent regimental, and Afghan to divisional, level. It was quite an imposing display. In all some 85,000 Soviet soldiers were inside Afghanistan, with another 30,000 or more deployed just north of the Amu River in the Soviet Union. Battalion-sized units from these latter formations frequently came over the river for operational duties, although the bulk had administrative or training responsibilities.

The Soviet chain of command went back to Moscow. There political decisions affecting the war were decided in the Kremlin. The Soviet General Staff (Operations Main Directorate) had initially appointed Marshal Sergei Sokolov to supervise the invasion. He had established his staff at the headquarters of the Southern Theatre of Operations. Further forward, at Tashkent, was the headquarters of the Turkestan Military District (TMD) with Colonel-General Yuri Maksimov in command. I was interested to learn that his performance as the overall Soviet commander of the Afghan War was highly regarded. In 1982 he had received promotion to colonel-general and was made a Hero of the Soviet Union at 58 two years earlier than usual. Under him was the 40th Army rear headquarters at Termez on the Afghanistan border. Its forward command elements were under Lieutenant-General V.M. Mikhailov at Tapa-Tajbeg camp, Kabul. His command had the rather cumbersome and misleading title of Limited Contingent of Soviet Forces in Afghanistan (LCSFA). Working alongside him, but with no troops under command, was the senior Soviet military adviser to the Afghan regime, Lieutenant-General Alexander Mayorov.