“It came all the way from Scritz on the cart,” said Shufti excitedly. She’d been working in the kitchen. It had become, now, her kitchen. “I wonder what it can be?” she said pointedly.

Polly levered the lid off the rough wooden crate, and found that it was full of straw with an envelope lying on top of it. She opened it.

Inside was an iconograph. It looked expensively done, a stiff family group with curtains and a potted palm in the background to give everything a bit of style. On the left was a middle-aged man looking proud; on the right was a woman of about the same age, looking rather puzzled but nevertheless pleased because her husband was happy; and here and there, staring at the viewer with variations of smile and squint, and expressions extending from interest to a sudden recollection that they should have gone to the toilet before posing, were children ranging from tall and gangly to small and smugly sweet.

And sitting on a chair in the middle, the focus of it all, was Sergeant-major Jackrum, shining like the sun.

Polly stared, and then turned the picture over. On the back was written, in big black letters: “SM Jackrum’s Last Stand!” and, underneath, “Don’t need these.”

She smiled, and pulled aside the straw. In the middle of the box, wrapped in cloth, were a couple of cutlasses.

“Is that old Jackrum?” said Shufti, picking up the picture.

“Yes. He’s found his son,” said Polly, unwinding a blade. Shufti shuddered when she saw it.

“Evil things,” she said.

“Things, anyway,” said Polly. She laid both the cutlasses on the table, and was about to lift the box out of the way when she saw something small in the straw at the bottom. It was oblong, and wrapped in thin leather.

It was a notebook, with a cheap binding and musty yellowing pages.

“What’s that?” said Shufti.

“I think it’s his address book,” said Polly, flicking through the pages.

This is it, she thought. It’s all here. Generals and majors and captains, oh my. There must be… hundreds. Maybe a thousand! Names, real names, promotions, dates… everything…

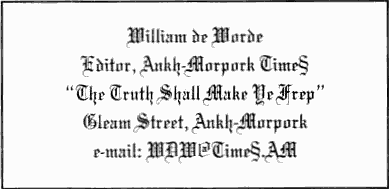

She pulled out a white pasteboard rectangle that had been inserted like a bookmark. It showed a rather florid coat of arms and bore the printed legend:

Someone had crossed out the “p” in “frep” and pencilled in an “e” above it.

It was a sudden strange fancy…

How many ways can you fight a war? Polly wondered. We have the clacks now. I know a man who writes things down. The world turns. Plucky little countries seeking self-determination… could be useful to big countries with plans of their own.

Time to grab the cheese.

Polly’s expression as she stared at the wall would have frightened a number of important people.

They would have been even more concerned at the fact that she spent the next several hours writing things down, because it occurred to Polly that General Froc had not got where she was today by being stupid, and therefore she could profit from following her example. She copied out the entire notebook, and sealed it in an old jam jar, which she hid in the roof of the stables. She wrote a few letters. And she got her uniform out of the wardrobe and inspected it critically.

The uniforms that had been made for them had a special, additional quality that could only be called… girlie. They had more braid, they were better tailored, and they had a long skirt with a bustle rather than trousers. The shakos had plumes, too.

Her tunic had a sergeant’s stripes. It had been a joke. A sergeant of women. The world had been turned upside down, after all.

They’d been mascots, good-luck charms… And, perhaps, on the march to PrinceMarmadukePiotreAlbertHansJosephBernhardtWilhelmsberg a joke was what everyone needed. But, maybe, when the world turns upside down, you can turn a joke upside down too. Thank you, Gummy, even though you didn’t know what it was you were teaching me. When they’re laughing at you, their guard is down. When their guard is down, you can kick them in the fracas.

She examined herself in the mirror. Her hair, now, was just long enough to be a nuisance without being long enough to be attractive, so she brushed it and left it at that. She put the uniform on, but with the skirt over her trousers, and tried to put aside the nagging feeling that she was dressing up as a woman.

There. She looked completely harmless. She looked slightly less harmless with both cutlasses and one of the horsebows on her back, especially if you knew that the inn’s dartboards now had deep holes in the bullseyes from all the practising.

She crept along the hall to the window that overlooked the inn yard. Paul was up a ladder, repainting the sign. Her father was steadying the ladder and calling out instructions in his normal way, which was to call out the instruction just a second or two after you’d already started doing it. And Shufti, although Polly was the only one in The Duchess who still called her that and knew why, was watching them, holding Jack. It made a lovely picture. For a moment, she wished she had a locket.

The Duchess was smaller than she’d thought. But if you had to protect it by standing in the doorway with a sword, you were too late. Caring for small things had to start with caring for big things, and maybe the world wasn’t big enough.

The note she left on her dressing table read: “Shufti, I hope you and Jack are happy here. Paul, you look after her. Dad, I’ve never taken any wages, but I need a horse. I’ll try to have it sent back. I love you all. If I don’t come back, burn this letter and look in the roof of the stables.”

She dropped out of the window, saddled up a horse in the stables, and let herself out of the back gate. She didn’t mount up until she was out of earshot, and then rode down to the river.

Spring was pouring through the country. Sap was rising. In the woods, a ton of timber was growing every minute. Everywhere, birds were singing.

There was a guard on the ferry. He eyed her nervously as she led the horse aboard, and then grinned. “’Morning, miss!” he said cheerfully.

Oh, well… time to start. Polly marched in front of the puzzled man.

“Are you trying to be smart?” she demanded, inches from his face.

“No, miss—”

“That’s ‘sergeant’, mister!” said Polly. “Let’s try again, shall we? I said, are you trying to be smart?”

“No, sergeant!”

Polly leaned until her nose was an inch from his. “Why not?”

The grin faded. This was not a soldier on the fast track to promotion. “Huh?” he managed.

“If you are not trying to be smart, mister, you’re happy to be stupid!” shouted Polly. “And I’m up to here with stupid, understand?”

“Yeah, but—”

“But what, soldier?”

“Yeah, but… well… but… nothing, sergeant,” said the soldier.

“That’s good.” Polly nodded at the ferrymen. “Time to go?” she suggested, but in the tones of an order.

“Couple of people just coming down the road, sergeant,” said one of them, a faster man with an uptake.

They waited. There were, in fact, three people. One of them was Maladicta, in full uniform.

Polly said nothing until the ferry was out in mid-stream. The vampire gave her the kind of smile only a vampire can give. It would have been sheepish, if sheep had different teeth.

“Thought I’d try again,” she said.

“We’ll find Blouse,” said Polly.

“He’s a major now,” said Maladicta. “And happy as a flea because they’ve named a kind of fingerless glove after him, I heard. What do we want him for?”

“He knows about the clacks. He knows about other ways war can be fought. And I know… people,” said Polly.

“Ah. Do you mean the ‘Upon my oath, I am not a lying man, but I know people’ kind of people?”

“Those were the kind of people I had in mind, yes.” The river slapped against the side of the ferry.