Nevada Barr

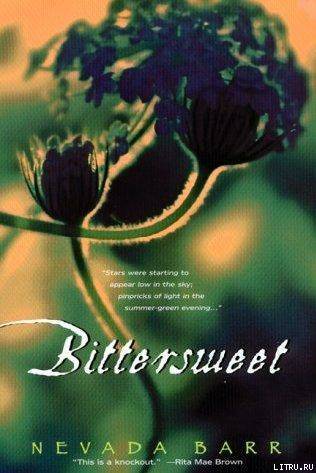

Bittersweet

© 1984

For Barns

1

A RAWBONED WOMAN NEARLY SIX FEET TALL PULLED ON THE BRASS handle; the door was wedged against the lintel and wouldn’t close-the fog that had lain over Philadelphia since late September had swelled the wood. Kicking a duffel bag out of the way, she grasped the knob with both hands and yanked. With a screech the door slammed shut. “Try opening that, Mr. Neff, you little, little man.” She turned the key and the bolt clicked home.

It was a brass key ornate with scrollwork; the initials AMG had been engraved on the lemon-shaped head. The woman ran her thumb over the worn letters. “Amanda Montgomery Grelznik,” she said softly and hurled the key over the porch railing into the fog. She listened for it to hit, but the thick mist swallowed the sound.

“Imogene.” An angular man, all in gray, stood at the gate watching her. His head was bare to the cold and his hands, knotted with arthritis, rested on the pickets of the fence like gnarled winter branches.

“Mr. Utterback!” She picked up her suitcases and came down the steps to meet him. “I didn’t hear you. With the fog I feel both deaf and blind.”

“I see thee are packed. I might have known thee’d be ready.”

“I sent most of my things ahead. The new owners, the Neffs, can have what is left.”

They looked back at the house in silence. It carried its age with dignity; the fine woodwork on the porch had been newly painted in summer and the yard was immaculate. “Mother and Father bought this house in 1842. I was born in that room nine months later to the day.” Imogene pointed to the gabled window above the porch. “Come April, I would have lived here thirty-one years.”

“I am sorry, Imogene.”

“No need, Mr. Utterback.” She laid her hand on his arm.

“I think thee might call me William.”

She laughed. “My tongue would cleave to the roof of my mouth.”

“Thou art the best teacher I have ever known,” he said simply. “I shall miss thee.”

Imogene’s narrow lower lip trembled; she pressed her fingers against it and coughed.

“Well.” He cleared his throat and looked away. He cleared it again. “Does thee have the letter?” She patted the leather duffel bag she had put on top of her suitcase. “Thee can read it. Joseph was a student of mine. I’ve told him of thy merit as a teacher and made no mention of the other.”

“Thank you.”

“Go on teaching, that is thanks enough.” He dug into the folds of his gray coat until his arm disappeared to the elbow, and pulled out a sheet of paper. “This came. I thought thee might like to read it. Isabelle Ann was a friend of thine.”

“Isabelle Ann Close?” Imogene came to his side to look over his arm.

“It’s Englewood now. She married a boy from Virginia and went west. This is all the way from Nevada Territory.” He shook out the letter and held it away from him in the manner of farsighted people. “She writes there are no qualified teachers there, and she asks after thee.” He handed Imogene the letter.

Imogene folded it up and put it into the pocket of her skirt. “I’ll read it on the train.” She looked at the little silver watch pinned to her coat. “I’d best be going.”

“Did thee leave the key for Mr. and Mrs. Neff?”

“I threw it away. It was Mother’s. There’s another on a nail just inside the back-porch door.”

“I wish he had offered a fair price, but he knew thee had to sell.” He smiled. “Thee really threw it away?” She nodded. “I’ll walk with thee to the train station.”

Imogene took up her suitcases abruptly. “No, please. I appreciate the offer, Mr. Utterback, but I’d rather go the last by myself. I have so much to look at on the way, I’m afraid I shouldn’t be very good company.” She set the suitcases down again and extended her hand. “Thank you again. I’ll write often.”

He took the hand and pressed it warmly. “Good-bye, Imogene. Give my regards to Joseph.” He preceded her out of the yard to hold the gate. “Thee are sure I cannot walk with thee?”

“Yes.” Her voice broke and she turned away.

The street was empty; people were closeted in their homes, with curtains drawn against the cold and fires lit against the damp. Windows showed yellow in the October afternoon. Imogene walked quickly down a footpath that was separated from the rutted street by a line of trees. Their branches vanished above her into the fog. Her breath came in clouds and beaded on the soft down of her upper lip.

The front door of the house on the corner opened as Imogene was passing, and a middle-aged woman muffled in a fur-lined cape emerged with a ten-year-old boy in tow. The child saw Imogene and snatched his hand free. He ran across the yard to where she walked by the fence.

“Miss Grelznik!”

Imogene stopped and smiled at him. “Where are you and your mother off to, Barton? You are dressed fit for a king’s coronation.”

He smeared his hands down over his dark wool suit, endangering all the buttons in their path. “We’re going to Uncle Herbert’s for dinner.”

“Barton Biggs!” Careful of her shoes, his mother picked her way over the frozen yard and clutched his arm. “Come away now.” She never gave Imogene a glance.

“Ma, Miss Grelznik asked-”

“Never mind.” She pulled at him until he let go of the fence and clumped along after her. He resisted, crying “Bye” over his shoulder, until she slapped his face.

Imogene watched them walk away. Her cheeks, already stung pink by the cold, deepened to scarlet and her hands shook when she picked up her bags. “Good-bye, Barton,” she called to his retreating form. “Take care.” Mother and son turned out of sight around the corner, and Imogene went on. A door slammed shut somewhere and she walked faster, keeping her eyes front.

A quarter of a mile brought her within sight of the train station-an imposing edifice with a cascade of shallow steps ending at a row of cabs parked in the street. A few of the drivers sat hunched on the seats, as dumb as their horses; the rest had crawled inside the cabs to await their fares in relative comfort. Imogene set her bags on the ground and rubbed her hands together. Her cotton gloves were the black of fall fashion, but too thin for warmth.

Several young men loitered at the top of the stairs. As Imogene threaded her way through the horse manure between the cabs, the eldest of the men-a slight fellow in his early thirties-pointed, calling the attention of the others to her, and said something. Imogene looked up when they laughed. He stepped out from the group and stood in front of her. “Just seeing you caught your train.” Imogene started to walk around him. He sidestepped and stopped her again. “Mary Beth ain’t here to see you off. I seen to that.” Imogene stepped to the right; he moved with her, blocking the way. Finally she looked at him, and though he stood on the step above her, they were eye-to-eye.

“As you said, Mr. Aiken, I have a train to catch. Be so good as to let me pass.”

He pushed his face near hers. “You stay clear of her.” His breath stank and Imogene stopped breathing.

“Don’t you go writing her none of your talk, neither.”

Imogene tightened her jaw until her lips and nostrils showed white against her windburned face. “Get out of my way.” She spat the words at him and he stumbled back.

“Darrel, come on.” His fellow loafers had grown uneasy.

Imogene pushed by him.

“Don’t even think about Mary Beth,” he yelled as the doors swung shut behind her.