Jean Marie Stine, Baroness Orczy, Anna Katherine Green, Arthur B. Reeve, C. L. Pirkis, Valentine, Edgar Jepson, Robert Eustace

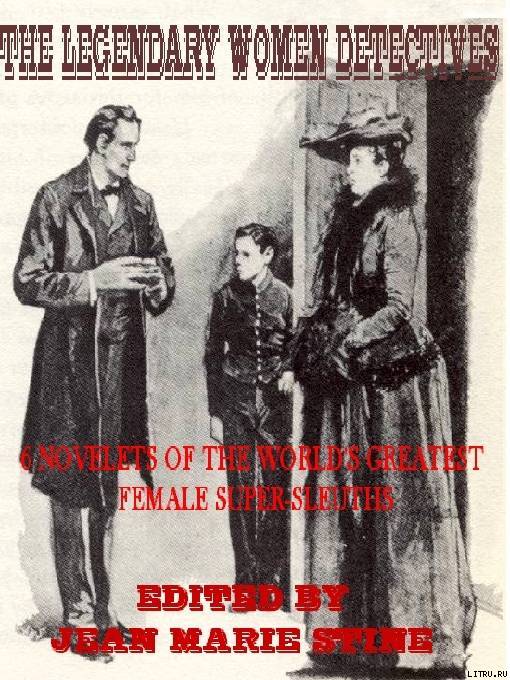

Legendary Women Detectives

SHERLOCK HOLMES' FEMALE RIVALS! This unique collection for connoisseurs of detection done female style brings back six of the greatest fictional women sleuths of the era of gaslights and horseless carriages. Fans of Kinsey Milhone and other contemporary women detectives, as well as of Agatha Christie and Honey West, will love this collection featuring the foremothers of today's fictional female crime-fighters. Long out of print and unobtainable, these celebrated women 'tecs -Baroness Orczy's Lady Molly of Scotland Yard, Anna Katharine Green's Violet Strange, Arthur B. Reeve's Constance Dunlap, C. L. Pirkis' Loveday Brooke, Valentine's Daphne Wrayne, and Edgar Jepson and Robert Eustace's Ruth Kelstern – were once nearly as famous as fictional sleuth of Baker Street himself. Their fame waned in the long decades of the 1930s through the '80s, when female sleuths took a backseat to Sam Spade, Nero Wolfe, and the like. But, they are back to baffle and thrill contemporary readers in The Legendary Women Detectives edited by Jean Marie Stine.

INTRODUCTION

In the mystery field, women have always led and men followed, ever since Anna Katherine Green penned one of the earliest detective stories, The Levenworth Case, in 1878 (nine years before Sherlock Holmes 1887 debut). Though men always stole their thunder – until recently, all the famous of detectivedom were of the male ilk, Sherlock Holmes, Perry Mason, Nero Wolf – the dames have always been right there, detecting along side the dicks (public and private), if overshadowed by them. Thank heaven all that has changed! Now many of the most popular, bestselling detective characters are female, and about time. When readers today are asked to name a famous fictional private eye, they are more likely to reply “Kinsey Milhone” or “V. I. Warshawski” than “Mathew Scudder” or even the ubiquitous “Spencer.”

Meanwhile, let us not neglect their nearly-forgotten foremothers and grandmothers in the celebrated cannons of fictional crime. In days of yore, when the great Sherlock still strode London’s foggy streets, Lady Molly, Violet Strange, Constance Dunlap, Ruth Kelstern, Solange Fontaine, Madame Storey, and a legion of their sisters in the detection of crime were on the trail, and like their masculine counterparts, they always got their man – and often with considerably more aplomb and adroitness. Later, in the 1930s and “40s, their successors, like Dol Bonner and Amy Brewster (available in PageTurner e-book editions), performed the honours with equal success and skill.

This collection resurrects six of the most memorable of the legendary women detectives, in six of their most memorable cases. Here is crime in the day of the Hansom cab, the horseless carriage, the gaslight and the sputtering new electric kind. You’ll find police detectives, private detectives, even scientific detectives among these turn-of-the last century female felon-catchers. You’ll also find hours of true mystery reading pleasure as well. Instead of the old cry in mysteries of “Find the woman!” this is strictly a case where the Women do the finding.

Jean Marie Stine

4/6/2003

THE MAN IN THE INVERNESSCAPE by Baroness Orczy

(Sleuth: Lady Molly)

Lady Molly is one of three great detectives created by the legendary author of the Scarlet Pimpernel novels. Her most famous mystery creation is undoubtedly the Old Man in the Corner (see The Legendary Detectives Vol. I-II.). But Lady Molly Robertson-Kirk runs him a close second and is one of the earliest and most intrepid of women detectives. Lady Molly joined Scotland Yard to prove the innocence of her husband, who had been framed for murder and languished in Dartmoor Prison, and to capture the real killer. Along the way she solved a number of cases which stumped the collective male force of the CID. Her investigations were collected as Lady Molly of Scotland Yard (1910).

Well, you know, some say she is the daughter of a duke, others that she was born in the gutter, and that the handle has been soldered onto her name in order to give her style and influence.

I could say a lot, of course, but “my lips are sealed,” as the poets say. All through her successful career at the Yard she honoured me with her friendship and confidence, but when she took me in partnership, as it were, she made me promise that I would never breathe a word of her private life, and this I swore on my Bible oath “wish I may die,” and all the rest of it.

Yes, we always called her “my lady,” from the moment that she was put at the head of our section; and the chief called her “Lady Molly” in our presence. We of the Female Department are dreadfully snubbed by the men, though don’t tell me that women have not ten times as much intuition as the blundering and sterner sex; my firm belief is that we shouldn’t have half so many undetected crimes if some of the so-called mysteries were put to the test of feminine investigation.

Many people say – people, too, mind you, who read their daily paper regularly – that it is quite impossible for any one to “disappear” within the confines of the British Isles. At the same time these wise people invariably admit one great exception to their otherwise unimpeachable theory, and that is the case of Mr. Leonard Marvell, who, as you know, walked out one afternoon from the Scotia Hotel in Cromwell Road and has never been seen or heard of since.

Information had originally been given to the police by Mr. Marvell’s sister Olive, a Scotchwoman of the usually accepted type: tall, bony, with sandy-coloured hair, and a somewhat melancholy expression in her blue-grey eyes.

Her brother, she said, had gone out on a rather foggy afternoon. I think it was the third of February, just about a year ago. His intention had been to go and consult a solicitor in the City-whose address had been given him recently by a friend – about some private business of his own.

Mr. Marvell had told his sister that he would get a train at South Kensington Station to Moorgate Street, and walk thence to Finsbury Square. She was to expect him home by dinnertime.

As he was, however, very irregular in his habits, being fond of spending his evenings at restaurants and music halls, the sister did not feel the least anxious when he did not return home at the appointed time. She had her dinner in the table d’hote room, and went to bed soon after ten.

She and her brother occupied two bedrooms and a sitting room on the second floor of the little private hotel. Miss Marvell, moreover, had a maid always with her, as she was somewhat of an invalid. This girl, Rosie Campbell, a nice-looking Scotch lassie, slept on the top floor.

It was only on the following morning, when Mr. Leonard did not put in an appearance at breakfast that Miss Marvell began to feel anxious. According to her own account, she sent Rosie in to see if anything was the matter, and the girl, wide-eyed and not a little frightened, came back with the news that Mr. Marvell was not in his room, and that his bed had not been slept in that night.

With characteristic Scottish reserve, Miss Olive said nothing about the matter at the time to any one, nor did she give information to the police until two days later, when she herself had exhausted every means in her power to discover her brother’s whereabouts.