I resisted for two days, three days, a week. I threw myself into other writing, went out on excursions all day and read a great deal. Such were the stratagems I employed to elude the invisible presence. But my mind was entirely absorbed by a powerful feeling of disquiet on Zorba's behalf.

One day I was seated on the terrace of my house by the sea. It was noon. The sun was very hot and I was gazing at the bare and graceful flanks of Salamis before me. Suddenly, urged on by that divine hand, I took some paper, stretched myself out on the burning flagstones of the terrace and began to relate the sayings and doings of Zorba.

I wrote impetuously, hastening to bring the past back to life, trying to recall Zorba and resuscitate him exactly as he was. I felt that if he disappeared it would be entirely my fault, and I worked day and night to draw as full a picture as possible of my old friend.

I worked like the sorcerers of the savage tribes of Àfrica when they draw on the walls of their caves the Ancestors they have seen in their dreams, striving to make it as lifelike as possible so that the spirit of the Ancestor can recognize his body and enter into it.

In a few weeks my chronicle of Zorba was complete. On the last day I was again sitting on the terrace in the late afternoon, and gazing at the sea. On my lap was the completely finished manuscript. I was happy and relieved, as though a burden had been lifted from me. I was like a woman holding her new-born baby.

Behind the mountains of the Peloponnesus the red sun was setting as Soula, a little peasant girl who brought me my mail from the town, came up to the terrace. She held a letter out to me and ran away… I understood. At least, it seemed to me that I understood, because when I opened the letter and read it, I did not leap up and utter a cry, I was not stricken with terror. I was sure. I knew that at this precise moment, while I was holding the manuscript on my lap and watching the setting sun, I would receive that letter.

Calmly, unhurriedly, I read the letter. It was from a village near to Skoplije in Serbia, and was written in indifferent German. I translated it:

I am the schoolmaster of this village and am writing to inform you of the sad news that Alexis Zorba, owner of a copper mine here, died last Sunday evening at six o'clock. On his deathbed, he called to me.

"Come here, schoolmaster," he said. "I have a friend in Greece. When I am dead write to him and tell him that right until the very last minute I was in full possession of my senses and was thinking of him. And tell him that whatever I have done, I have no regrets. Tell him I hope he is well and that it's about time he showed a bit of sense.

"Listen, just another minute. If some priest or other comes to take my confession and give me the sacrament, tell him to clear out, quick, and leave me his curse instead! I've done heaps and heaps of things in my life, but I still did not do enough. Men like me ought to live a thousand years. Good night!"

These were his last words. He then sat up in his bed, threw back the sheets and tried to get up. We ran to prevent him-Lyuba, his wife, and I, along with several sturdy neighbors. But he brushed us all roughly aside, jumped out of bed and went to the window. There, he grípped the frame, looked out far into the mountains, opened wide his eyes and began to laugh, then to whinny like a horse. It was thus, standing, with his nails dug into the window frame, that death came to him.

His wife Lyuba asked me to write to you and send her respects. The deceased often talked about you, she says, and left ínstructions that a santuri of his should be given to you after his death to help you to remember him.

The widow begs you, therefore, if you ever pass through our víllage, to be good enough to spend the night in her house as her guest, and when you leave in the morning, to take the santuri with you.

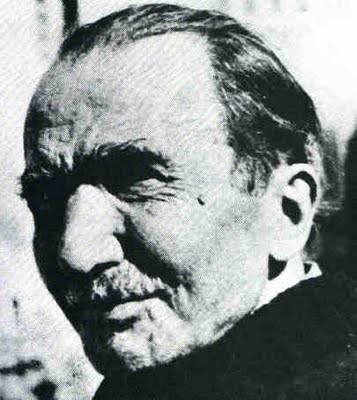

About The Author

Nikos Kazantzakis has been acclaimed by Albert Schweitzer, Thomas Mann, and critics and scholars in Europe and America as one of the most eminent and versatile writers of our time. He was born in Crete in 1883 and studied at the University of Athens, where he received his Doctor of Law degree. Later he studied in Paris under the philosopher Henri Bergson, and he completed his studies in literature and art during four other years in Germany and Italy. Before World War II he spent a great deal of his time on the island of Aegina, where he devoted himself to his philosophical and literary work. For a short while in 1945 he was Greek Minister of Education, and he was president of the Greek Society of Men of Letters. He spent most of the later years of his life in France. He died in Freïburg, Germany, in Octóber 1957.

He was the author of three novels which have been enthusiastically received in the United States and England: Zorba the Greek, The Greek Passion, and Freedom or Death. He was also a dramatist, translator, poet and travel writer. His crowning achievement, which he worked on over a period of twelve years, was The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel. In Kimon Friar's magnificent verse translation, this modern epic was published in the United States in 1958 and was acclaimed by critics and reviewers in such superlatives as "a masterpiece," "a stirring work of art," "a monument of the age," and "one of the outstanding literary events of our time."

Nikos Kazantzakis