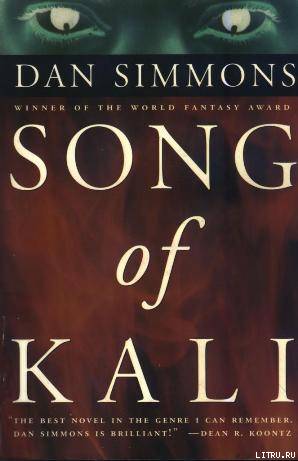

SONG OF KALI

by Dan Simmons

For HARLAN ELLISON, who has heard the song,

And for KAREN and JANE,

who are my other voices.

". . . there is a darkness. It

is for everyone . . . Only some Greeks

and admirers of theirs, in their

liquid noon, where the friendship

of beauty to human things was perfect,

thought they were clearly divided

from this darkness. And these

Greeks too were in it. But still

they are the admiration of the

rest of the mud-sprung, famine-

knifed, street-pounding, war-

rattled, difficult, painstaking,

kicked in the belly, grief and

cartilage mankind, the multitude,

some under a coal-sucking Vesuvius

of chaos smoke, some inside a

heaving Calcutta midnight, who

very well know where they are."

— Saul Bellow

"Why, this is Hell; nor am I

out of it."

— Christopher Marlowe

Some places are too evil to be allowed to exist. Some cities are too wicked to be suffered. Calcutta is such a place. Before Calcutta I would have laughed at such an idea. Before Calcutta I did not believe in evil — certainly not as a force separate from the actions of men. Before Calcutta I was a fool.

After the Romans had conquered the city of Carthage, they killed the men, sold the women and children into slavery, pulled down the great buildings, broke up the stones, burned the rubble, and salted the earth so that nothing would ever grow there again. That is not enough for Calcutta. Calcutta should be expunged.

Before Calcutta I took part in marches against nuclear weapons. Now I dream of nuclear mushroom clouds rising above a city. I see buildings melting into lakes of glass. I see paved streets flowing like rivers of lava and real rivers boiling away in great gouts of steam. I see human figures dancing like burning insects, like obscene praying mantises sputtering and bursting against a fiery red background of total destruction.

The city is Calcutta. The dreams are not unpleasant.

Some places are too evil to be allowed to exist.

Chapter One

"Today everything happens in Calcutta . . .

Who should I blame?"

— Sankha Ghosh

"Don't go, Bobby," said my friend. "It's not worth it."

It was June of 1977, and I had come down to New York from New Hampshire in order to finalize the details of the Calcutta trip with my editor at Harper's. Afterward I decided to drop in to see my friend Abe Bronstein. The modest uptown office building that housed our little literary magazine, Other Voices, looked less than impressive after several hours of looking down on Madison Avenue from the rarefied heights of the suites at Harper's.

Abe was in his cluttered office, alone, working on the autumn issue of Voices. The windows were open, but the air in the room was as stale and moist as the dead cigar that Abe was chewing on. "Don't go to Calcutta, Bobby," Abe said again. "Let someone else do it."

"Abe, it's all set," I said. "We're leaving next week." I hesitated a moment. "They're paying very well and covering all expenses," I added.

"Hnnn," said Abe. He shifted the cigar to the other side of his mouth and frowned at a stack of manuscripts in front of him. From looking at this sweaty, disheveled little man — more the picture of an overworked bookie than anything else — one would never have guessed that he edited one of the more respected "little magazines" in the country. In 1977, Other Voices hadn't eclipsed the old Kenyan Review or caused The Hudson Review undue worry about competition, but we were getting our quarterly issues out to subscribers; five stories that had first appeared in Voices had been chosen for the O'Henry Award anthologies; and Joyce Carol Gates had donated a story to our tenth-anniversary issue. At various times I had been Other Voices assistant editor, poetry editor, and unpaid proofreader. Now, after a year off to think and write in the New Hampshire hills and with a newly issued book of verse to my credit, I was merely a valued contributor. But I still thought of Voices as our magazine. And I still thought of Abe Bronstein as a close friend.

"Why the hell are they sending you, Bobby?" asked Abe. "Why doesn't Harper's send one of its big guns if this is so important that they're going to cover expenses?"

Abe had a point. Not many people had heard of Robert C. Luczak in 1977, despite the fact that Winter Spirits had received half a column of review in the Times. Still, I hoped that what people — especially the few hundred people who counted — had heard was promising. "Harper's thought of me because of that piece I did in Voices last year," I said. "You know, the one on Bengali poetry. You said I spent too much time on Rabindranath Tagore."

"Yeah, I remember," said Abe. "I'm surprised that those clowns at Harper's knew who Tagore was."

"Chet Morrow called me," I said. "He said that he had been impressed with the piece." I neglected to tell Abe that Morrow had forgotten Tagore's name,

"Chet Morrow?" grunted Abe. "Isn't he busy doing novelizations of TV series?"

"He's filling in as temporary assistant editor at Harper's," I said. "He wants the Calcutta article in by the October issue."

Abe shook his head. "What about Amrita and little Elizabeth Regina . . ."

"Victoria," I said. Abe knew the baby's name. When I had first told him the name we'd chosen for our daughter, Abe had suggested that it was a pretty damn Waspy title for the offspring of an Indian princess and a Chicago pollock. The man was the epitome of sensitivity. Abe, although well over fifty, still lived with his mother in Bronxville. He was totally absorbed in putting out Voices and seemed indifferent to anything or anyone that didn't directly apply to that end. One winter the heat had gone out in the office, and he had spent the better part of January here working in his wool coat before getting around to having it fixed. Most of Abe's interactions with people these days tended to be over the phone or through letters, but that didn't make the tone of his comments any less acerbic. I began to see why no one had taken my place as either assistant editor or poetry editor. "Her name's Victoria," I said again.

"Whatever. How does Amrita feel about you going off and deserting her and the kid? How old's the baby, anyway? Couple months?"

"Seven months old," I said.

"Lousy time to go off to India and leave them," said Abe.

"Amrita's going too," I said. "And Victoria. I convinced Morrow that Amrita could translate the Bengali for me." This was not quite the truth. It had been Morrow who suggested that Amrita go with me. In fact, it was probably Amrita's name that had gotten me the assignment. Harper's had contacted three authorities on Bengali literature, two of them Indian writers living in the States, before calling me. All three had turned down the assignment, but the last man they contacted had mentioned Amrita — despite her field being mathematics, not writing — and Morrow had followed up on it. "She does speak Bengali, doesn't she?" Morrow had asked over the phone. "Sure," I'd said. Actually, Amita spoke Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, and a little Punjabi as well as German, Russian, and English, but not Bengali. Close enough, I'd thought.

"Amrita wants to go?" asked Abe.