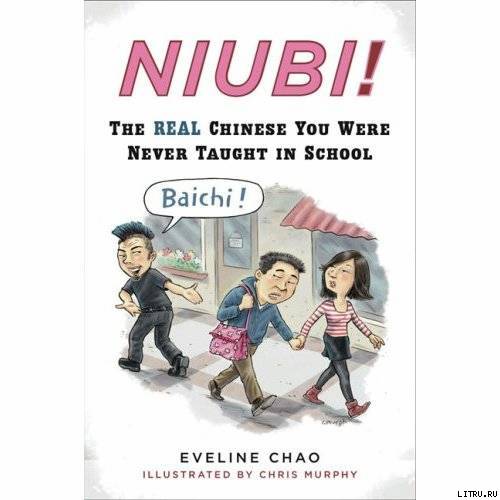

Eveline Chao

Niubi! The Real Chinese You Were Never Taught in School

Copyright © Eveline Chao, 2009

Illustrations by Chris Murphy

Acknowledgments

Endless thanks first and foremost to Maya Rock for making it all happen. I am also grateful to my agent Al Zuckerman at Writers House and my editor Nadia Kashper at Plume. Chris Murphy deserves special mention for his wonderful illustrations. And finally, thanks to Lu Bin, Amani Zhang, Wang Bin, Rachel Zhu, Emilio Liu, Lisa Hsia, Sam Zhao of les+ magazine, and Cecilia Hu, Gissing Liu, and Vivid Zhu for their advice and help on this project.

Introduction

On my first day in Beijing, my roommate and old college friend Ann sent me off to IKEA with three of her best Chinese friends. They picked me up in a red Volkswagen Santana and passed around a joint, blasting the Cure and Sonic Youth the whole ride there. In the crowded cafeteria at IKEA, we ate Swedish meatballs, french fries, and kung pao chicken, and then skated around the store with our shopping carts, stepping over the snoring husbands, asleep on the display couches, and smiling at the peasant families taking family photos in the living room sets. I bought bedding and some things for the kitchen, Da Li got a couple of plants, and Wang Xin bought a lamp. Traffic was bad on the ride home; we were navigating through a snarl at an intersection when yet another car cut us off. Lu Bin stuck his head out the window and bellowed “傻屄!” “Shǎbī!” (shah bee), or “fucking cunt,” at the other driver, then placidly turned down the music and, looking back, asked if I was a fan of Nabokov-he’d read Lolita in the Chinese translation and it was his favorite book.

For the next few months, I was too terrified to leave the apartment by myself and go make other friends, having not yet fully absorbed the fact that I’d left behind four years of life and a career in New York City and suddenly moved to this new and crazy place. So with a few exceptions, those three boys and my roommate were the only people I hung out with. Da Li owned an Italian restaurant, of all things, and we’d often meet there late in the evening and eat crème brûlée or drink red wine or consume whatever else we could beg off of him for free, and then pile into his and Lu Bin’s cars and head out on whatever adventure they had in mind. One night some big DJ from London was in town, spinning at a multilevel megaclub filled with nouveau riche Chinese. I bounced around on the metal trampoline dance floor and learned that the big club drink in China is whiskey with sweet green tea. Another night we headed to a smoke-filled dive to see a jazz band. The keyboardist had gone to high school with Lu Bin in Beijing, studied jazz in New York, and now sometimes performed with Cui Jian, a rock performer whose music, now banned from state radio, served as an unofficial anthem for the democracy movement during the late 1980s. My friends had a party promoter friend-a tiny, innocuous-seeming girl-who somehow got us into everything for free and would always turn and grin after rocking out to a set by a death-metal band from Finland, or a local hip-hop crew, and shout out, “太牛屄!” “Tài niúbī!” (tie nyoo bee), or “That was fucking awesome!” Other nights the boys would want to drive all the way to the Korean part of town, just to try out some Korean BBQ joint they’d heard about. And some nights we’d just drive around aimlessly and 岔 chă (chah), Beijing slang for “shoot the shit,” about music or art. Then we’d go back to Lu Bin’s to drink beer and watch DVDs (pirated, of course).

Most nights ended with deciding to get food at four in the morning and driving to Ghost Street, an all-night strip of restaurants lit up with red lanterns. There was one hot pot restaurant in particular that they liked, where, I remember, one night a screaming match broke out between two drunk girls at a table near ours. It concluded with one girl jumping up and shouting, “操你妈!” “Cào nǐ mā!” (tsow nee ma), or “Fuck you!” before storming out the door. The bleary-looking man left behind tried to console the other bawling girl, assuring her, “没事,她喝醉了” “Méishì, tā hēzuì le” (may shih, tah huh dzway luh): “Don’t worry about it-she was totally wasted.”

Intermittently, some new girl, whom one of the boys had recently decided was the love of his life, would appear in the group. There was a comic period when Da Li, who couldn’t speak any English, was 收 shōu (show), or screwing, a tall blonde who couldn’t speak any Chinese. Whenever they came out, one of us would inevitably get roped into playing translator in the long lead-up to the moment when they would finally leave us to go back to his place. You’d always get stuck repeating, over and over, some trivial thing that one had said to the other, and which the other was fixating on, thinking something important had been said. “What’d she say again?” Da Li would shout over the noise of the bar. “酷” “Kù” (coo), I’d yell back: “cool” in Chinese.

After a couple of years here, I’ve started taking Beijing for granted, and it’s harder for me to conjure up the same sense of magic and wonderment I felt at every little detail during those first few months. But then I’ll go back home, for a visit, to the United States and be reminded by the questions I’m asked of what a dark and mysterious abstraction China remains for most of the world. “Does everyone ride bicycles?” “Are there drugs in China?” “What are Chinese curse words like?” “Is there a hook-up scene? What’s dating like in China?” “What’s it like to be gay in China? Is it awful?” “How do you type Chinese on a computer? Are the keyboards different?” “How do Chinese URLs work?” One guy even asked, in gape-jawed amazement, if outsiders were allowed into the country.

Every time I hear these questions, I think back to those three boys who so strongly shaped my first impressions of China and wish that everyone could share the experiences I had-experiences that were neither “Western,” as half the people I talk to seem to expect, nor “Chinese,” as the other half expects, but rather their own unique thing. And then I remember the way those boys and their friends spoke-the casual banter, the familiar tone, the many allusions to both Western pop culture and ancient Chinese history; the mockery, the cursing, the lazy stoner talk, the dirty jokes, the arguments, the cynicism, the gossip and conjectures and sex talk about who was banging whom, but most of the time just the utterly banal chatter of everyday life-and I realize that one of the best ways to understand the true realities of a culture, in all its ordinariness and remarkableness, is to know the slang and new expressions and everyday speech being said on the street.

Hopefully, then, with the words in this book, some of those questions will be answered. Are there drugs in China? There are indeed drugs and stoners and cokeheads and all the rest in China, and, contrary to popular belief, lighting up a joint doesn’t instantly result in some sort of trapdoor opening in the sky and an iron-fisted authoritarian force descending from above to execute you on the spot. There’s even a massive heroin problem in the country, discussed in chapter 7. What about the gay scene? There is one and it’s surprisingly open, at least in the biggest cities. And I hope that after reading through the sex terms in chapter 5, the prostitution terminology in chapter 7, and the abundance of terms relating to extramarital affairs in chapter 4, we can put an end to those “exposés” about sex in China that are always appearing in the Western media, predicated on an outdated assumption that Chinese people somehow don’t have sex.