“Because on the day before we crossed the Somme,” Hook said, “the king hanged a man for theft.”

“The man stole from the church,” Swan said dismissively, “so of course he had to die.”

“But he never stole the box,” Hook said.

“He didn’t,” Tom Scarlet added.

“He never stole that box,” Hook said harshly, “yet the king hanged him. And hanging an innocent man is a sin. So why should God be on the side of a sinner? Tell me that, sir? Tell me why God would favor a king who murders an innocent man?”

There was another silence. The rain had eased a little and Hook could hear music coming from the French camp, then a burst of laughter. There had to be lamps inside the enemy’s tents because their canvas glowed yellow. The man called Swan shifted slightly, his plate leggings creaking. “If the man was innocent,” Swan said in a low voice, “then the king did wrong.”

“He was innocent,” Hook said stubbornly, “and I’d stake my life on that.” He paused, wondering if he dared go further, then decided to take the risk. “Hell, sir, I’d wager the king’s life on that!”

There was a hiss as the man called Swan took a sudden inward breath, but he said nothing.

“He was a good boy,” Will of the Dale said.

“And he never even got a trial!” Tom Scarlet said indignantly. “At home, sir, at least we get to say our piece at the manor court before they hang us!”

“Aye! We’re Englishmen,” Will of the Dale said, “and we have rights!”

“You know the man’s name?” Swan asked after a pause.

“Michael Hook,” Hook said.

“If he was innocent,” Swan said slowly, as if he were thinking about his response even as he spoke it, “then the king will have masses sung for his soul, he will endow a chantry for him, and he will pray himself every day for the soul of Michael Hook.”

Another sharp fork of lightning stabbed the earth and Hook saw the dark scar beside the king’s nose where a bodkin arrow had hit him at Shrewsbury. “He was innocent, sir,” Hook said, “and the priest who said otherwise lied. It was a family quarrel.”

“Then the masses will be sung, the chantry will be endowed, and Michael Hook will go to heaven with a king’s prayers,” the king promised, “and tomorrow, by God’s grace, we will fight those Frenchmen and teach them that God and Englishmen are not to be mocked. We will win. Here,” he thrust something at Hook, who took it and found it was a full leather bottle. “Wine,” the king said, “to warm you through the rest of the night.” He walked away, his armored feet squelching in the thick soil.

“He was a weird goddam fellow,” Geoffrey Horrocks said when the man called Swan was well out of earshot.

“I just hope he’s goddam right,” Tom Scarlet put in.

“Goddam rain,” Will of the Dale grumbled. “Sweet Jesus, I hate this goddam rain.”

“How can we win tomorrow?” Scarlet asked.

“You shoot well, Tom, and you hope God loves you,” Hook said, and he wished Saint Crispinian would break his silence, but the saint said nothing.

“If the goddamned French do get in among us tomorrow,” Tom Scarlet said, then faltered.

“What, Tom?” Hook asked.

“Nothing.”

“Say it!”

“I was going to say I’d kill you and you could kill me before they torture us, but that would be difficult, wouldn’t it? I mean you’d be dead and you’d find it really hard to kill me if you were dead.” Scarlet had sounded serious, but then began to laugh and suddenly they were all laughing helplessly, though none really knew why. Dead men laughing, but that, Hook thought, was better than weeping.

They shared the wine, which did nothing to warm them, and slowly, gray as mail, the dawn relieved the dark. Hook went into the eastern woods to empty his bowels and saw a small village just beyond the trees. French men-at-arms had quartered themselves in the hovels and now were mounting horses and riding toward the main encampment. Back on the plateau Hook watched the French forming their battles under their damp standards.

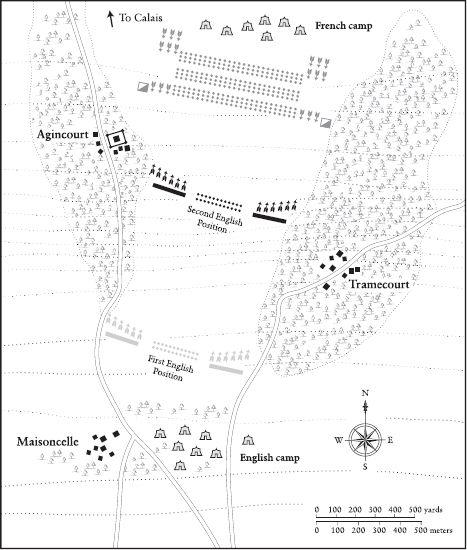

And the English did the same. Nine hundred men-at-arms and five thousand archers came to the field of Agincourt in the dawn, and across from them, across the furrows that had been deep plowed to receive the winter wheat, thirty thousand Frenchmen waited.

To do battle on Saint Crispin’s Day.

PART FOUR

Saint Crispin’s Day

ELEVEN

Dawn was cold and gray. A few spatters of rain blew fitfully across the plowed field, but Hook sensed the night’s downpours had ended. Small patches of mist clung to the furrows and lingered in the dripping trees.

The drummers behind the center of the English line were beating a quick rhythm that was punctuated by the flaring sound of trumpets. The musicians were massed where the king’s banner, the largest in the army, was flanked by the cross of Saint George, by the banner of Edward the Confessor, and by the flag of the Holy Trinity. That quartet of banners, all flown from extra-long poles, was in the middle of the center battle, while the flanking battles, the rearguard and vanguard, were similarly dominated by their leaders’ standards. There were at least fifty other flags flying in the damp air above Henry’s men-at-arms, but those English standards were as nothing to the array of silk and linen that was flaunted by the French. “Count the banners,” Thomas Evelgold had suggested as a way of estimating the French numbers, “and reckon every flag is a lord with twenty men.” Some French lords would have fewer men-at-arms and most would have far more, but Tom Evelgold was certain his method would yield an approximation of the enemy’s numbers, except that even Hook, with his good eyesight, could not distinguish the separate flags. There were simply too many. “There are thousands of the bastards,” Evelgold said unhappily, “and look at all those goddam crossbowmen!” The French archers were on the enemy’s flanks, but some way behind the leading men-at-arms.

“You wait!” an elderly man-at-arms, gray-haired and mounted on a mud-spattered gelding, shouted at the archers. He was just one of the numerous men who had come to offer advice or orders. “You wait,” he called again, “till I throw my baton in the air!” The man held up a short, thick staff that was wrapped in green cloth and surmounted by golden finials. “That’s the signal to shoot arrows! No one is to shoot before that! You watch for my baton!”

“Who’s that?” Hook asked Evelgold.

“Sir Thomas Erpingham.”

“Who’s he?”

“The man who throws the baton,” Evelgold said.

“I shall throw it high!” Sir Thomas shouted, “like this!” He threw the baton vigorously so that it circled high in the rain above him. He lunged to catch it as it fell, but missed. Hook wondered if that was a bad omen.

“Fetch it, Horrocks,” Evelgold said, “and look lively, lad!” Horrocks could not run, the furrows and ridges were too thick with mud and so his feet sank up to his ankles, but he retrieved the green stick and held it to the gray-haired knight. Sir Thomas thanked him, then moved down the line of archers to shout his orders again. Hook noticed how Sir Thomas’s horse struggled in the plowed land. “They must have set the share deep,” Evelgold said.

“Winter wheat,” Hook said.

“What’s that got to do with it?”

“Always plow deeper for winter wheat,” Hook explained.

“I never had to plow,” Evelgold said. He had been a tanner before he was appointed as a ventenar to Sir John.

“Plow deep in autumn and shallow in spring,” Hook said.

“I suppose it’ll save the bastards from digging us graves,” Evelgold said dourly, “they can just roll us into those big furrows and kick the soil over us.”

“Sky’s clearing,” Hook said. Off to the west, above the ramparts of the small castle of Agincourt that just showed above the woodland, the light was brightening.