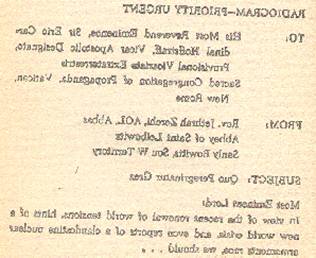

“Priority Urgent: To His Most Reverend Eminence, Sir Eric Cardinal Hoffstraff, Vicar Apostolic Designate, Provisional Vicariate Extraterrestris, Sacred Congregation of Propaganda, Vatican, New Rome…

“Most Eminent Lord: In view of the recent renewal of world tensions, hints of a new international crisis, and even reports of a clandestine nuclear armaments race, we should be greatly honored if Your Eminence deems it prudent to counsel us concerning the present status of certain plans held in abeyance. I have reference to matters outlined in the Motu proprio of Pope Celestine the Eighth, of happy memory, given on the Feast of the Divine Overshadowing of the Holy Virgin, Anno Domini 3735, and beginning with the words—” he paused to look through the papers on his desk—”“Ab hac planeta nativitatis aliquos filios Ecclesiae usque ad planetas solium alienorum iam abisse et numquam redituros esse intelligimus.” Refer also to the confirming document of Anno Domini 3749, Quo peregrinatur grex, pastor secure, authorizing the purchase of an island, uh-certain vehicles. Lastly refer to Cam belli nunc remote, of the late Pope Paul, Anno Domini 3756, and the correspondence which followed between the Holy Father and my predecessor, culminating with an order transferring to us the task of holding the plan Quo peregrinatur in a state of, uh — suspended animation, but only so long as Your Eminence approves. Our state of readiness with respect to Quo peregrinatur has been maintained, and should it become desirable to execute the plan, we would need perhaps six weeks’ notice…”

While the abbot dictated, the Abominable Autoscribe did no more than record his voice and translate it into a phoneme code on tape. After he had finished speaking he switched the process selector to ANALYZE and pressed a button marked TEXT PROCESSING. The ready-lamp winked off. The machine began processing.

Meanwhile, Zerchi studied the documents before him.

A chime sounded. The ready-lamp winked on. The machine was silent. With only one nervous glance at the FACTORY ADJUSTMENT ONLY box, the abbot dosed his eyes and pressed the WRITE button.

Clatterty-chat-clatter-spatter-pip popperty-kak-fub-clotter, the automatic writer chattered away at what he hoped would be the text of the radiogram. He listened hopefully to the rhythm of the keys. That first clattery-chat-clatter-spatter-pip had sounded quite authoritative. He tried to hear the rhythms of Alleghenian speech in the sound of the typing, and after a time he decided that there was indeed a certain Allegheny lilt mixed into the rattle of the keys. He opened his eyes. Across the room, the robotic stenographer was briskly at work. He left his desk and went to watch it work. With utmost neatness, the Abominable Autoscribe was writing the Alleghenian equivalent of:

“Hey, Brother Pat!”

He turned off the machine in disgust. Holy Leibowitz! Did we labor for this? He could not see that it was any improvement over a carefully trimmed goose-quill and a pot of mulberry ink.

“Hey, Pat!”

There was no immediate response from the outer office, but after a few seconds a monk with a red beard opened the door, and, after glancing at the open cabinets, the littered floor, and the abbot’s expression, he had the gall to smile.

“What’s the matter, Magister meus? Don’t you like our modem technology?”

“Not particularly, no!” Zerchi snapped. “Hey, Pat!”

“He’s out, m’Lord.”

“Brother Joshua, can’t you fix this thing? Really.”

“Really? — No, I can’t.”

“I’ve got to send a radiogram.”

“That’s too bad, Father Abbot. Can’t do that either. They Just took our crystal and padlocked the shack.”

“They?”

“Zone Defense Interior. All private transmitters have been ordered off the air”

Zerchi wandered to his chair and sank into it. “A defense alert. Why?”

Joshua shrugged. “There’s talk about an ultimatum. That’s all I know, except what I hear from the radiation counters.”

“Still rising?”

“Still rising.”

“Call Spokane.”

By midafternoon the dusty wind had come. The wind came over the mesa and over the small city of Sanly Bowitts. It washed over the surrounding countryside, noisily through the tall corn in the irrigated fields, tearing streamers of blowing sand from the sterile ridges. It moaned about the stone walls of the ancient abbey and about the aluminum and glass walls of the modern additions to the abbey. It besmirched the reddening sun with the dirt of the land, and sent dust devils scurrying across the pavement of the six-lane highway that separated the ancient abbey from its modern additions,

On the side road which at one point flanked the highway and led from the monastery by way of a residential suburb into the city, an old beggar clad in burlap paused to listen to the wind. The wind brought the throb of practice rocketry explosively from the south. Ground-to-space interceptor missiles were being fired toward target orbits from a launching range far across the desert. The old man gazed at the faint red disk of the sun while he leaned on his staff and muttered to himself or to the sun, “Omens, omens—”

A group of children were playing in the weed-filled yard of a hovel just across the side road, their games proceeding under the mute but all-seeing auspices of a gnarled black woman who smoked a weed-filled pipe on the porch and offered an occasional word of solace or remonstrance to one or another tearful player who came as plaintiff before the grandmotherly court of her hovel porch.

One of the children soon noticed the old tramp who stood across the roadway, and presently a shout went up: “Lookit, lookit! It’s old Lazar! Auntie say, he be old Lazar, same one ‘ut the Lor’ Hesus raise up! Lookit! Lazar! Lazar!”

The children thronged to the broken fence. The old tramp regarded them grumpily for a moment, then wandered on along the road. A pebble skipped across the ground at his feet.

“Hey, Lazar…!”

“Auntie say, what the Lor’ Hesus raise up, it stay up! Lookit him! Ya! Still huntin’ for the Lor’ ‘ut raise him. Auntie say—”

Another rock skipped after the old man, but he did not look back. The old woman nodded sleepily. The children returned to their games. The dust storm thickened.

Across the highway from the ancient abbey, atop one of the new aluminum and glass buildings, a monk on the roof was sampling the wind. He sampled it with a suction device which ate the dusty air and blew the filtered wind to the intake of an air compressor on the floor below. The monk was no longer a youth, but not yet middle-aged. His short red beard seemed electrically charged, for it gathered pendant webs and streamers of dust; he scratched it irritably from time to time, and once he thrust his chin into the end of the suction hose; the result caused him to mutter explosively, then to cross himself.

The compressor’s motor coughed and died. The monk switched off the suction device, disconnected the blower hose and pulled the device across the roof to the elevator and into the cage. Drifts of dust had settled in the corners. He closed the gate and pressed the Down button.

In the laboratory on the uppermost floor, he glanced at the compressor’s gauge — it registered MAX NORM — he closed the door, removed his habit, shook the dust out of it, hung it on a peg, and went over it with the section device. Then, going to the deep sheet-steel sink at the end of the laboratory workbench; he turned on the cold water and let it rise to the 200 Jug mark. Thrusting his head into the water, he washed the mud from his beard and hair. The effect was pleasantly icy. Dripping and sputtering, he glanced at the door. The likelihood of visitors just now seemed small. He removed his underwear, climbed into the tank, and settled back with a shivery sigh.