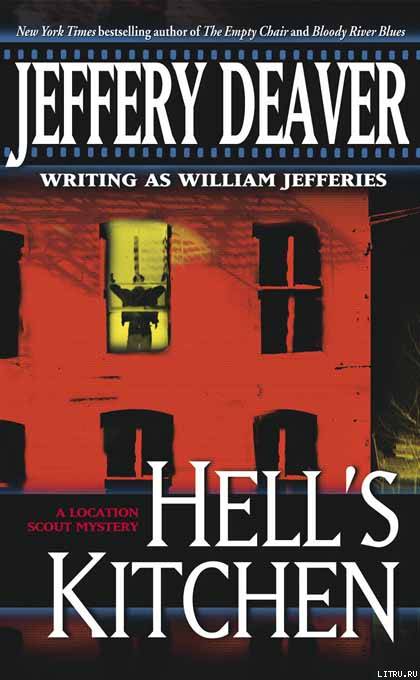

Jeffery Deaver

Hell's Kitchen

The third book in the John Pellam series, 2001

“I’m a professional. I’ve survived in a pretty rough business.”

– Humphrey Bogart

ONE

He climbed the stairs, his boots falling heavily on burgundy floral carpet and, where it was threadbare, on the scarred oak beneath.

The stairwell was unlit; in neighborhoods like this one the bulbs were stolen from the ceiling sockets and the emergency exit signs as soon as they were replaced.

John Pellam lifted his head, tried to place a curious smell. He couldn’t. Knew only that it left him feeling unsettled, edgy.

Second floor, the landing, starting up another flight.

This was maybe his tenth time to the old tenement but he was still finding details that had eluded him on prior visits. Tonight what caught his eye was a stained-glass valance depicting a hummingbird hovering over a yellow flower.

In a hundred-year-old tenement, in one of the roughest parts of New York City… Why beautiful stained glass? And why a hummingbird?

A shuffle of feet sounded above him and he glanced up. He’d thought he was alone. Something fell, soft thud. A sigh.

Like the undefinable smell, the sounds left him uneasy.

Pellam paused on the third-floor landing and looked at the stained glass above the door to apartment 3B. This valance – a bluebird, or jay, sitting on a branch – was as carefully done as the hummingbird downstairs. When he’d first come here, several months ago, he’d glanced at the scabby facade and expected that the interior would be decrepit. But he’d been wrong. It was a craftsman’s showpiece: oak floorboards joined solid as steel, walls of plaster seamless as marble, the sculpted newel posts and banisters, arched alcoves (built into the walls to hold, presumably, Catholic icons). He -

That smell again. Stronger now. His nostrils flared. Another thud above him. A gasp. He felt urgency and, looking up, he continued along the narrow stairs, listing against the weight of the Betacam, batteries and assorted videotaping effluence in the bag. He was sweating rivers. It was ten P.M. but the month was August and New York was at its most demonic.

What was that smell?

The scent flirted with his memory then vanished again, obscured by the aroma of frying onions, garlic and overused oil. He remembered that Ettie kept a Folgers coffee can filled with old grease on her stove. “Saves me some money, I’ll tell you.”

Halfway between the third and fourth floors Pellam paused again, wiped his stinging eyes. That’s what did it. He remembered:

A Studebaker.

He pictured his parent’s purple car, the late 1950s, resembling a spaceship, burning slowly down to the tires. His father had accidentally dropped a cigarette on the seat, igniting the upholstery of the Buck Rogers car. Pellam, his parents and the entire block watched the spectacle in horror or shock or secret delight.

What he smelled now was the same. Smoulder, smoke. Then a cloud of hot fumes wafted around him. He glanced over the banister into the stairwell. At first he saw nothing but darkness and haze; then, with a huge explosion, the door to the basement blew inward and flames like rocket exhaust filled the stairwell and the tiny first-floor lobby.

“Fire!” Pellam shouted, as the black cloud preceding the flames boiled up at him. He was banging on the nearest door. There was no answer. He started down the stairs but the fire drove him back, the tidal wave of smoke and sparks was too thick. He began to choke and felt a shudder through his body from the grimy air he was breathing. He gagged.

Goddamn, it was moving fast! Flames, chunks of paper, flares of sparks swirled up like a cyclone through the stairwell, all the way to the sixth – the top – floor.

He heard a scream above him and looked into the stairwell.

“Ettie!”

The elderly woman’s dark face looked over the railing from the fifth-floor landing, gazing in horror at the flames. She must’ve been the person he’d heard earlier, trudging up the stairs ahead of him. She held a plastic grocery bag in her hand. She dropped it. Three oranges rolled down the stairs past him and died in the flames, hissing and spitting blue sparks.

“John,” she called, “what’s…?” She coughed. “… the building.” He couldn’t make out any other words.

He started toward her but the fire had ignited the carpet and a pile of trash on the fourth floor. It flared in his face, the orange tentacles reaching for him, and he stumbled back down the stairs. A shred of burning wallpaper wafted upward, encircled his head. Before it did any damage it burned to cool ash. He stumbled back onto the third-floor landing, banged on another door.

“Ettie,” he shouted up into the stairwell. “Get to a fire escape! Get out!”

Down the hall a door opened cautiously and young Hispanic boy looked out, eyes wide, a yellow Power Ranger dangling in his hand.

“Call nine-one-one!” Pellam shouted. “Call!-”

The door slammed shut. Pellam knocked hard. He thought he heard screams but he wasn’t sure because the fire now sounded like a speeding truck, deafening roar. The flames ate up the carpet and were disintegrating the banister like cardboard.

“Ettie,” he shouted, choking on the smoke. He dropped to his knees.

“John! Save yourself. Get out. Run!”

The flames between them were growing. The wall, the flooring, the carpet. The valance exploded, raining hot shards of stained-glass birds on his face and shoulders.

How could it move so fast? Pellam wondered, growing faint. Sparks exploded around him, clicking and snapping like ricochets. There was no air. He couldn’t breathe.

“John, help me!” Ettie screamed. “It’s on that side. I can’t-” The wall of fire had encircled her. She couldn’t reach the window that opened onto the fire escape.

From the fourth floor down and the second floor up, the flames advanced on him. He looked up and saw Ettie, on the fifth floor, backing away from the sheet of flame that approached her. The portion of the stairs separating them collapsed. She was trapped two stories above him.

He was retching, batting at flecks of cinders burning holes in his work shirt and jeans. The wall exploded outward. A finger of flame shot out. The tip caught Pellam on the arm and set fire to the gray shirt.

He didn’t think so much about dying as he did the pain from fire. About it blinding him, burning his skin to black scar tissue, destroying his lungs.

He rolled on his arm and put the flame out, climbed to his feet. “Ettie!”

He looked up to see her turn away from the flames and fling open a window.

“Ettie,” he shouted. “Try to get up to the roof. They’ll get a hook and ladder…” He backed to the window, hesitated, then, with a crash, flung his canvas bag through the glass, the forty thousand dollars’ worth of video camera rolling onto the metal stairs. A half dozen other tenants, in panic, ignored it and continued stumbling downward toward the alley.

Pellam climbed onto the fire escape and looked back.

“Get to the roof!” he cried to Ettie.

But maybe that path too was blocked; the flames were everywhere now.

Or maybe in her panic she just didn’t think.

Through the boiling fire, his eyes met hers and she gave a faint smile. Then without a scream or shout that he could hear, Etta Wilkes Washington broke out a window long ago painted shut, and paused for a moment, looking down. Then she leapt into the air fifty feet above the cobblestoned alley beside the building, the alley that, Pellam recalled, contained the cobblestone on which Isaac B. Cleveland had scratched his declaration of love for teenage Ettie Wilkes fifty-five years ago. The old woman’s slight frame vanished into the smoke.