chapter twelve

Sigh out a lamentable tale of things,

Done long ago, and ill done

(John Ford, The Lover's Melancholy)

At ABout 7.15 (Johnson continued) on the sunny Tuesday morning of 9 July 1991, George Daley, of 2 Blenheim Villas, Begbroke, Oxon had taken his eight-year-old King Charles spaniel for an early-morning walk along the slip-road beside the Royal Sun, a road-side ale-house on the northern stretch of the A44, a mile or so on the Oxford side of Woodstock. At the bottom of a hawthorn hedge almost totally concealed by rank cow-parsley, Daley had spotted – as he claimed – a splash of bright colour; and as he ventured down, and near, he had all but trodden on a camera before seeing the scarlet rucksack.

Of course at this stage there had been no evidence of foul play – still wasn't – and it was the camera that had claimed most of Daley’s attention. He'd promised a camera to his son Philip, a lad just coming up for his sixteenth birthday; and the camera he'd found a heavy, aristocratic-looking thing, was a bit too much of a temptation. Both the rucksack and the camera he'd taken home, where cursorily that morning, in more detail later that evening, he and his wife Margaret had considered things.

‘Finders keepers', they'd been brought up to accept. And well, the rucksack clearly – and specifically – belonged to someone else, but the camera had no name on it, had it? For all they knew, it had no connection at all with the rucksack. So they'd taken out the film, which seemed to be fully used up anyway, and thrown it on the fire. Not a crime, was it? Sometimes even the police – Daley suggested – weren't all that sure what should be entered in the crime figures. If a bike got stolen, it was a crime all right. But if the owner could be persuaded that the bike hadn't really been stolen at all -just inadvertently 'lost', say – then it didn't count as a crime at all, now did it?

'Was he an ex-copper, this fellow Daley?' asked Strange, nodding his appreciation of the point.

Johnson grinned, but shook his head and continued.

The wife, Margaret Daley, felt a bit guilty about hanging on to the rucksack, and according to Daley persuaded him to drop it at Kidlington the next day, Wednesday – originally asserting that he'd found it that same morning. But he hadn't really got his story together, and it was soon pretty clear that the man wasn't a very good liar; and it wasn't long before he changed his story.

The rucksack itself? Apart from the pocket-buttons rusting a bit, it seemed reasonably new, containing, presumably, all the young woman's travelling possessions, including a passport which identified its owner as one Karin Eriksson, from an address in Uppsala Sweden. Nothing, it appeared, had been tampered with overmuch by the Daleys, but the contents had proved of only limited intersect the usual female toiletries, including toothpaste, Tampax, lipstic eye-shadow, blusher, comb, nail-file, tweezers, and white tissue an almost full packet of Marlboro cigarettes with a cheap 'throw-away' lighter; a letter, in Swedish, from a boyfriend, dated two months earlier, proclaiming (as was later translated) a love that was fully prepared to wait until eternity but which would also appreciate a further rendezvous a little earlier; a slim money wallet, containing no credit cards or travellers' cheques -just five ten-pound notes (newish but not consecutively numbered); a book of second-class English postage-stamps; a greyish plastic mac meticulously folded; a creased postcard depicting Velasquez's 'Rokeby Venus' on one side, and the address of the Welsh relative on the other; two clean (cleanish) pairs of pants; one faded-blue dress; three creased blouses, black, white, and darkish red…

'Get on with it,' mumbled Strange.

Well, Interpol were contacted, and of course the Swedish police A distraught mother, by phone from Uppsala, had told them that it was very unusual for Karin not to keep her family informed where she was and what she was up to – as she had done from London the previous week.

A poster ('Have you seen this young woman?') displaying blown-up copy of the passport photograph had been printed, and seen by some of the citizens of Oxford and its immediate environs in buses, youth clubs, information offices, employment agencises those sorts of places.

‘And that's when these people came forward, these witnesses?' interrupted Strange.

‘That's it, sir.'

‘And the fellow you took notice of was the one who thought he saw her in Sunderland Avenue.'

'He was a very good witness. Very good.'

'Mm! I don't know. A lovely leggy blonde – well-tanned, well-exposed, eh, Johnson? Standing there on the grass verge facing the traffic…Bit odd, isn't it? You'd've thought the fellow would've rembered her for certain – that's all I'm saying. Some of us still have the occasional erotic day-dream, y'know.'

‘That's what Morse said.'

‘Did he now!'

‘He said even if most of us were only going as far as Woodstock we'd have taken her on to Stratford, if that's what she wanted.'

'He'd have taken her to Aberdeen,' growled Strange.

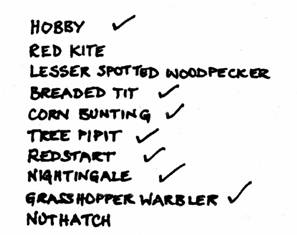

The next thing (Johnson continued his story) had been the discovery, in the long grass about twenty yards from where the rucksack had been found – probably fallen out of one of the pockets a slim little volume titled A Birdwatchers' Guide. Inside was a sheet of white paper, folded vertically and seemingly acting as a mark, on which the names of ten birds had been written in it capitals, with a pencilled tick against seven of them:

The lettering matched the style and slope of the few scraps of writing found in the other documents, and the easy conclusion was that Karin Eriksson had been a keen ornithologist, probably buying the book after arriving in London and trying to add to her list of sightings some of the rarer species which could be seen during English summers. The names of the birds were written English and there was only the one misspelling: the 'breaded tit? – an interesting variety of the 'bearded plaice' spotted fairly frequently in English restaurants. (It had been the pedantic Morse; who had made this latter point.)

Even more interesting, though, had been the second enclosure within the pages: a thin yellow leaflet, folded this time across middle, announcing a pop concert in the grounds of Blenheim Palace on Monday, 8 July – the day before the rucksack was found: 8 p.m.-11.3o p.m., admission (ticket only) £4.50.

That was it. Nothing else really. Statements taken – enquires made – searches organized in the grounds of Blenheim Palace but…

'How much did Morse come into all this?' asked a frowning Strange.

Johnson might have known he'd ask it, and he knew he might as well come clean.