Only he wasn’t. He was interested in Tesla.

Burke decided to take a break. Got to his feet and stretched. A girl with multiple piercings and blue streaks in her hair brought him a coffee that was strong and sweet. A pair of Israeli backpackers sat down at the terminal next to his.

Returning to his chair, he typed: “Tesla Symposium Belgrade 2005.” Twenty-three hits, most of them in a language he didn’t recognize. (Presumably Serbian.) But there were a couple in English.

The first was the home page for the Museum of Nikola Tesla, which contained a link to the symposium’s site. He wrote down the museum’s address, 51 Proleterskih brigada Street, then took the online tour, which guided him from room to room through the museum. Along with Tesla’s ashes, personal effects, and correspondence, there were many photographs, original patents, and models of his inventions. The museum also housed the Tesla archives, which included the documents his nephew had obtained from the U.S. government.

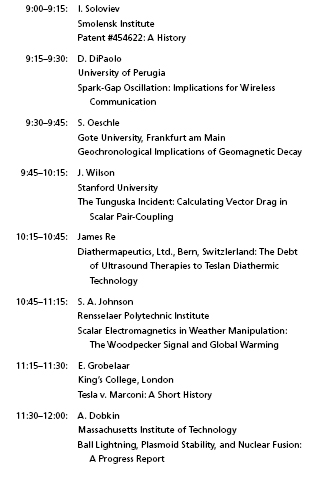

He returned to the Google list and clicked on the site “2006 Tesla Symposium, Belgrade,” which included details of the program. He scanned through, looking for d’Anconia’s name.

And so on. Looking through the list, the vocabulary alone drove home just how far out of his depth Burke was. Nucleons, flux intensity, Fourier frequencies, “magnetostatic scalar potential.”

And no “Francisco d’Anconia.”

He didn’t get it. He could hear the desk clerk’s voice, indignant that Burke had never heard of Tesla. But d’Anconia had. “Your friend – he gives speech! At the symphony.”

Then Burke had one of those realizations that begins with duhhh. He wasn’t looking for “d’Anconia.” He was looking for the man who had used that name as an alias, a joke, or an homage. If the guy he wanted to find had given a speech at the symposium, then he was one of the scientists listed in the program.

Burke sat back and sighed. Geomagnetic decay? Scalar weapons? This was not at all what he had in mind when he came to Belgrade, tracking “Francisco d’Anconia.”

He printed a copy of the symposium’s program, logged out, paid for the time he’d used, and began walking back to the Esplanade.

He was trying to get his head around it.

One point he had to give to Kovalenko: Some of Aherne’s clients were a little dodgy. He was pretty sure one guy was running an online poker game. That was illegal in the States but not in Europe. He suspected that another client was bootlegging Microsoft DVDs. And there were dozens of customers engaged in “creative” accounting where taxes were concerned.

D’Anconia didn’t fit in with that crowd. In fact, Kovalenko had all but called him a terrorist.

But if d’Anconia was one of the scientists on the list, well, it just didn’t make sense to Burke. In his view, terrorists don’t think about things like “vector drag,” and they don’t present papers at symposia.

They just don’t.

CHAPTER 24

It was dark and cold, and as Mike Burke walked back to the Esplanade, the snow was sifting down like flour out of the sky. The streetlights swarmed with snowflakes. Coming toward him, a woman in a long red coat walked with quick little steps, hunched against the cold.

The woman made him think of Kate and he found himself wishing that his wife was beside him. When the weather was like this, he’d put his arm around her, and pull her into the shelter of his shoulder. He could almost feel the warmth and weight of her. If she were here now, he would take her to one of the restaurants on the river, where they’d watch the light on the water, and drink red wine.

Snap out of it.

He turned the corner, and there was the Esplanade. He headed straight for the bar. Now that it was nighttime, half the little tables were occupied, with each one sporting a candle in a red glass. A brace of microphones on a tiny stage threatened live entertainment. He’d read in the guidebook that one of the musical specialties of Belgrade was a hybrid of techno and Serbian folk music called turbofolk.

The bar itself was more like a voodoo altar. A long blue mirror strung with Christmas lights looked down on dusty bottles of whiskey, gin, and vodka. Plastic cacti glowed green amid miniature Chinese lanterns, pink flamingos, paper angels, and bobbleheads of Marilyn, Jesus, and Elvis. A woman filled four mugs of beer, then turned to him with an inquiring look.

“I’m looking for Tooti,” Burke said, barely believing the words.

The woman behind the bar was forty, or maybe even fifty, with thinning hair and an unhealthy pallor. “You found her.”

“There was an American who stayed at the Esplanade in January. The desk clerk thought you might have seen him. About my age.”

She arched a plucked eyebrow.

“He wore a hat,” Burke added. “When I saw him, he was wearing a fedora, or whatever they’re called.”

She smiled. “He’s gay, this guy?”

Burke shook his head. “No. I mean, I don’t know.”

Her lips came together in a pout. “Then what do you care?”

He thought about lying, but the effort was almost too much. So what he said was: “It’s kind of complicated, but… my name’s Burke. I’ve come a really long way. Y’know?”

She looked at him for a moment, and then she nodded, as if deciding something. When she smiled, Burke realized that she must have been a very pretty girl. “His name was Frank.”

Burke lit up with surprise. “You remember him!”

“We don’t get so many Americans,” she explained. “Mostly, they go to the Intercon.”

“You want a drink?” Burke asked. He put a thousand-dinar note on the table. She poured herself a tumbler of Johnny Walker Black. Took a sip and frowned. “You’re not a cop?”

Burke shook his head.

“You don’t look like a cop.”

“What’s a cop look like?” he asked.

“Big muscles and little piggy eyes.” She leaned on the bar. “Last week, two guys come from the RDB. They ask about this ‘Frank’ guy.”

“RDB?”

She rolled her eyes. “State Security.”

“So what did they say?” Burke asked.

“Who cares? No one tells them anything.”

“Why not?”

“These same pricks are here two months ago. Arrest nice girls.” She paused. “Okay,” she admitted, “maybe they do prostitution. But no trouble, ever. Good tips, too.” She looked Burke in the eyes. “You tip?”

Burke nodded. “Oh, yeah. I’m always tipping.”

“Good! Because here, most people don’t tip. I blame communism.”

Burke nodded in sympathy. Tossed another thousand dinars on the bar.

“Anyway,” Tooti said, “nobody tells these cops nothing.”

“Y’know, your English is really good…”

“I’m in Chicago for twenty years. West side.”

“Really?! And then… what? You came back.”

“My mother was sick, so…” She threw back her scotch, as if it were a shot of tequila.

“She get better?” Burke asked. “I mean, is she all right?”

Tooti tilted her head and smiled, surprised that he’d asked. “Yeah,” she said. “She’s fine now. They cut it out.” She paused. “Look, I don’t mind telling you about this Frank of yours, but don’t get excited. I don’t know much.”

“You know his name. You call him Frank.”

She shook her head. “He called himself Frank. He’s coming in, has a couple of beers. He’s not so friendly.”

“So what did you talk about?” Burke asked.

“I said, ‘Hi. I’m Tooti.’ And he said, ‘Frank.’”

“That’s it?”

Tooti nodded. The dinars vanished.

Burke felt as if he’d been had. “He talk to anyone else?”

Tooti shook her head. “No. And it’s too bad. Good-looking boy like that. Some people flirt with him – girls, boys – he’s not so interested.” She thought for a moment. “Most of the time, he’s writing.”