Michelle de Kretser

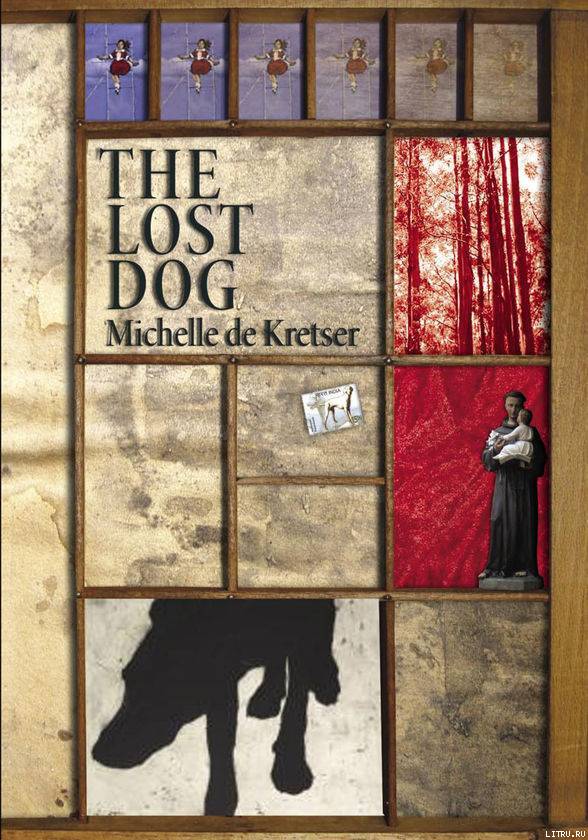

The Lost Dog

For Gus, of course

The whole of anything can never be told.

Henry James, Notebooks

Tuesday

Afterwards, he would remember paddocks stroked with light. He would remember the spotted trunks of gum trees; the dog arching past to sniff along the fence.

He cleaned his teeth at the tap on the water tank. The house in the bush had no running water, no electricity. It was only sporadically inhabited and had grown grimy with neglect. But Tom Loxley, spitting into the luxuriant weeds by the tap that November morning, thought, Light, air, space, silence. The Benedictine luxuries.

He placed his toothpaste and brush on a log at the foot of the steps; and later forgot where he had left them. Night would send him blundering about a room where torchlight swung across the wall, and what he could find and what he needed were not the same thing.

On the kitchen table, beside Tom’s laptop, was the printout of his book, Meddlesome Ghosts: Henry James and the Uncanny. He remembered the elation he had felt the previous evening, drafting the final paragraph; the impression that he had nailed it all down at last. It was to this end that he had rented Nelly Zhang’s house for four days, days in which he had written fluently and with conviction; to his surprise, because he was in the habit of proceeding hesitantly, and the book had been years in the making.

He owed this small triumph to Nelly, who had said, ‘It’s what you need. No distractions, and you won’t have to worry about kennels.’

This evidence of her concern had moved Tom. At the same time, he thought, She wants the money. The web of their relations was shot through with these ambivalences, shade and bright twined with such cunning that their pattern never settled.

His jacket hung on the back of a chair. He put it on, then paused: shuffled pages, squared off the stack of paper, touched what he had accomplished. James’s dictum caught his eye: Experience is never limited, and it is never complete.

When Tom called, raising his voice, the dog went on nosing through leaves and damp grass. It was their last morning there; the territory was no longer new. Yet whenever the dog was allowed outside, he would race to the far end of the yard and start working his way along the fence. Instinct, deepened over centuries, compelled him to check boundaries; drew him to the edges of knowledge.

Afterwards, Tom would remember the dog ignoring him, and the spurt of impatience he had felt. The dog had to be walked and the house packed up before the long drive back to the city. He was keen to get moving while the weather held. So he didn’t pat the dog’s soft head when he strode to the fence and reached for him.

The dog was standing still, one forepaw raised; listening.

Tea-coloured puddles sprawled on the track. A cockatoo fl ying up from a sapling dislodged a rhinestone spray. It was a wet spring even in the city, and in these green hills, it rained and rained.

The dog’s paw-pads were shining jet. He sniffed, and sneezed, and plunged into dithering grass. A twenty-foot rope kept him from farmland and forest while affording him greater freedom than his lead.

The man picking his way through rutted mud at the other end of the rope disliked the cold. Tom Loxley had spent two-thirds of his life in a cool southern city. But his childhood had been measured in monsoons, and the first windows he knew had contained the Arabian Sea. Free hand shoved deep in his pocket, he held himself tight against the morning.

Light rubbed itself over the paddocks. It struck silver from the cockatoo and splintered the windscreen of a toy truck threading up the mountain where trees went down to steel. But what Tom took from the scene was the thrust and weight of leaves, the season’s green upswinging. Over time, his eye had grown accustomed to the bleached pigments of the continent where he had made his life. But love takes shape before we know it. On a damp, plumed coast in India, Tom’s fi rst encounter with landscape had been dense with leaves. A faultless place for him would always be a green one.

He glanced back at Nelly’s house. Afterwards, he would remember his sense that everything-the pepper tree by the gate, the sloping driveway, the broad blue sky itself-was holding its breath, gathered to the moment. The impression was forceful, but Tom’s thoughts were busy with Nelly as he had once seen her: astride a sunny wall in the suburb where they both lived, a striped cat pouring himself through her arms.

In the corner of his eye, something blurred. At the same time, the rope skidded through his fi ngers. His head snapped around to see grey fur moving fast, and the dog in pursuit, the end to which sinew and nerve and tissue had always been building.

Tom swooped for the rope, and clawed at air. On the hillside above the track, the dog was swallowed by leaves.

Birdsong, and eucalyptus-scented air.

A lean white dog, rust-splotched, springing up a bank.

Things Tom Loxley would remember.

It had begun, seven months earlier, with a painting.

April becalmed in hazy, slanted light. Tom clipped on the dog’s lead and they left his flat to walk in streets where houses were packed like wheat. Windows were turning yellow. Dahlias showed off like sunsets. On an autumn evening in the city, Tom looked sideways at other people’s lives.

At a gallery he hadn’t entered in the four years since his wife left, long sash windows had been pushed up; there were smokers on the terraces with glasses in their hands. Tom tied the dog to the garden side of the ornate iron railings and went up the steps.

A group show: four young artists. Their friends and relatives were congratulatory and numerous in the two rooms on the ground floor. Tom drank cold wine and looked at paintings. They seemed unremarkable but he knew enough to know he couldn’t tell.

From the street it had seemed there were fewer people upstairs. He had his glass refilled by a pierced girl with ruffl es of hair parted low on the side, and started up the stairs. But something made him glance back. She was looking up at him, her face gleaming and amused; and he realised, with a little lurch of perception, that she was a boy.

The fi rst-floor room that ran the width of the building contained work unrelated to the exhibition below. A well-fleshed man stood in front of a painting, blocking it from view.

‘Eddie’s still channelling Peter, it seems.’ He had a thin, carrying voice. A dark boy standing beside him snickered.

On the short wall opposite the door was an almost-abstract landscape at which Tom looked for four or five minutes; a long time. Then he went out onto the balcony and saw a couple leaving the gallery stop to fondle the dog’s floppy ears. The word Beefmaster passed on the side of a van.

When Tom stepped back through the fl oor-length window, the large man was in the centre of the room. More people had attached themselves to his group. He gazed out over their heads; his face was round and turnip-white. The pallor made his eyes, which were very dark, appear hollow. He murmured as Tom passed. There was a small explosion of laughter.

Tom gulped wine in front of the picture opposite the door. His scalp hummed. He thought, I am the wrong kind of thing. He thought, I don’t belong here. The adverb having a wide application.

By an act of will, he directed his attention to the landscape in front of him. His formal training in art history was limited to two undergraduate years. They had left him a vocabulary, formal strategies for thinking about images. He believed himself to possess a set of basic analytical tools for operating upon a work of art.