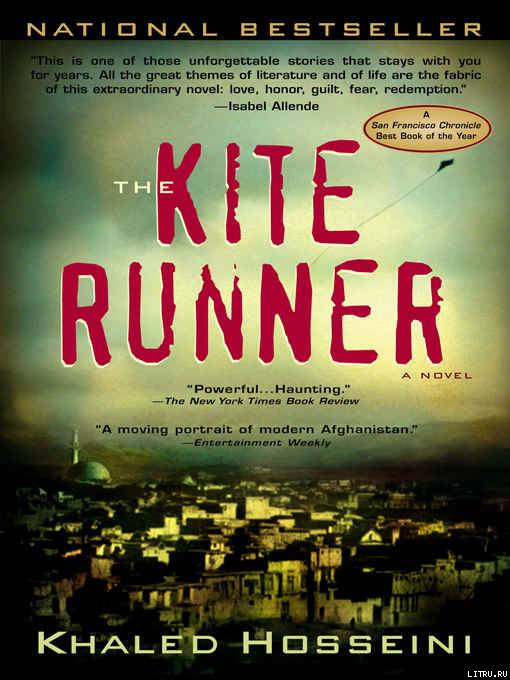

Khaled Hosseini

The Kite Runner

This book is dedicated to Haris and Farah, both the noor of my eyes, and to the children of Afghanistan.

ONE

December 2001

I became what I am today at the age of twelve, on a frigid overcast day in the winter of 1975. I remember the precise moment, crouching behind a crumbling mud wall, peeking into the alley near the frozen creek. That was a long time ago, but it’s wrong what they say about the past, I’ve learned, about how you can bury it. Because the past claws its way out. Looking back now, I realize I have been peeking into that deserted alley for the last twenty-six years.

One day last summer, my friend Rahim Khan called from Pakistan. He asked me to come see him. Standing in the kitchen with the receiver to my ear, I knew it wasn’t just Rahim Khan on the line. It was my past of unatoned sins. After I hung up, I went for a walk along Spreckels Lake on the northern edge of Golden Gate Park. The early-afternoon sun sparkled on the water where dozens of miniature boats sailed, propelled by a crisp breeze. Then I glanced up and saw a pair of kites, red with long blue tails, soaring in the sky. They danced high above the trees on the west end of the park, over the windmills, floating side by side like a pair of eyes looking down on San Francisco, the city I now call home. And suddenly Hassan’s voice whispered in my head: For you, a thousand times over. Hassan the harelipped kite runner.

I sat on a park bench near a willow tree. I thought about something Rahim Khan said just before he hung up, almost as an afterthought. There is a way to be good again. I looked up at those twin kites. I thought about Hassan. Thought about Baba. Ali. Kabul. I thought of the life I had lived until the winter of 1975 came along and changed everything. And made me what I am today.

TWO

When we were children, Hassan and I used to climb the poplar trees in the driveway of my father’s house and annoy our neighbors by reflecting sunlight into their homes with a shard of mirror. We would sit across from each other on a pair of high branches, our naked feet dangling, our trouser pockets filled with dried mulberries and walnuts. We took turns with the mirror as we ate mulberries, pelted each other with them, giggling, laughing. I can still see Hassan up on that tree, sunlight flickering through the leaves on his almost perfectly round face, a face like a Chinese doll chiseled from hardwood: his flat, broad nose and slanting, narrow eyes like bamboo leaves, eyes that looked, depending on the light, gold, green, even sapphire. I can still see his tiny low-set ears and that pointed stub of a chin, a meaty appendage that looked like it was added as a mere afterthought. And the cleft lip, just left of midline, where the Chinese doll maker’s instrument may have slipped, or perhaps he had simply grown tired and careless.

Sometimes, up in those trees, I talked Hassan into firing walnuts with his slingshot at the neighbor’s one-eyed German shepherd. Hassan never wanted to, but if I asked, really asked, he wouldn’t deny me. Hassan never denied me anything. And he was deadly with his slingshot. Hassan’s father, Ali, used to catch us and get mad, or as mad as someone as gentle as Ali could ever get. He would wag his finger and wave us down from the tree. He would take the mirror and tell us what his mother had told him, that the devil shone mirrors too, shone them to distract Muslims during prayer. “And he laughs while he does it,” he always added, scowling at his son.

“Yes, Father,” Hassan would mumble, looking down at his feet. But he never told on me. Never told that the mirror, like shooting walnuts at the neighbor’s dog, was always my idea.

The poplar trees lined the redbrick driveway, which led to a pair of wrought-iron gates. They in turn opened into an extension of the driveway into my father’s estate. The house sat on the left side of the brick path, the backyard at the end of it.

Everyone agreed that my father, my Baba, had built the most beautiful house in the Wazir Akbar Khan district, a new and affluent neighborhood in the northern part of Kabul. Some thought it was the prettiest house in all of Kabul. A broad entryway flanked by rosebushes led to the sprawling house of marble floors and wide windows. Intricate mosaic tiles, handpicked by Baba in Isfahan, covered the floors of the four bathrooms. Gold-stitched tapestries, which Baba had bought in Calcutta, lined the walls; a crystal chandelier hung from the vaulted ceiling.

Upstairs was my bedroom, Baba’s room, and his study, also known as “the smoking room,” which perpetually smelled of tobacco and cinnamon. Baba and his friends reclined on black leather chairs there after Ali had served dinner. They stuffed their pipes – except Baba always called it “fattening the pipe” – and discussed their favorite three topics: politics, business, soccer. Sometimes I asked Baba if I could sit with them, but Baba would stand in the doorway. “Go on, now,” he’d say. “This is grown-ups’ time. Why don’t you go read one of those books of yours?” He’d close the door, leave me to wonder why it was always grown-ups’ time with him. I’d sit by the door, knees drawn to my chest. Sometimes I sat there for an hour, sometimes two, listening to their laughter, their chatter.

The living room downstairs had a curved wall with custom-built cabinets. Inside sat framed family pictures: an old, grainy photo of my grandfather and King Nadir Shah taken in 1931, two years before the king’s assassination; they are standing over a dead deer, dressed in knee-high boots, rifles slung over their shoulders. There was a picture of my parents’ wedding night, Baba dashing in his black suit and my mother a smiling young princess in white. Here was Baba and his best friend and business partner, Rahim Khan, standing outside our house, neither one smiling – I am a baby in that photograph and Baba is holding me, looking tired and grim. I’m in his arms, but it’s Rahim Khan’s pinky my fingers are curled around.

The curved wall led into the dining room, at the center of which was a mahogany table that could easily sit thirty guests – and, given my father’s taste for extravagant parties, it did just that almost every week. On the other end of the dining room was a tall marble fireplace, always lit by the orange glow of a fire in the wintertime.

A large sliding glass door opened into a semicircular terrace that overlooked two acres of backyard and rows of cherry trees. Baba and Ali had planted a small vegetable garden along the eastern wall: tomatoes, mint, peppers, and a row of corn that never really took. Hassan and I used to call it “the Wall of Ailing Corn.”

On the south end of the garden, in the shadows of a loquat tree, was the servants’ home, a modest little mud hut where Hassan lived with his father.

It was there, in that little shack, that Hassan was born in the winter of 1964, just one year after my mother died giving birth to me.

In the eighteen years that I lived in that house, I stepped into Hassan and Ali’s quarters only a handful of times. When the sun dropped low behind the hills and we were done playing for the day, Hassan and I parted ways. I went past the rosebushes to Baba’s mansion, Hassan to the mud shack where he had been born, where he’d lived his entire life. I remember it was spare, clean, dimly lit by a pair of kerosene lamps. There were two mattresses on opposite sides of the room, a worn Herati rug with frayed edges in between, a three-legged stool, and a wooden table in the corner where Hassan did his drawings. The walls stood bare, save for a single tapestry with sewn-in beads forming the words Allah-u-akbar. Baba had bought it for Ali on one of his trips to Mashad.