chimp

woman

orangutan

gorilla

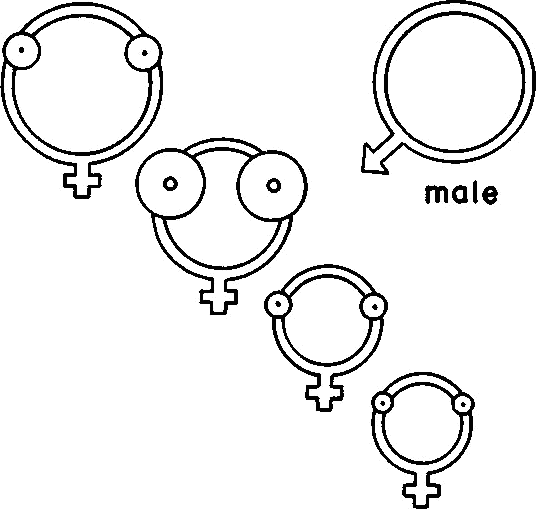

Human females are unique in their breasts, which are considerably larger than those of apes even before the first pregnancy. The main circles represent female body size relative to male body size of the same species.

It turns out that, among polygynous mammals, average harem size increases with the ratio of the male's body size to the female's body size. That is, the biggest harems are typical of species in which males are much larger than females. For example, males and females are the same size in gibbons, which are monogamous; male gorillas, with a typical harem of three to six females, weigh nearly double the weight of each female; but the average harem is forty-eight wives for the southern elephant seal, whose 3-ton male dwarfs his 700-pound wives. The explanation is that, in a monogamous species, every male can win a female, but in a very polygynous species most males languish without any mate, because a few dominant males have succeeded in rounding up all the females into their harems. Hence, the bigger the harem, the fiercer is the competition among males and the more important it is for a male to be big, since the bigger male usually wins the fights. We humans, with our slightly bigger males and slight polygyny, fit this pattern. (However, at some point in human evolution, male intelligence and personality came to count for Wore than size: male basketball players and sumo wrestlers don't tend to have more wives than male jockeys or coxswains.) Because competition for mates is fiercer in polygynous than in monogamous species, the polygynous species also tend to have more marked differences between males and females in other respects besides body size. These differences are the secondary sexual characteristics that play a role in attracting mates. For instance, males and females of the monogamous gibbons look identical at a distance, while male gorillas (befitting their polygyny) are easily recognized by their crested heads and silver-haired backs. Here too, our anatomy reflects our mild polygyny. The external differences between men and women are not nearly as marked as sex-related differences in gorillas or orangutans, but the zoologist from outer space could probably still distinguish men and women by the body and facial hair of men, men's unusually large penis, and the large breasts of women even before first pregnancy (in this we are unique among primates).

Proceeding now to the genitalia themselves, the combined weight of the testes in the average man is about \Vi ounces. This may boost the macho man's ego when he reflects on the slightly lower testis weight in a 450-pound male gorilla. But wait—our testes are dwarfed by the 4-ounce testes of a 100-pound male chimpanzee. Why is the gorilla so economical, and the chimp so well-endowed, compared to us?

The Theory of Testis Size is one of the triumphs of modern physical anthropology. By weighing the testes of thirty-three primate species, British scientists identified two trends: species that copulate more often need bigger testes; and promiscuous species in which several males routinely copulate in quick sequence with one female need especially big testes (because the male that injects the most semen has the best chance of being the one to fertilize the egg). When fertilization is a competitive lottery, large testes enable a male to enter more sperm-tickets in the lottery.

Here is how these considerations account for the differences in testis size among the great apes and humans. A female gorilla does not resume sexual activity until three or four years after giving birth, and she is receptive for only a couple of days a month until she becomes pregnant again. So even the successful male gorilla with a harem of several females experiences sex as a rare treat—if he is lucky, a few times a year. His relatively tiny testes are quite adequate for those modest demands. The sex life of a male orangutan may be somewhat more demanding, but not much. However, each male chimp in a promiscuous troop of many females lives in sexual nirvana, with nearly daily opportunities to copulate for a common chimp and several daily copulations for the average pygmy chimp. That, plus his need to outdo other male chimps in semen output if he is to fertilize the promiscuous female, explains his need for gigantic testes. We humans make do with medium-sized testes because the average man copulates more often than gorillas or orangutans but less often than chimps. In addition, the typical woman in a typical menstrual cycle does not force several men into sperm competition to fertilize her.

Thus, primate testis design well illustrates the principles of trade-offs and evolutionary cost/benefit analyses explained on page 52. Each species has testes big enough to do their job, but not unnecessarily larger ones. Bigger testes would just entail more costs without proportional benefits, by diverting space and energy from other tissues and increasing the risk of testicular cancer.

From this triumph of scientific explanation we descend to a glaring failure: the inability of twentieth-century science to formulate an adequate Theory of Penis Length. The length of the erect penis averages 1 Vi inches in a gorilla, 1 Vz inches in an orangutan, 3 inches in a chimp, and 5 inches in a man. Visual conspicuousness varies in the same sequence: a gorilla's penis is inconspicuous even when erect because of its black colour, while the chimp's pink erect penis stands out against the bare white skin behind it. The flaccid penis is not even visible in apes. Why does the human male need his relatively enormous, attention-getting penis, which is larger than that of any other primate? Since the male ape successfully propagates his kind with much less, does not the human penis represent largely wasted protoplasm that would be more valuable if devoted, say, to cerebral cortex or improved fingers?

Biologist friends to whom I pose this conundrum usually think of distinctive features of human coitus where they suppose a long penis might somehow be useful: our frequent use of the face-to-face position, our acrobatic variety of coital positions, and the supposedly long duration of our coital bouts. None of these explanations survives close scrutiny. The face-to-face position is also a preferred one for orangutans and pygmy chimps, and is used occasionally by gorillas. Orangutans vary face-to-face copulation with dorso-ventral and sideways positions, and do it while hanging from branches of trees—surely that demands more penile acrobatics than our comfortable boudoir exercises. Our mean duration of coitus (about four minutes for Americans) is much longer than for gorillas (one minute), pygmy chimps (fifteen seconds), or common chimps (seven seconds), but shorter than for orangutans (fifteen minutes) and lightning-fast compared to the twelve-hour-long copulations of marsupial mice. (Are you listening, ghosts of Errol Flynn and Don Juan?)

Since it thus seems unlikely that special features of human coitus demand a large penis, a popular alternative theory is that the human penis has also become an organ of display, like a peacock's tail or a lion's mane. This theory is reasonable but begs the question, what type of display, and to whom?

Proud male anthropologists unhesitatingly answer, an attractive display, to women, but this represents mere wishful thinking. Many women say that they are turned on by a man's voice, legs, and shoulders more than by the sight of his penis. A telling point is that the women's magazine Viva initially published photos of nude men but dropped them after surveys showed lack of female interest. When Vivas nude men disappeared, the number of female readers increased, and the number of male readers decreased. Evidently, the male readers were the ones buying Viva for its nude photos. While we can agree that the human penis is an organ of display, the display is intended not for women but for fellow men. icn.