• Target - There is generally a target set for each rule in a ruleset. If the rule has matched fully, the target specification tells us what to do with the packet. For example, if we should drop or accept it, or NAT it, etc. There is also something called a jump specification, for more information see the jump description in this list. As a last note, there might not be a target or jump for each rule, but there may be.

• Rule - A rule is a set of a match or several matches together with a single target in most implementations of IP filters, including the iptables implementation. There are some implementations which let you use several targets/actions per rule.

• Ruleset - A ruleset is the complete set of rules that are put into a whole IP filter implementation. In the case of iptables, this includes all of the rules set in the filter, nat, raw and mangle tables, and in all of the subsequent chains. Most of the time, they are written down in a configuration file of some sort.

• Jump - The jump instruction is closely related to a target. A jump instruction is written exactly the same as a target in iptables, with the exception that instead of writing a target name, you write the name of another chain. If the rule matches, the packet will hence be sent to this second chain and be processed as usual in that chain.

• Connection tracking - A firewall which implements connection tracking is able to track connections/streams simply put. The ability to do so is often done at the impact of lots of processor and memory usage. This is unfortunately true in iptables as well, but much work has been done to work on this. However, the good side is that the firewall will be much more secure with connection tracking properly used by the implementer of the firewall policies.

• Accept - To accept a packet and to let it through the firewall rules. This is the opposite of the drop or deny targets, as well as the reject target.

• Policy - There are two kinds of policies that we speak about most of the time when implementing a firewall. First we have the chain policies, which tells the firewall implementation the default behaviour to take on a packet if there was no rule that matched it. This is the main usage of the word that we will use in this book. The second type of policy is the security policy that we may have written documentation on, for example for the whole company or for this specific network segment. Security policies are very good documents to have thought through properly and to study properly before starting to actually implement the firewall.

How to plan an IP filter

One of the first steps to think about when planning the firewall is their placement. This should be a fairly simple step since mostly your networks should be fairly well segmented anyway. One of the first places that comes to mind is the gateway between your local network(s) and the Internet. This is a place where there should be fairly tight security. Also, in larger networks it may be a good idea to separate different divisions from each other via firewalls. For example, why should the development team have access to the human resources network, or why not protect the economic department from other networks? Simply put, you don't want an angry employee with the pink slip tampering with the salary databases.

Simply put, the above means that you should plan your networks as well as possible, and plan them to be segregated. Especially if the network is medium- to big-sized (100 workstations or more, based on different aspects of the network). In between these smaller networks, try to put firewalls that will only allow the kind of traffic that you would like.

It may also be a good idea to create a De-Militarized Zone (DMZ) in your network in case you have servers that are reached from the Internet. A DMZ is a small physical network with servers, which is closed down to the extreme. This lessens the risk of anyone actually getting in to the machines in the DMZ, and it lessens the risk of anyone actually getting in and downloading any trojans etc. from the outside. The reason that they are called de-militarized zones is that they must be reachable from both the inside and the outside, and hence they are a kind of grey zone (DMZ simply put).

There are a couple of ways to set up the policies and default behaviours in a firewall, and this section will discuss the actual theory that you should think about before actually starting to implement your firewall, and helping you to think through your decisions to the fullest extent.

Before we start, you should understand that most firewalls have default behaviours. For example, if no rule in a specific chain matches, it can be either dropped or accepted per default. Unfortunately, there is only one policy per chain, but this is often easy to get around if we want to have different policies per network interface etc.

There are two basic policies that we normally use. Either we drop everything except that which we specify, or we accept everything except that which we specifically drop. Most of the time, we are mostly interested in the drop policy, and then accepting everything that we want to allow specifically. This means that the firewall is more secure per default, but it may also mean that you will have much more work in front of you to simply get the firewall to operate properly.

Your first decision to make is to simply figure out which type of firewall you should use. How big are the security concerns? What kind of applications must be able to get through the firewall? Certain applications are horrible to firewalls for the simple reason that they negotiate ports to use for data streams inside a control session. This makes it extremely hard for the firewall to know which ports to open up. The most common applications works with iptables, but the more rare ones do not work to this day, unfortunately

Note There are also some applications that work partially, such as ICQ. Normal ICQ usage works perfectly, but not the chat or file sending functions, since they require specific code to handle the protocol. Since the ICQ protocols are not standardized (they are proprietary and may be changed at any time) most IP filters have chosen to either keep the ICQ protocol handlers out, or as patches that can be applied to the firewalls. Iptables have chosen to keep them as separate patches.

It may also be a good idea to apply layered security measures, which we have actually already discussed partially so far. What we mean with this, is that you should use as many security measures as possible at the same time, and don't rely on any one single security concept. Having this as a basic concept for your security will increase security tenfold at least. For an example, let's look at this.

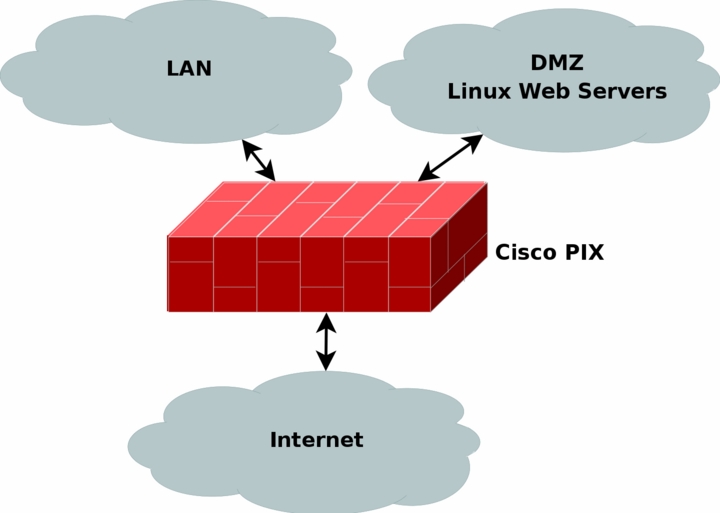

As you can see, in this example I have in this example chosen to place a Cisco PIX firewall at the perimeter of all three network connections. It may NAT the internal LAN, as well as the DMZ if necessary. It may also block all outgoing traffic except http return traffic as well as ftp and ssh traffic. It can allow incoming http traffic from both the LAN and the Internet, and ftp and ssh traffic from the LAN. On top of this, we note that each webserver is based on Linux, and can hence throw iptables and netfilter on each of the machines as well and add the same basic policies on these. This way, if someone manages to break the Cisco PIX, we can still rely on the netfilter firewalls locally on each machine, and vice versa. This allows for so called layered security.

On top of this, we may add Snort on each of the machines. Snort is an excellent open source network intrusion detection system (NIDS) which looks for signatures in the packets that it sees, and if it sees a signature of some kind of attack or breakin it can either e-mail the administrator and notify him about it, or even make active responses to the attack such as blocking the IP from which the attack originated. It should be noted that active responses should not be used lightly since snort has a bad behaviour of reporting lots of false positives (e.g., reporting an attack which is not really an attack).