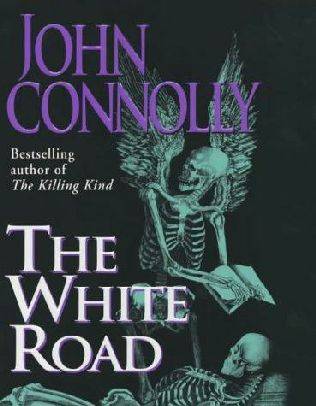

John Connolly

The White Road

The fourth book in the Charlie Parker series

To Darley Anderson

I

Who is the third who walks always beside you? When I count, there are only you and I together But when I look ahead up the white road There is always another one walking beside you Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded I do not know whether a man or a woman -But who is that on the other side of you?

– T. S. ELIOT, THE WASTE LAND

Prologue

They are coming in their trucks and their cars, plumes of blue smoke following them through the clear night air like stains upon the soul. They are coming with their wives and their children, with their lovers and their sweethearts, talking of crops and animals and journeys they will make; of church bells and Sunday schools; of wedding dresses and the names of children yet unborn; of who said this and who said that, things small and great, the lifeblood of a thousand small towns no different from their own.

They are coming with food and drink, and the smell of fried chicken and fresh-baked pies makes their mouths water. They are coming with dirt beneath their nails and beer on their breath. They are coming in pressed shirts and patterned dresses, hair combed and hair wild. They are coming with joy in their hearts and vengeance on their minds and excitement curling like a snake in the hollow of their bellies.

They are coming to see the burning man.

The two men stopped at Cebert Yaken’s gas station, “The Friendliest Little Gas Station in the South,” close by the banks of the Ogeechee River on the road to Caina. Cebert had painted the sign himself in 1968 in bright yellows and reds, and every year since then he had climbed onto the flat roof on the first day of April to freshen the colors, so that the sun would never take its toll upon the sign and cause the welcome to fade. Each day, the sign cast its shadow on the clean lot, on the flowers in their boxes, on the shining gas pumps, and on the buckets filled with water so that drivers could wipe the remains of bugs from their windshields. Beyond lay untilled fields, and in the early September heat the shimmer rising from the road made the sassafras dance in the still air. The butterflies mixed with the falling leaves, sleepy oranges and checkered whites and eastern tailed-blues bouncing upward in the wake of passing vehicles like the sails of brightly colored ships tossing on a wild sea.

From his stool by the window, Cebert would look out on the arriving cars, checking for out-of-state tags so that he could prepare a good old Southern welcome, maybe sell some coffee and doughnuts or shift some of the tourist maps, the yellowing of their covers in the sunlight signaling the approaching end of their usefulness.

Cebert dressed the part: he wore blue overalls with his name sewn on the left breast, and a Co-Op Beef Feeds cap set way back on his head like an afterthought. His hair was white and he had a long mustache that curled exotically over his upper lip, the two ends almost meeting on his chin. Behind his back folks said that it made Cebert look like a bird had just flown up his nose, but they didn’t mean nothing by it. Cebert’s family had lived in these parts for generations and Cebert was one of their own. He advertised bake sales and picnics in the windows of his gas station and donated to every good cause that came his way. If dressing and acting like Grandpa Walton helped him sell a little more gas and a couple of extra candy bars, then good luck to Cebert.

Above the wooden counter, behind which Cebert sat day in, day out, seven days each week, sharing the duties with his wife and his boy, was a bulletin board headed: “Look Who Dropped By!” Pinned to it were hundreds of business cards. There were more cards on the walls and the window frames, and on the door that led into Cebert’s little back office. Thousands of Abe B. Normals or Bob R. Averages, passing through Georgia on their way to sell more photocopy ink or hair-care products, had handed old Cebert their cards so that they could leave a reminder of their visit to the Friendliest Little Gas Station in the South. Cebert never took them down, so that card had piled upon card in a process of accretion, layering like rock. True, some had fallen over the years, or slipped behind the coolers, but for the most part if the Abe B.’s or Bob R.’s passed through again, with a little Abe or Bob in tow, there was a pretty good chance that they would find their cards buried beneath a hundred others, relics of the lives that they had once enjoyed and of the men that they had once been.

But the two men who paid for a full tank and put water in the steaming engine of their piece-of-shit Taurus just before five that afternoon weren’t the kind who left their business cards. Cebert saw that straight off, felt it as something gave in his belly when they glanced at him. They carried themselves in a way that suggested barely suppressed menace and a potential for lethality that was as definite as a cocked gun or an unsheathed blade. Cebert barely nodded at them when they entered and he sure as hell didn’t ask them for a card. These men didn’t want to be remembered, and if, like Cebert, you were smart, then you’d pretty much do your best to forget them as soon as they’d paid for their gas (in cash, of course) and the last dust from their car had settled back on the ground.

Because if at some later date you did decide to remember them, maybe when the cops came asking and flashing descriptions, then, well, they might hear about it and decide to remember you too. And the next time someone dropped by to see old Cebert they’d be carrying flowers and old Cebert wouldn’t get to shoot the breeze or sell them a fading tourist map because old Cebert would be dead and long past worrying about yellowing stock and peeling paint.

So Cebert took their money and watched as the shorter one, the little white guy who had topped up the water when they pulled into the gas station, flicked through the cheap CDs and the small stock of paperbacks that Cebert kept on a rack by the door. The other man, the tall black one with the black shirt and the designer jeans, was looking casually at the corners of the ceiling and the shelves behind the counter loaded high with cigarettes. When he was satisfied that there was no camera, he removed his wallet and, using leather-gloved fingers, counted out two tens to pay for the gas and two sodas, then waited quietly while Cebert made change. Their car was the only one at the pumps. It had New York plates and both the plates and the car were kind of dirty, so Cebert couldn’t see much except for the make and the color and Miss Liberty peering through the murk.

“You need a map?” asked Cebert, hopefully. “Tourist guide, maybe?”

“No, thank you,” said the black man.

Cebert fumbled in the register. For some reason, his hands had started to shake. Nervous, he found himself making just the kind of inane conversation that he had vowed to avoid. He seemed to be standing outside himself, watching while an old fool with a drooping mustache talked himself into an early grave.

“You staying around here?”

“No.”

“Guess we won’t be seeing you again, then.”

“Maybe you won’t.”

There was a tone in the man’s voice that made Cebert look up from the register. Cebert’s palms were sweating. He flicked a quarter up with his index finger and felt it slide around in a loop in the hollow of his right hand before rattling back into the register drawer. The black man was still standing relaxed on the other side of the counter but there was a tightness around Cebert’s throat that he could not explain. It was as if the visitor were two people, one in black jeans and a black shirt with a soft Southern twang to his voice, and the other an unseen presence that had found its way behind the counter and was now slowly constricting Cebert’s airways.