I had fallen prostrate on the ground with the violence of the earthquake, but though I was sore afraid I could not take my eyes from the scene. The devouring mist was spreading even toward the shore, and through it I could see gouts of red and purple fire, shooting into the air like unto heaven, then falling back into the sea with a thousand tongues of flame. And through it all the great Eye descended, surrounded by flames so white and bright they pierced all, even the great mist. It seemed to me it dropped with a great deliberation. And when it did hit the surface of the sea, the firmament was riven by a shudder of such force and magnitude that it far surpassed any power of description. And these roars and quakes did continue for nigh unto an hour, shaking the earth with such violence I was certain the fabric of the land would tear itself apart. Only with the long passing of time did the groaning slowly pass away and the mists begin to clear.

O strange and terrible! It seemed the devil had falsely deceived the people of Staafhörn, luring them to a most lamentable end under angelic guise. Because when at last the mists did clear, the sea had turned a deep red and was covered as far as the eye could see with dead fish and other denizens of the deep-but of the fishing boats, or my fellow villagers, there was not the slightest sign. Yet in my lamentation and grief I was also sore perplexed, for would not Lucifer have stayed to gloat over his victory? But of the great Eye of white fire there was no sign. It was as if the awful fate of those in the three dozen boats was but a matter of indifference to the foul fiend.

For many days thereafter I wandered Denmark, telling my story to all that would listen and heed my warning. But forthwith, I was branded a heretic and quit the kingdom in fear of my life. I stop here at Grimwold Castle only briefly, for succor and sustenance; where I go from here I know not, but go I must.

Jón Albarn

Committed to paper by Martin of Brescia, who hereby gives solemn oath that this account has been faithfully recorded. Candlemas, anno Domini 1398.

When Crane at last put the pages aside, lay back, and turned off the light, the great weariness he felt had not abated. And yet he lay in bed, awake, his head filled with a single image: a vast eye, unblinking and wreathed in a pure white flame.

25

The door to John Marris's lab was open, but Asher knocked anyway.

"Come in," the cryptologist said.

Marris had the neatest lab in the Facility. Not a speck of dust was visible. Other than a half dozen manuals stacked carefully in one corner, his desk was empty except for keyboard and flat-screen terminal. There were no photographs, posters, or personal mementos of any kind. But, Asher reflected, that was typical of Marris: shy, withdrawn, almost secretive about his personal life and opinions alike. Wholly devoted to his work. Perfect qualities for a cryptologist.

What a shame, then, that his current project-such a short and apparently simple code-was proving so elusive.

Asher closed the door behind him, sat down in the sole visitor's chair. "I got your message," he said. "Any luck on the brute-force attacks?"

Marris shook his head.

"The random-byte filters?"

"Nothing intelligible."

"I see." Asher slumped in the chair. When he'd gotten the e-mail from Marris asking him to stop by at his earliest convenience, he'd felt a surge of hope that the man had deciphered the code. Coming from the phlegmatic Marris, "earliest convenience" was practically a shouted plea for immediate consultation. "What is it, then?"

Marris glanced at him, then looked away again. "I was wondering if, perhaps, we were approaching this decryption from the wrong angle."

Asher frowned. "Explain."

"Very well. Last night I was reading a book on the life of Alan Turing."

This was no surprise to Asher. A consummate academic, Marris was working toward a second doctorate, this time in the history of computing-and Alan Turing was a seminal figure in early computer theory. "Go on."

"Well…do you know what a Turing machine is?"

"You'd better refresh my memory."

"In the 1930s, Alan Turing posited a theoretical computer known as a Turing machine. It was composed of a 'tape,' a paper ribbon of arbitrarily extendable length. This tape was covered with symbols from some finite alphabet. A 'head' would run over the tape, reading the symbols and interpreting them, based on a lookup table. The state of the head would change, depending on the symbols it read. The tape itself could store either data or 'transitions,' by which he meant small programs. In today's computers, the tape would be the memory and the head the microprocessor. Turing declared this theoretical computer could solve any calculation."

"Go on," Asher said.

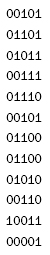

"I started thinking about this code we're trying to decrypt." And Marris waved his hand at the computer screen, where the signal emitted by the sentinel's pulses of light sat, almost taunting in its brevity and opacity:

"I wondered: what if this was a Turing tape?" Marris continued. "What would these zeros and ones do if we ran them through a Turing machine?"

Slowly, Asher sat forward. "You're suggesting those eighty bits…are a computer program?"

"I know it sounds crazy, sir-"

No crazier than the very fact of our being down here, Asher thought. "Please continue."

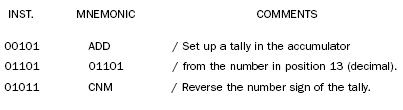

"Very well. First, I had to break the string of zeros and ones down into individual commands. I made the assumption that the initial values, five zeros and five ones, were placeholders to signify the length of each instruction-each digital 'word' thus being five bits in length. That left me with fourteen five-bit instructions." Marris tapped a key, and the long string of numbers vanished, to be replaced by a series of ordered rows:

Asher stared at the screen. "Awfully short for a computer program."

"Yes. Clearly, it would have to be a very simple computer program. And in machine language-the most basic, and universal, of digital languages."

Asher nodded. "And then?"

"When I got to my office this morning, I wrote a short routine that would compare these values against a master list of standard machine-language instructions. The routine assigned all possible instructions to the values, one after another, and then checked to see if any workable computer program emerged."

"What makes you think these-whoever is sending us the message uses the same kind of machine language instructions that we do?"

"At a binary level, sir, there are certain irreducible digital instructions that would be common to any conceivable computing device: increment, decrement, jump, skip if zero, Boolean logic. So I let the routine run and went on with my other work."

Asher nodded.

"About twenty minutes ago, the routine completed its run."

"Did those fourteen lines of binary translate to any viable computer programs?"

"Yes. One."

Asher felt his interest suddenly spike. "Really?"

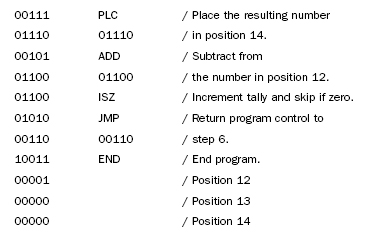

"A program for a simple mathematical expression. Here it is." Marris punched another key, and a series of instructions appeared on his monitor.

Asher bent eagerly toward it.

"What does the program do?" Asher asked.

"You'll notice that it's written as a series of repeated subtractions, coded in a loop. That's the way you do division in machine language: by repeated subtraction. Well, it's one way-you could also do an arithmetic shift right-but that would require a more specialized computing system."