The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Once more, to my father,

Dewey W. Lambdin, Lt. Cmdr., USN

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

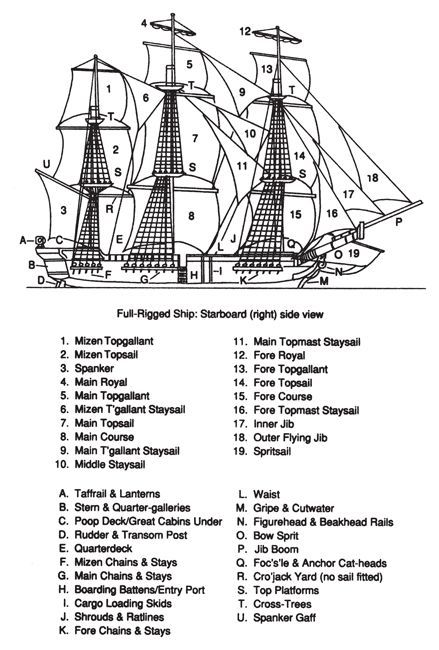

Full-rigged ship diagram

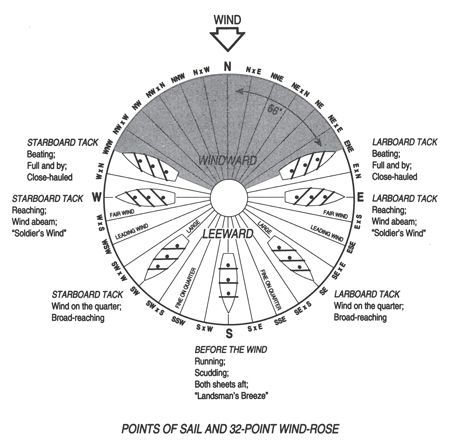

Points of sail diagram

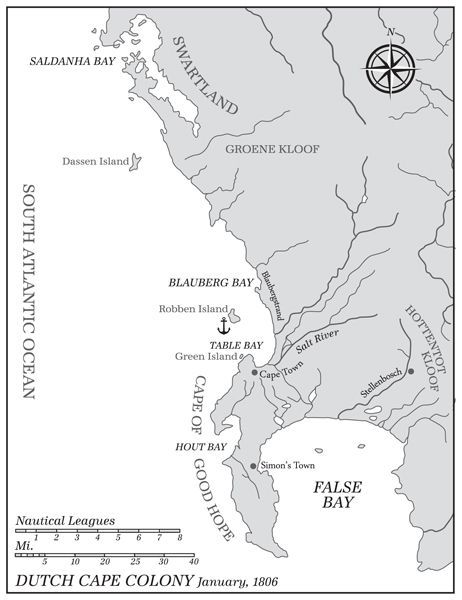

Map of Dutch Cape Colony

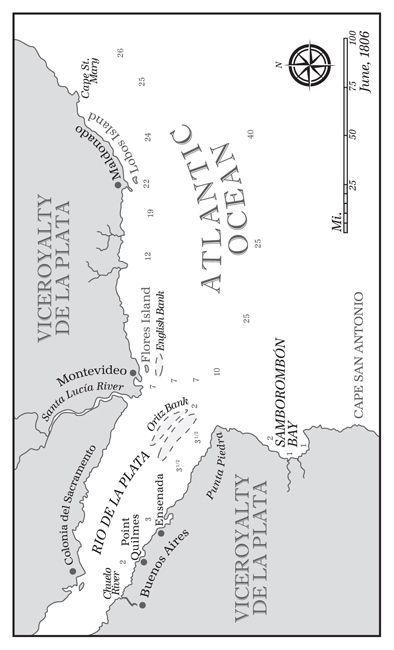

Map of South America

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Book One

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Book Two

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Book Three

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Book Four

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Afterword

Also by Dewey Lambdin

About the Author

Copyright

PROLOGUE

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

Leash’d in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire

Crouch for employment.

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE,

T HE L IFE OF K ING

HENRYTHEFIFTH,

PRO., 5–8

CHAPTER ONE

A jaunt ashore would clear his head and provide a brief but welcome diversion from his new responsibility and worry, he was sure of it. It might even result in a dalliance with a young, bored, and attractive “grass widow”, he most certainly hoped!

Captain Sir Alan Lewrie, Baronet (a title he still found quite un-believable and un-earned), left his frigate, HMS Reliant, round mid-morning to be rowed ashore in one of the twenty-five-foot cutters that had replaced his smaller gig, turned out in his best uniform, less the star and sash of his Knighthood in the Order of The Bath, an honour he also felt un-earned, scrubbed up fresh and sweet-smelling, shaved closely, and with fangs polished and breath freshened with a ginger-flavoured pastille. His ship was safely anchored in West Bay of Nassau Harbour, protected by the shore forts, and the weather appeared fine despite the fact that it was prime hurricane season in the Bahamas.

The man’s a fool, Lewrie told himself; an old “colt’s tooth” more int’rested in wealth than in his young wife, so he deserves whatever he gets.

The husband in question was in his early fifties, rich enough already, but was off for the better part of the month to the salt works on Grand Turk, far to the South. He was also dull, bland, strict, and abstemious with few social graces, or so Lewrie had found him the two times they’d met at civilian doings ashore.

Captain Alan Lewrie, in contrast, was fourty-two, much slimmer at twelve stone, and had a full head of slightly curly mid-brown hair, bleached lighter at the sides where his hat did not shield it, and was reckoned merrily handsome and trim.

Lewrie had also been a widower for nigh three years, since the summer of 1802, and that fact would set the “chick-a-biddy” matrons to chirping in welcome, in hopes of “buttock-brokering” one of their semi-beautiful daughters off to someone with income and prospects. He was, in short, one reckoned a “catch”, a naval hero.

Admittedly, despite the “heroic” part, Lewrie was also reckoned a tad infamous; he’d been the darling of Wilberforce, Hannah More, and the Abolitionists dedicated to the elimination of Negro slavery in the British Empire, and had stood trial in King’s Bench in London for the liberation (some critics would say criminal theft!) of a dozen Black slaves on Jamaica to man his previous frigate, ravaged by Yellow Jack and dozens of hands short. In point of fact, Lewrie was against the enslavement of Negroes, or anyone else, but was not so foolish as to crow it to the rooftops, or turn boresome on the subject. His repute was titillating, but not so sordid or infamous that he did not make a fine house guest.

The lady in question … Lewrie recalled that she seemed amenable to his previous gallantries, and how she slyly pouted and rolled her eyes when her “lawful blanket” prosed on about something boresome, and how she rewarded Lewrie’s teasing jollities, and a double entendre or two, with smiles, a twinkle in her eyes, and some languid come-hither flourishes of her fan.

Perhaps this would be the day to see if he would “get the leg over”! Such was becoming most needful, to do the “needful”.

Lewrie felt a twinge of conscience (a wee’un) as he thought of Lydia Stangbourne, his … dare he call her his lady love?… far off in England. But, Lydia was thousands of miles and at least two months away at that moment, and both had agreed that their relationship was still “early days”; no promises had been made by either, no plighting of troths or exchanges of gifts of consequence. On their last night at the George Inn at Portsmouth before he’d taken Reliant to sea, she had laughed off the very idea of marrying him, or anyone else, again, after the bestial nature of her first husband, and the scandal which had plagued her after her Bill of Divorcement in Parliament had been made public. To all intents and purposes, Lewrie was a free man with … needs.

“Hmmph,” his Cox’n, Liam Desmond, grunted, interrupting Lewrie’s lascivious musings. “Coulda sworn that brig sailed hours ago, sor … th’ one with th’ big white patch in her fore course? But, there she be, goin’ like a coach and four.”

“Aye, she did,” Lewrie agreed, shifting about on the thwart on which he sat for a better look, and wishing for a telescope. The brig had put out a little after dawn, when Lewrie was on the quarterdeck to take the cool morning air as Reliant’s hands had holystoned and mopped the decks. “Did she not go full and by, up the Nor’east Providence Channel? Now, here she is, runnin’ ‘both sheets aft’, bound West.”

The weary-looking old trading brig was not two miles off the harbour entrance, and her large new patch of white canvas on her parchment-tan older fore course sail proved her identity.

“Is them stuns’ls she’s flyin’?” Desmond asked in wonder.

As they watched, a small puff of dirty grey-white gun smoke blossomed on the brig’s shoreward side, followed seconds later by the thin yelp-thump of a gun’s discharge. The many local fishing boats out past the harbour entrance, off Hog Island, saw the shot and they began to put about, too, some headed West as if fleeing to the Berry Islands or Bimini, and some headed back into port in haste.

Oh, mine arse on a band-box, Lewrie thought with a chill in his innards; It’s the bloody French, come at last!