SUGAWARA AKITADA

COMPENDIUM

His noble family fallen on hard times, Sugawara Akitada works as a minor official in the Ministry of Justice in Heian Kyo, capital of Japan in the 11th century. The post is boring, but there are bills to pay, servants to maintain and a diminished estate to keep up as best he can. However, Akitada also has a sharp mind and an inquisitive nature, both of which get put to the test as he unravels murders and mysteries that carry him from the depths of the most common peasant hovels to the sacred halls of the Imperial Palace itself. Bound not only by his sense of decency and honor, but the strict codes and social structure of Ancient Japan, Akitada must step carefully while gathering clues to solve the puzzles before him. About I. J. Parker

I.J. PARKER won the Private Eye Writers of America Shamus Award for Best P.I. Short Story in 2000 for "Akitada's First Case," published in 1999. An Associate Professor of English and Foreign Languages (retired) at a Virginia university, Parker began research into11th century Japan because of a professional interest in that culture's literature. This led to the first Akitada short story, "Instruments of Murder," published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine in October of 1997. Although Parker's multi-lingual background includes a little Japanese, research is done using translations and the help of scholars specializing in the period. She has no agent at the moment.

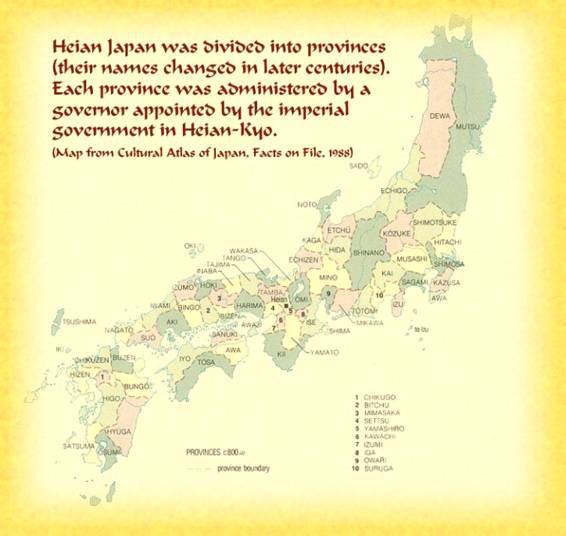

The Heian Period in the history of Japan is often referred to as “the golden age.” It lasted from the 9th through the 12th centuries and preceded the medieval era of shoguns and samurai. The Heian Age was characterized by relative peace and stability and a central government in the capital, Heian-kyo, by an emperor and the court aristocracy. It is the historical background for both the Akitada mystery series (11th century) and the novel The Hollow Reed (12th century).

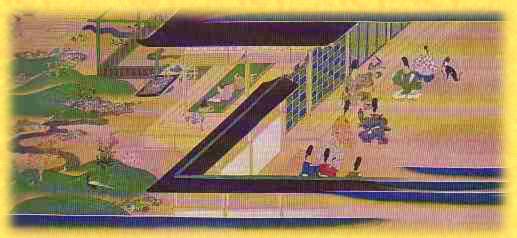

Nobleman's House

Sugawara no Akitada (in Japan, the family name comes before the given name, and the "no" is an obsolete link in noble names) is thought to have been born in 989 A.D. into a family of scholar officials (for his precise parentage, see THE HELL SCREEN). His childhood and early teens were spent in the family mansion in Heian Kyo (the capital of Japan at the time and modern Kyoto) as the only son of a minor functionary in the imperial administration.

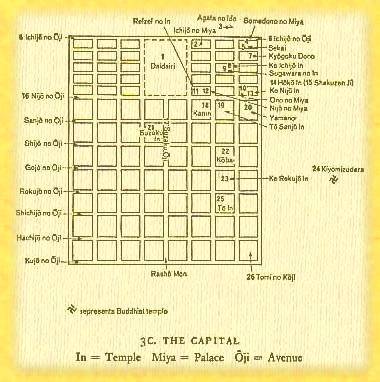

Following in his father's footsteps, he attended the imperial university (for details about university life, see RASHOMON GATE) just south of the Daidairi, or Greater Palace, where his father and hundreds of other nobles worked in the offices of various ministries and bureaus.

Akitada pursued a legal curriculum and placed first in the final examinations. This guaranteed him a position in the government service, and he started his career as a very junior clerk in the Ministry of Law. By this time, his father had died, leaving him the only support for a demanding mother and two younger sisters, a responsibility he will have increasing difficulty with by getting involved in criminal cases that are none of his business and lead to reprimands and even dismissals (see "Akitada's First Case"). The People of Heian Japan:

In Akitada's time only two classes -- nobles and commoners -- existed, but there was also an underclass of "non-persons," the slaves and outcastes. Akitada was born one of the "good people," though he clings rather desperately to the bottom rung of that ladder. Perhaps it is this fact which gives him a greater closeness to and understanding for the less fortunate and causes him to keep breaking rigid social rules to associate with them.

Carriages at the Gate Servants

Those above him in rank are far more powerful nobles, in particular members of the Fujiwara clan, one branch of which (the sekkanke) furnished the chancellors and senior ministers, most of the imperial consorts, and filled many other upper level positions in the central and provincial administrations.

Those below him are peasants, merchants, artisans, and soldiers. Of these, the peasants were the poorest but most highly respected because they fed the nation. The merchants and artisans lived in the cities and sometimes became prosperous, especially if they dealt wholesale in rice, silk, or sake, or if they practiced a valued skill, for example sword making.

Among the slaves and outcastes were entertainers, laborers, and workers in despised trades (for example, butchery, leather-working, or handling the dead. This class originated probably from early prisoners of war, condemned criminals, and natives of the northern territories; it was perpetuated through birth and practice into the present day. Visit to a Shrine Beside the lay population, there was also the clergy which was essentially classless, but had its own ranks. There were Shinto priests and priestesses and Buddhist monks and nuns. Akitada, somewhat uncharacteristically for a nobleman of his period, dislikes and distrusts Buddhism and prefers the native Shinto beliefs. Monks

Since both faiths played an enormous role in the lives of high and low, Buddhist and Shinto clergy were common and visible in society. Shinto priests were attached to Shinto shrines but participated in many public rituals. They could marry, and their functions were often hereditary. Buddhists clergy, who came from all classes, were supposed to be celibate.

Because many noble persons and emperors gave up the “world” in old age or because of serious illness or, in the case of women, because their husbands died, the highest-ranking Buddhist clergy came from the ruling class. Apart from those who lived in monasteries, Buddhist clergy also served as village priests or wandered the roads, begging and preaching. Towards the end of the Heian age, large monasteries became increasingly warlike, maintained armies of warrior monks, attacked rival institutions, and took sides in secular politics. Akitada encounters warrior monks in THE DRAGON SCROLL. The Ancient Capital

During Akitada’s time, the capital of Japan was Heian Kyo, the modern Kyoto. Founded in 794, it remained the capital until the 13th century and the seat of the emperor until 1869.

fromIvanMorris,ThePillowbookofSeiShonagon In plan, the capital was very similar to the great Chinese capitals like Chang-An, and followed the Chinese belief that cities needed three mountains nearby – to the north, west, and south. They also needed rivers to the west and east, and a large pond to the south. The reasons for these geographic features were based on fears of evil influences which could approach a city from all sides. Beyond these considerations, the layout of Heian Kyo followed strict rules of order. It was to be rectangular, bisected by a major north-south avenue, intersected at precise distances by north-south and east-west roads forming a grid pattern, and the seat of government had to occupy the northernmost center, forming a walled rectangular imperial city within the capital. Such orderliness of planning pervaded much of the political thought of the time, and Akitada is thoroughly versed in the teachings of Confucian order and harmony. He strongly disapproves of disorder.