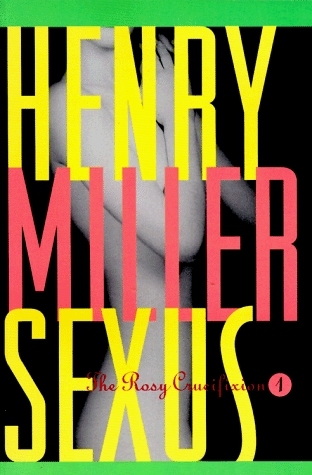

The Rosy Crucifixion 1

Sexus

VOLUME ONE

1

It must have been a Thursday night when I met her for the first time—at the dance hall. I reported to work in the morning, after an hour or two's sleep, looking like a somnambulist. The day passed like a dream. After dinner I fell asleep on the couch and awoke fully dressed about six the next morning. I felt thoroughly refreshed, pure at heart, and obsessed with one idea—to have her at any cost. Walking through the park I debated what sort of flowers to send with the book I had promised her (Winesburg, Ohio). I was approaching my thirty-third year, the age of Christ crucified. A wholly new life lay before me, had I the courage to risk all. Actually there was nothing to risk: I was at the bottom rung of the ladder, a failure in every sense of the word.

It was a Saturday morning, then, and for me Saturday has always been the best day of the week. I come to life when others are dropping off with fatigue; my week begins with the Jewish day of rest. That this was to be the grand week of my life, to last for seven long years, I had no idea of course. I knew only that the day was auspicious and eventful. To make the fatal step, to throw everything to the dogs, is in itself an emancipation: the thought of consequences never entered my head. To make absolute, unconditional surrender to the woman one loves is to break every bond save the desire not to lose her, which is the most terrible bond of all.

I spent the morning borrowing right and left, dispatched the book and flowers, then sat down to write a long letter to be delivered by a special messenger. I told her that I would telephone her later in the afternoon. At noon I quit the office and went home. I was terribly restless, almost feverish with impatience. To wait until five o'clock was torture. I went again to the park, oblivious of everything as I walked blindly over the downs to the lake where the children were sailing their boats. In the distance a band was playing; it brought back memories of my childhood, stifled dreams, longings, regrets. A sultry, passionate rebellion filled my veins. I thought of certain great figures in the past, of all that they had accomplished at my age. What ambitions I may have had were gone; there was nothing I wanted to do except to put myself completely in her hands. Above everything else I wanted to hear her voice, know that she was still alive, that she had not already forgotten me. To be able to put a nickel in the slot every day of my life henceforth, to be able to hear her say hello, that and nothing more was the utmost I dared hope for. If she would promise me that much, and keep her promise, it wouldn't matter what happened.

Promptly at five o'clock I telephoned. A strangely sad, foreign voice informed me that she was not at home. I tried to find out when she would be home but I was cut off. The thought that she was out of reach drove me frantic. I telephoned my wife that I would not be home for dinner. She greeted the announcement in her usual disgusted way, as though she expected nothing more of me than disappointments and postponements. «Choke on it, you bitch,» I thought to myself as I hung up, «at least I know that I don't want you, any part of you, dead or alive.» An open trolley was coming along; without a thought of its direction I hopped aboard and made for the rear seat. I rode around for a couple of hours in a deep trance; when I came to I recognized an Arabian ice cream parlor near the water-front, got off, walked to the wharf and sat on a string-piece looking up at the humming fret-work of the Brooklyn Bridge. There were still several hours to kill before I dared venture to go to the dance hall. Gazing vacantly at the opposite shore my thoughts drifted ceaselessly, like a ship without a rudder.

When finally I picked myself up and staggered off I was like a man under an anaesthetic who has managed to slip away from the operating table. Everything looked familiar yet made no sense; it took ages to coordinate a few simple impressions which by ordinary reflex calculus would mean table, chair, building, person. Buildings emptied of their automatons are even more desolate than tombs; when the machines are left idle they create a void deeper than death itself. I was a ghost moving about in a vacuum. To sit down, to stop and light a cigarette, not to sit down, not to smoke, to think, or not to think, breathe or stop breathing, it was all one and the same. Drop dead and the man behind you walks over you; fire a revolver and another man fires at you; yell and you wake the dead who, oddly enough, also have powerful lungs. Traffic is now going East and West; in a minute it will be going North and South. Everything is proceeding blindly according to rule and nobody is getting anywhere. Lurch and stagger in and out, up and down, some dropping out like flies, others swarming in like gnats. Eat standing up, with slots, levers, greasy nickels, greasy cellophane, greasy appetite. Wipe your mouth, belch, pick your teeth, cock your hat, tramp, slide, stagger, whistle, blow your brains out. In the next life I will be a vulture feeding on rich carrion: I will perch on top of the tall buildings and dive like a shot the moment I smell death. Now I am whistling a merry tune—the epigastric regions are at peace. Hello, Mara, how are you? And she will give me the enigmatic smile, throwing her arms about me in warm embrace. This will take place in a void under powerful Klieg lights with three centimeters of privacy marking a mystic circle about us.

I mount the steps and enter the arena, the grand ball-room of the double-barrelled sex adepts, now flooded with a warm boudoir glow. The phantoms are waltzing in a sweet chewing gum haze, knees slightly crooked, haunches taut, ankles swimming in powdered sapphire. Between drum beats I hear the ambulance clanging down below, then fire engines, then police sirens. The waltz is perforated with anguish, little bullet holes slipping over the cogs of the mechanical piano which is drowned because it is blocks away in a burning building without fire escapes. She is not on the floor. She may be lying in bed reading a book, she may be making love with a prize-fighter, or she many be running like mad through a field of stubble, one shoe on, one shoe off, a man named Corn Cob pursuing her hotly. Wherever she is I am standing in complete darkness; her absence blots me out.

I inquire of one of the girls if she knows when Mara will arrive. Mara? Never heard of her. How should she know anything about anybody since she's only had the job an hour or so and is sweating like a mare wrapped in six suits of woolen underwear lined with fleece. Won't I offer her a dance—she'll ask one of the other girls about this Mara. We dance a few rounds of sweat and rose-water, the conversation running to corns and bunions and varicose veins, the musicians peering through the boudoir mist with jellied eyes, their faces spread in a frozen grin. The girl over there, Florrie, she might be able to tell me something about my friend. Florrie has a wide mouth and eyes of lapis lazuli; she's as cool as a geranium, having just come from an all-afternoon fucking fiesta. Does Florrie know if Mara will be coming soon? She doesn't think so... she doesn't think she'll come at all this evening. Why? She thinks she has a date with some one. Better ask the Greek—he knows everything.

The Greek says yes, Miss Mara will come... yes, just wait a while. I wait and wait. The girls are steaming, like sweating horses standing in a field of snow. Midnight. No sign of Mara. I move slowly, unwillingly, towards the door. A Porto Rican lad is buttoning his fly on the top step.