The crusaders nonetheless had one advantage: Muslim Syria was in a parlous state of disarray. Riven by power struggles since the collapse of Seljuq unity in the early 1090s, the region’s Turkish potentates were more interested in pursuing their own petty infighting than in offering any form of rapid or concerted Islamic response to this unexpected Latin incursion. The two young feuding brothers Ridwan and Duqaq ruled the major cities of Aleppo and Damascus, but were locked in a civil war. Antioch itself was governed as a semi-autonomous frontier settlement of the faltering Seljuq sultanate of Baghdad by Yaghi Siyan, a conniving, white-haired Turkish warlord. He commanded a well-provisioned garrison of perhaps 5,000 troops, enough to man the city’s defences but not sufficient to repel the crusaders in open battle. His only option was to trust in Antioch’s fortifications and hope to survive the advent of the crusade. As the Franks approached he dispatched appeals for aid to his Muslim neighbours in Aleppo and Damascus, as well as to Baghdad itself, in the hope of attracting reinforcement. He also trained a watchful eye on the many Greek, Armenian and Syrian Christian members of Antioch’s cosmopolitan population, wary of betrayal from within.

The City of Antioch

A WAR OF ATTRITION

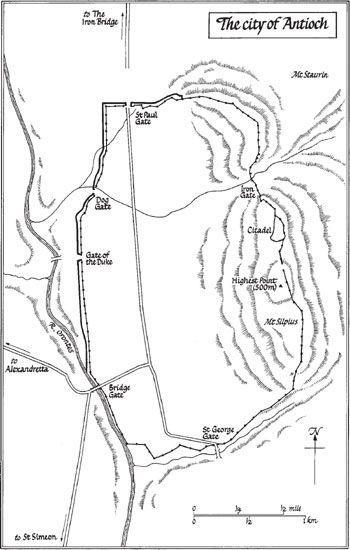

Upon their arrival, the Latins had to decide upon a strategy. Discouraged by the massive scale of Antioch’s fortifications and lacking the craftsmen and materials required to build weapons of assault siege warfare–scaling ladders, mangonels or movable towers–they quickly recognised that they were in no position to storm its battlements. But, as at Nicaea, an attrition siege presented difficulties. The sheer length of Antioch’s walls, the rugged topography of the enclosing mountains and the presence of no fewer than six main gateways leading out of the city made a full encirclement virtually impossible. As it was, a council of princes decided upon a strategy of partial blockade, and in the last days of October their armies took up positions before the city’s three north-western gates. As time went on the crusaders sought to police access to Antioch’s two southern entrances. A temporary bridge was built across the Orontes to facilitate access to the south, and a series of makeshift siege forts developed to tighten the noose. But one entrance remained, the Iron Gate–perched in a rocky gorge between Staurin and Silpius, out of the crusaders’ reach. Unguarded, it offered Yaghi Siyan and his men a crucial lifeline to the outside world throughout the long months that followed.

From the autumn of 1097 onwards the Franks committed themselves to the grinding reality of a medieval encirclement siege. The day-to-day business of this form of warfare might involve frequent small-scale skirmishing, but in essence depended not upon a battle of arms, but rather upon a test of physical and psychological endurance. For both the Latins and their Muslim foes morale was critical, and each side readily employed an array of gruesome tactics to erode their opponent’s mental resilience. After winning a major battle in early 1098 the crusaders decapitated more than one hundred Muslim dead, stuck their heads upon spears and gleefully paraded them before the walls of Antioch ‘to increase the Turks’ grief’. Following another skirmish the Muslims stole out of the city at dawn to bury their dead, but, according to one Latin eyewitness, when the Christians discovered this:

They ordered the bodies to be dug up and the tombs destroyed, and the dead men dragged out of their graves. They threw all the corpses into a pit, and cut off their heads and brought them to our tents. When the Turks saw this they were very sad and grieved almost to death, they lamented every day and did nothing but weep and howl.

For his part, Yaghi Siyan ordered the public victimisation of Antioch’s indigenous Christian population. The Greek patriarch, who had long resided peacefully within the city, was now dangled by his ankles from the battlements and beaten with iron rods. One Latin recalled that ‘many Greeks, Syrians and Armenians, who lived in the city, were slaughtered by the maddened Turks. With the Franks looking on, they threw outside the walls the heads of those killed with their catapults and slings. This especially grieved our people.’ Crusaders taken prisoner often suffered similar maltreatment. The archdeacon of Metz was caught ‘playing a game of dice’ with a young woman in an orchard near the city. He was beheaded on the spot, while she was taken back to Antioch, raped and killed. The following morning, both of their heads were catapulted into the Latin camp.

Alongside these malicious exchanges, the siege revolved around a struggle for resources. This grim waiting game, in which each side sought to outlast the other, depended upon supplies of manpower, materials and, most fundamentally of all, food. With logistical considerations paramount, the crusaders were in the weaker position. The incomplete blockade meant that the Muslim garrison could still access external resources and aid. The larger crusading army, however, rapidly denuded their immediate resources and had to range ever further afield into hostile territory in pursuit of provisions. As the campaign continued, harsh winter weather compounded the situation. In a letter to his wife, the Frankish prince Stephen of Blois complained: ‘Before the city of Antioch, throughout the whole winter we suffered for our Lord Christ from excessive cold and enormous torrents of rain. What some say about the impossibility of bearing the heat of the sun throughout Syria is untrue, for the winter there is very similar to our winter in the West.’ One contemporary Armenian Christian later recalled that, in the depths of that terrible winter, ‘because of the scarcity of food, mortality and affliction fell upon the Frankish army to such an extent that one out of five perished and all the rest felt themselves abandoned and far from their homeland’.22

The suffering in the Frankish camp reached its height in January 1098. Hundreds, perhaps even thousands, perished, weakened by malnourishment and illness. It was said that the poor were reduced to eating ‘dogs and rats…the skins of beasts and seeds of grain found in manure’. Bewildered by this desperate predicament, many began to question why God had abandoned the crusade, His sacred venture. Amidst an increasingly malevolent atmosphere of suspicion and recrimination, the Latin clergy proffered an answer: the expedition had become tainted by sin. To combat this pollution, the papal legate Adhémar of Le Puy prescribed a succession of purgative rituals–fasting, prayer, almsgiving and procession. Women, the supposed repositories of impurity, were simultaneously expelled from the camp. In spite of these measures, many Christians fled northern Syria, preferring an uncertain journey back to Europe over the appalling conditions at the siege. Even the demagogue Peter the Hermit, once the impassioned mouthpiece of crusading fervour, tried to desert. Caught attempting to escape under cover of night, he was unceremoniously dragged back by Tancred. Around the same time, the crusaders’ Greek guide Taticius left the expedition, apparently in search of reinforcements and provisions in Asia Minor. He never returned, but the Byzantines on Cyprus did send some supplies to the Franks outside Antioch.

A hardened core of crusaders survived the manifold privations of that bitter winter and, with the arrival of spring, the balance of the siege began to shift slowly in their favour. The system of foraging centres established by the Franks played a part in easing the situation at Antioch: resources arrived from as far afield as Cilicia and, later, from Baldwin of Boulogne at Edessa. More significant still was aid transported across the Mediterranean and siphoned through the northern Syrian ports of Latakia and St Simeon, which the Latins had now occupied. On 4 March a small fleet of English ships arrived at the harbour of St Simeon, carrying food, building materials and craftsmen. A few days later, Bohemond and Raymond of Toulouse successfully escorted this valuable cargo back from the coast in the face of heavy opposition from Antiochene Muslim troops. The resultant influx of materials allowed the Franks to close a key loophole in their investment.