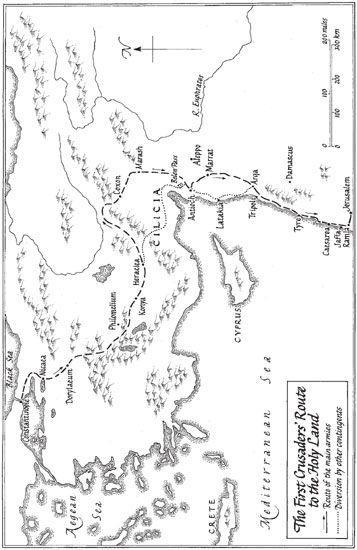

The First Crusaders’ Route to the Holy Land

The siege of Nicaea

The main armies of the First Crusade started to gather on the shore of Asia Minor in February 1097, and over the following months their numbers gradually built up to perhaps 75,000, including some 7,500 fully armed, mounted knights and a further 35,000 lightly equipped infantry. The timing of their arrival on the doorstep of the Muslim world proved to be most propitious. Months earlier Kilij Arslan, the Seljuq Turkish sultan of the region, had annihilated the People’s Crusade with relative ease. Thinking that this second wave of Franks would pose a similarly limited danger, he set off to deal with a minor territorial dispute far to the east. This blunder left the Christians free to cross the Bosphorus and establish a beachhead without hindrance throughout that spring.

The Latins’ first Muslim target was defined by their alliance with the Greeks, and Alexius’ primary objective was Nicaea, the city just inland from the Bosphorus which Kilij Arslan had brazenly declared his capital. This Turkish foothold in western Asia Minor threatened the security of Constantinople itself, but it had stubbornly resisted the emperor’s best efforts at reconquest. Now Alexius deployed his new weapon: the ‘barbarian’ Franks. They arrived at Nicaea on 6 May to find an imposing stronghold. One Latin eyewitness described how ‘skilful men had enclosed the city with such lofty walls that it feared neither the attack of enemies nor the force of any machine’. These thirty-foot-high battlements, nearly three miles in circumference, incorporated more than one hundred towers. More troubling still was the fact that the western edge of the city was built against the shores of the massive Askanian Lake, thus allowing the Turkish garrison, which probably numbered no more than a few thousand, to receive supplies and reinforcements even if they were encircled on land.

The Christians came close to suffering a damaging reversal in the first stage of their siege. Having now recognised the threat to his capital, Kilij Arslan returned from eastern Asia Minor in late spring. On 16 May he tried to launch a surprise attack upon the armies ranged before Nicaea, pouring out from the steep, wooded hills to the south of the city. Luckily for the Franks, a Turkish spy caught in their camp betrayed the Seljuqs’ plans when threatened with torture and death. When the Muslim assault began the Latins were ready and, through sheer weight of numbers, soon forced Kilij Arslan to retreat. He escaped with most of his army intact, but his military prestige and the morale of Nicaea’s garrison suffered grave damage. Hoping to accentuate enemy desperation, the crusaders decapitated hundreds of Turkish dead, parading the heads upon spikes before the city and even throwing some over the walls ‘in order to cause more terror’. This sort of barbarous psychological warfare was common in medieval sieges and certainly not the preserve of the Christians. In the coming weeks the Nicaean Turks retaliated with macabre tenacity, using iron hooks attached to ropes to haul up any Frankish corpses left near the walls after skirmishes and then hanging these cadavers from the walls to rot, so as ‘to offend the Christians’.14

Having repulsed Kilij Arslan’s attack, the crusaders adopted a combined siege strategy to overcome Nicaea’s defences, employing two styles of siege warfare simultaneously. On one hand, they established a close blockade of the city’s landward walls to the north, east and south, hoping to cut off Nicaea from the outside world, gradually grinding its garrison into submission through physical and psychological isolation. As yet, however, the Franks had no means of severing westward lines of communication via the lake, so they also actively pursued the more aggressive strategy of an assault siege. Early attempts to storm the city with scaling ladders failed, so efforts centred upon creating a physical breach in the walls. The crusaders built some stone-throwing machines, or mangonels, but these were of limited power, incapable of propelling missiles of sufficient size to inflict significant damage to robust battlements. Instead, the Latins used light bombardment to harass the Turks and, under cover of this fire, attempted to undermine Nicaea’s walls by hand.

This was potentially lethal work. To reach the foot of the ramparts troops had to negotiate a deadly rain of Muslim arrows and stone missiles, and, once there, they were exposed to attack from above by burning pitch and oil. The Franks experimented with a range of portable bombardment screens to counter these dangers, with varying degrees of success. One such contraption, proudly christened ‘the fox’ and fashioned from oak beams, promptly collapsed, killing twenty crusaders. The southern French had more luck, constructing a sturdier, sloping-roofed screen which allowed them to reach the walls and begin a siege mine. Sappers dug a tunnel beneath the southern battlements, carefully buttressing the excavation with timber supports as they went, before packing the void with branches and kindling. At dusk around 1 June 1097 they set this wood alight, leaving the whole structure to collapse, bringing down a small section of the defences above. Unfortunately for the Franks, the Turkish garrison managed to repair the damage overnight and no further progress was made.

By mid-June, with the crusaders enjoying no noteworthy progress, it fell to the Byzantines to tip the balance. Stationed a day’s journey to the north, Alexius had maintained a discreet but watchful distance from the siege, while dispatching troops and military advisers to assist the Latins. Most notable among these was Taticius, a cool-headed veteran of the imperial household born of half-Arab, half-Greek parentage, known for his loyalty to the emperor.* It was not until mid-June that Alexius made the defining contribution to Nicaea’s investment. In response to requests from the crusader princes, he portaged a small fleet of Greek ships twenty miles overland to the Askanian Lake. At dawn on 18 June this flotilla sailed towards Nicaea’s western walls, trumpets and drums blaring, as the Franks launched a coordinated land-based assault. Utterly horrified, with the noose closing around them, the Seljuq troops within were said to have been ‘afraid almost to death, and began to wail and lament’. Within hours they sued for peace and Taticius and the Byzantines took possession of the city.

The capture of Nicaea marked the high point of Greco-Frankish cooperation during the First Crusade. There were some initial grumbles among the Latin rank-and-file about the lack of plunder, but these were soon silenced by Alexius’ decision to reward his allies with lavish quantities of hard cash. Later western chronicles played up the degree of tension present after Nicaea’s fall, but a letter written home by the leading crusader Stephen of Blois later that same summer made it clear that an atmosphere of friendship and cooperation endured. The emperor now held an audience with the Frankish princes to discuss the next stage of the campaign. The crusaders’ route across Asia Minor was likely agreed and the city of Antioch identified as an objective. Alexius’ plan was to follow in the expedition’s wake, mopping up any territory it conquered and, in the hope of maintaining control over events, he directed Taticius to accompany the Latins as his official representative, along with a small force of Byzantine troops.

Throughout that spring and summer Alexius furnished the Latins with invaluable advice and intelligence. Anna Comnena noted that Alexius ‘warned [them] about the things likely to happen on their journey [and] gave them profitable advice. They were instructed in the methods normally used by the Turks in battle; told how they should draw up a battle-line, how to lay ambushes; advised not to pursue far when the enemy ran away in flight.’ He also counselled the crusade leadership to temper blunt aggression towards Islam with an element of pragmatic diplomacy. They followed his advice, seeking to exploit Muslim political and religious disunity by dispatching envoys by ship to the Fatimid caliphate in Egypt to discuss a potential treaty.15