The Crusades

The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land

Thomas Asbridge

For my father

Gerald Asbridge

Contents

List of Maps

Introduction

Part I: The Coming of the Crusades

1 Holy War, Holy Land

2 Syrian Ordeals

3 The Sacred City

4 Creating the Crusader States

5 Outremer

6 Crusading Reborn

Part II: The Response of Islam

7 Muslim Revival

8 The Light of Faith

9 The Wealth of Egypt

10 Heir or Usurper

11 The Sultan of Islam

12 Holy Warrior

Part III: The Trial of Champions

13 Called to Crusade

14 The Conqueror Challenged

15 The Coming of Kings

16 Lionheart

17 Jerusalem

18 Resolution

Part IV: The Struggle for Survival

19 Rejuvenation

20 New Paths

21 A Saint at War

Part V: Victory in the East

22 Lion of Egypt

23 The Holy Land Reclaimed

Conclusion

The Legacy of the Crusades

Acknowledgements

Chronology

Notes

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Other Books by Thomas Asbridge

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

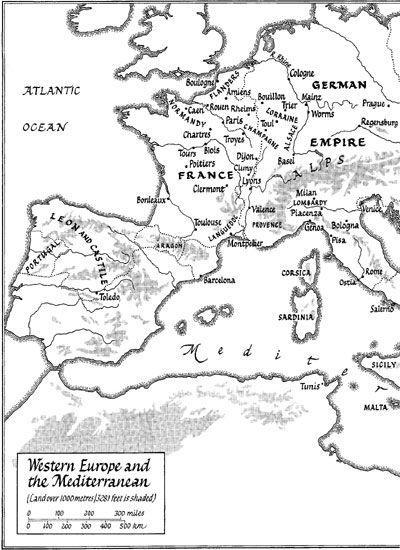

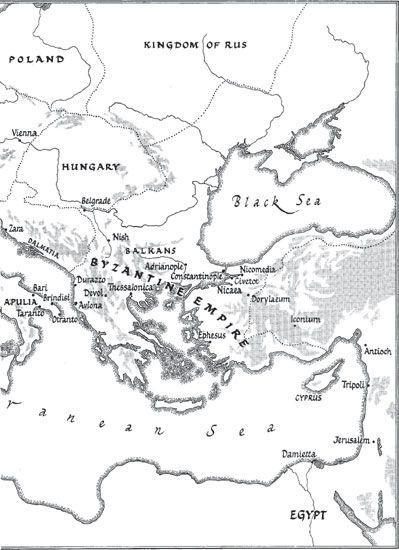

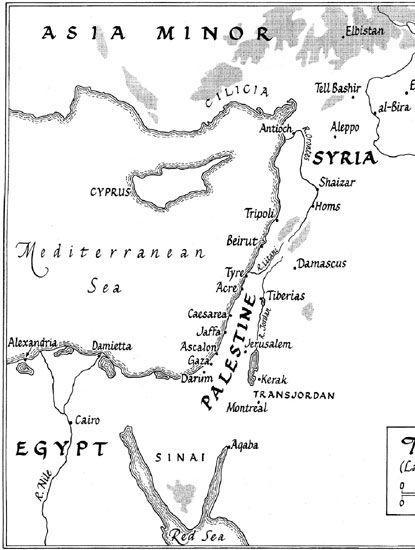

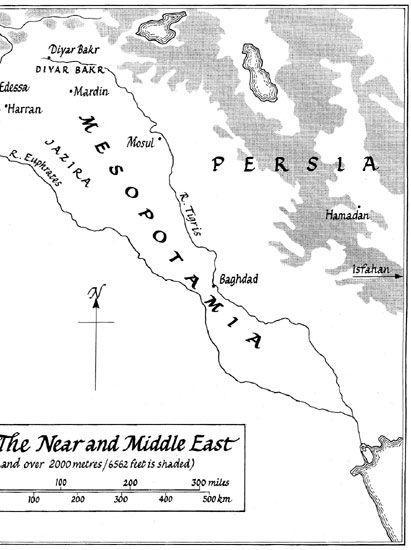

LIST OF MAPS

Western Europe and the Mediterranean

The Near and Middle East

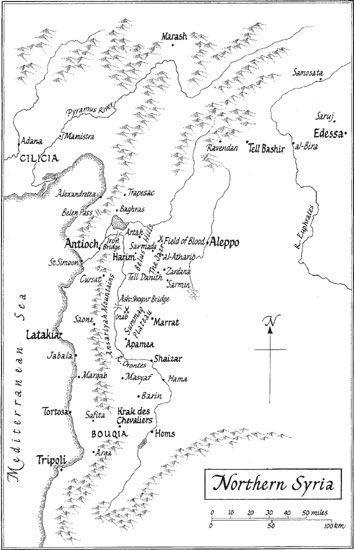

Northern Syria

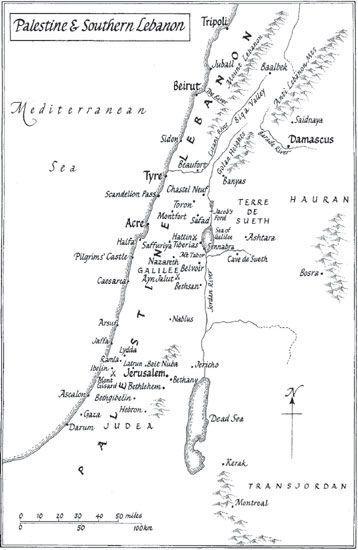

Palestine and Southern Lebanon

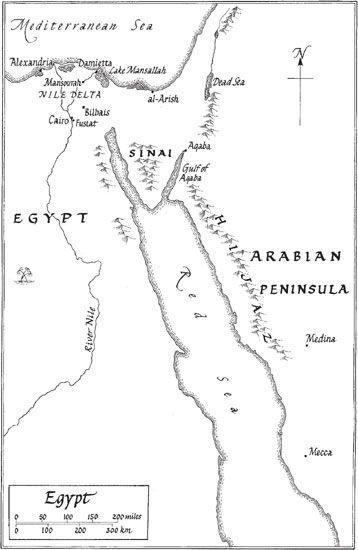

Egypt

The First Crusaders’ Route to the Holy Land

The City of Antioch

The City of Jerusalem

The Crusader States in the Early Twelfth Century

Saladin’s Hattin Campaign

The Siege of Acre during the Third Crusade

Richard the Lionheart’s March from Acre to Jaffa

The Third Crusade: Paths to Jerusalem

The Crusader States in the Early Thirteenth Century

The Nile Delta

Mamluks and Mongols in 1260

Western Europe and the Mediterranean

The Near and Middle East

Northern Syria

Palestine and Southern Lebanon

Egypt

INTRODUCTION

THE WORLD OF THE CRUSADES

Nine hundred years ago the Christians of Europe waged a series of holy wars, or crusades, against the Muslim world, battling for dominion of a region sacred to both faiths–the Holy Land. This bloody struggle raged for two centuries, reshaping the history of Islam and the West. In the course of these monumental expeditions, hundreds of thousands of crusaders travelled across the face of the known world to conquer and then defend an isolated swathe of territory centred on the hallowed city of Jerusalem. They were led by the likes of Richard the Lionheart, warrior-king of England, and the saintly monarch of France, Louis IX, to fight in gruelling sieges and fearsome battles; passing through verdant forests and arid deserts, enduring starvation and disease, encountering the fabled emperors of Byzantium and marching beside forbidding Templar knights. Those who died were thought of as martyrs, while survivors believed that their souls had been scourged of sin by the tempest of combat and trials of pilgrimage.

The advent of these crusades stirred Islam to action, reawakening dedication to the cause of jihad (holy war). Muslims from Syria, Egypt and Iraq fought to drive their Christian foes out of the Holy Land–championed by the merciless warlord Zangi and the mighty Saladin; empowered by the rise of Sultan Baybars and his elite mamluk slave soldiers; sometimes aided by the intrigues of the implacable Assassins. Years of conflict inevitably bred greater familiarity, even at times grudging respect and peaceful contact through truce and commerce. But as the decades passed, the fires of conflict burned on and the tide slowly turned in Islam’s favour. Though the dream of Christian victory lived on, the Muslim world prevailed, securing lasting possession of Jerusalem and the Near East.

This dramatic story has always fired the imagination and fuelled debate. And, over the centuries, the crusades have been subject to startlingly varied interpretations: held up as proof of the folly of religious faith and the base savagery of human nature, or promoted as glorious expressions of Christian chivalry and civilising colonialism. They have been presented as a dark episode in Europe’s history–when ravening hordes of greedy western barbarians launched unprovoked, acquisitive attacks upon the cultured innocents of Islam–or defended as just wars sparked by Muslim aggression and prosecuted to recover Christian territory. The crusaders themselves have been depicted as both land-hungry brutes and pilgrim soldiers inspired by fervent piety; and their Muslim rivals portrayed as vicious and tyrannical oppressors, ardent fanatics or devout paragons of honour and clemency.

The medieval crusades have also been used as a mirror to the modern world, both through the forging of tenuous links between recent events and the distant past, and via the dubious practice of historical parallelism. Thus, during the nineteenth century the French and English appropriated the memory of the crusades to affirm their imperial heritage; while the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have witnessed a deepening tendency within some sections of the Muslim world to equate modern political and religious struggles with holy wars witnessed nine centuries earlier.

This book explores the history of the crusades from both the Christian and Muslim perspectives–focusing, in particular, upon the contest for control of the Holy Land–and examines how medieval contemporaries experienced and remembered the crusades.* It draws upon the wonderfully rich mine of available written evidence (or primary sources) from the Middle Ages: the likes of chronicles, letters and legal documents, poems and songs; recorded in languages as diverse as Latin, Old French, Arabic, Hebrew, Armenian, Syriac and Greek. Beyond these texts, the study of material remains–from imposing castles to delicate manuscript art and minuscule coins–has thrown new light on the crusading era. Throughout, original research has been informed by the great outpouring of modern scholarship in the field witnessed over the past fifty years.1