* * *

The hunt intensified even with the capture of Doc and special agents quickly descended on the town of Ocala and began an extensive investigation, believing that the map found in Chicago indicated the whereabouts of other Barker-Karpis gang members. Their hunch was right and they soon learned that Fred and Ma were living in a remote cottage located on Lake Weir at Ocklawaha, Florida. At 5:30 a.m. on the morning of January 16, 1935, special agents surrounded the cottage and told Fred and Ma to surrender. No answer or movement was detected for nearly fifteen minutes, and then finally the voice of Ma Barker was heard shouting: “all right, go ahead.” This was interpreted as indicating that they were going to surrender, but still no one emerged from the cottage. Seconds later the true meaning of the message was clear – the agents were forced to take cover under an intense bombardment of machine gun fire. The agents returned fire with a heavy barrage of machine gun rounds, rifle shots and tear gas grenades, and finally everything became quite.

FBI agents waited for nearly an hour before entering the bullet-riddled gang hideout. When they went in, they found Ma Barker dead with a machine gun lying by her left hand, and Fred spread out on the floor next to the window, dead from multiple bullet wounds. He was still clutching a .45 caliber pistol. In the aftermath of the shootout, agents discovered a small arsenal of weapons and nearly $14,000 in large bills. The bodies of Fred and Kate (Ma) Barker would remain unburied from January 16, 1935 until October 1 st, when George Barker finally received assistance for their burial. The two would be laid to rest in a small unknown and unmarked countryside cemetery in Welch, Oklahoma, next to the eldest Barker son Herman.

Agents had also learned that the hideout where Bremer had been held during his kidnapping was in Bensenville, Illinois. Bremer returned to the house and made a positive identification, which would ultimately led to more arrests. Special agents from the FBI continued their search to locate the other fugitives from the Barker-Karpis Gang. Their efforts were successful and they continued to make arrests, including the capture of Volney Davis and Dolores Delaney. Delaney gave birth to a baby boy while in prison, and the child was named Raymond Alvin Karpowicz after his father. The boy was ultimately turned over to Alvin’s mother and father to care for until Dolores was released a few years later.

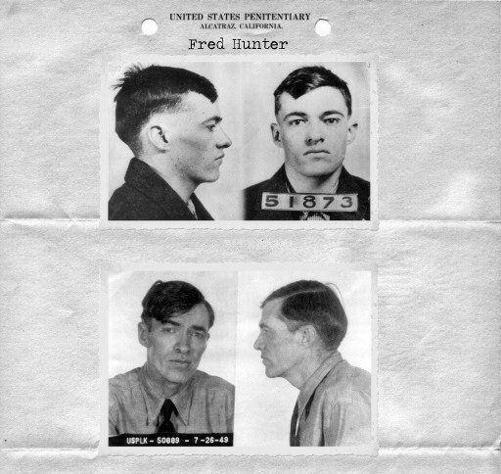

Following the deaths of Fred and Ma Barker, Alvin Karpis would continue his criminal activities with other gangsters. After he and an accomplice returned to Toledo, Ohio, Karpis recruited another underworld figure and future resident of Alcatraz, Freddie Hunter. Karpis, Hunter and some other gang members pulled off a few more successful robberies, including a railroad station heist in which they made off with $34,000 in cash and nearly $12,000 in U.S. Treasury Bonds. It was reported that Freddie Hunter held the station’s mail clerk at gunpoint with a Thompson machine gun, while Karpis and the others gathered up the money. Hunter was later identified as the driver of the gang’s getaway car.

Freddie Hunter

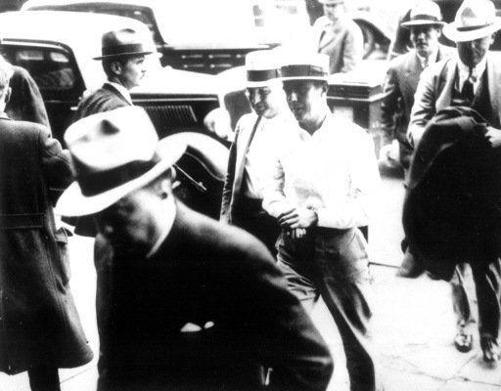

Alvin Karpis is pictured here being apprehended by FBI agents in May of 1936. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (seen in the foreground) he would later claim to have planned the capture and the arrest himself. Karpis would comment that Hoover was “nowhere to be seen” during the arrest, and that he came out only after the suspects were handcuffed.

Meanwhile J. Edgar Hoover had initiated an intense pursuit to capture Karpis and his associate gang members. On May 1, 1936, under Hoover’s personal direction, the FBI descended on Karpis and Hunter in New Orleans. Hoover was on hand to command the squad of FBI agents who performed the arrest. Karpis would later laugh at Hoover’s claim that he had been present for the arrest, stating that Hoover was actually nowhere to be seen until Karpis and his accomplice had already been cuffed, when he quickly emerged for the photo opportunities.

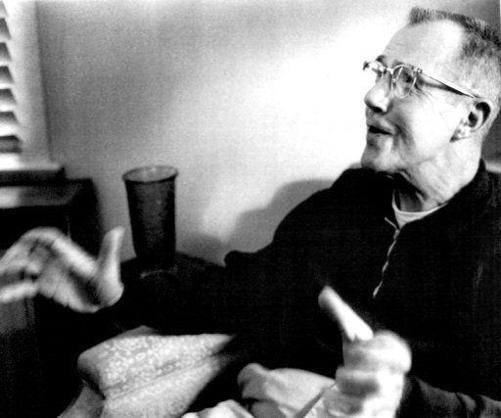

Karpis would not formally participate in the 1939 escape attempt, and would remain at Alcatraz for twenty-five years, the longest term ever served on the Rock. He was sent to McNeil Island in 1962, and finally released in 1969 under condition of deportment to his country of birth, Canada. Karpis would later write two books about his life at Alcatraz, including one bestseller, and he would thus acquire enough funds to fulfill his longtime dream of moving to Spain. His life in Spain is largely undocumented, but on August 26, 1979, Karpis was found dead from what was alleged to be an intentional overdose of sleeping pills. It was speculated that Karpis had likely run out of money, and had no other means to support himself. This was contested by many who knew him, and his death was officially ruled as occurring by natural causes.

Karpis on the day of his release in 1969. Karpis would hold the distinction for the longest single prison term on Alcatraz, nearly 26 years. He would spend a total of 32 years in prison and was finally granted parole on the condition of deportation to his native Canada, from McNeil Island. His lawyer James Carty, later stated that Karpis dreamed of moving to an exotic place where he could escape his past and live his final years in peace. He was estranged from his son Raymond, who had visited him once at Leavenworth (his son died in October of 2001), as well as his only grandson Damon, who died at only 15-years of age. Using money he accumulated from books, interviews and movie rights to his story optioned by Harold Hecht (producer of the Birdman of Alcatraz and other Hollywood greats) for the motion picture The Last Public Enemy (which never made it to production), he moved to Torremolinas, located in Spain’s Costa del Sol. Karpis led a quiet and simple life during his final years. Karpis died in August of 1979 at the age of 71.

A photograph of Alvin Karpis taken during his release from prison in 1969.

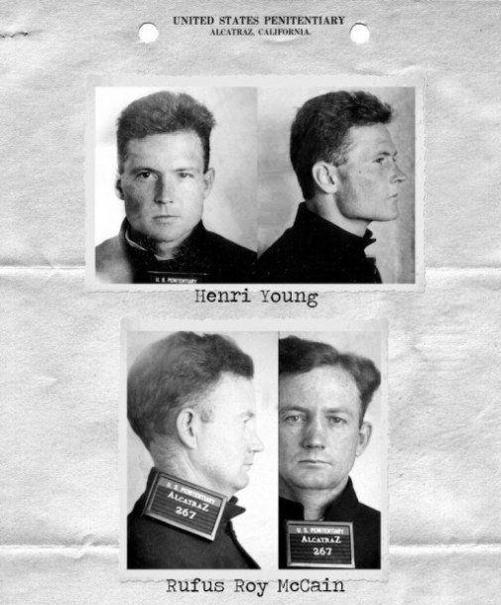

Henri Young and Rufus McCain

Henri Young and Rufus McCain

Two other accomplices in the escape of 1939 were Rufus Roy McCain and Henri Young. Both of their biographies are covered extensively in a separate chapter. Rufus McCain maintained a reputation as a difficult and violence-prone inmate at Alcatraz. He had built a record of violent acts and rebellion against his guards, and therefore he was no stranger to the solitary confinement cells in A and D Blocks.

Henri Young would later become one of the most famous inmates ever to reside on Alcatraz. He would also be the subject of several books and of the Hollywood motion picture Murder in the First, which chronicled the psychological effects of the harsh punishment he allegedly received while imprisoned on the Rock. Like McCain, Young had a long record of outbursts and unusual behavior. He was a problem inmate whose ill-mannered acts would frequently land him in solitary confinement.

William “Ty” Martin

A mug shot series of William “Ty” Martin.

William “Ty” Martin was another accomplice in the escape who had a close association with inmate Bernard Coy, the gang leader of the 1946 “Battle of Alcatraz,” which was debatably the most significant escape attempt ever to take place on the island. Ty was an African-American from Chicago, serving a twenty-five year sentence for armed robbery. He was well liked among the Caucasian inmates, which was unusual as there was heavy racial tension and segregation among prisoners during this period.