Qiu Xiaolong

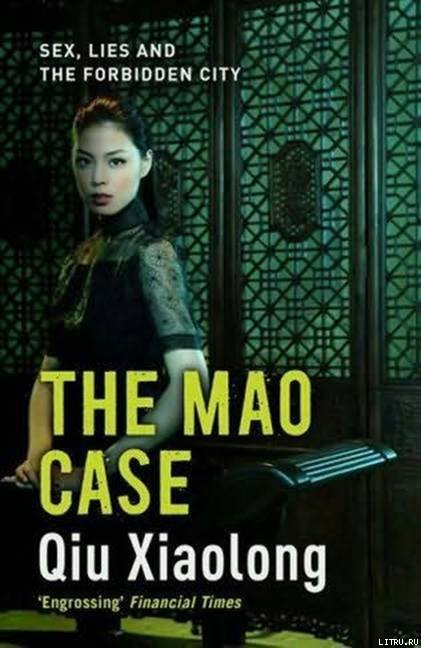

The Mao Case

The sixth book in the Inspector Chen series, 2009

For the people that suffered under Mao

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to many people for their support, particularly to Patricia Mirrlees, whose warm friendship thawed the frozen moments of writing; to Yang Xianyi, whose example of moral integrity inspired the characters in the story; and to Keith Kahla, whose brilliant editorial work helped to present it in its present form.

ONE

CHIEF INSPECTOR CHEN CAO was in no mood to speak at the political studies meeting of the Shanghai Police Bureau’s Party committee.

His mood was due to the topic of the day – the urgency of building spiritual civilization in China. “Spiritual civilization” was a political catchphrase much emphasized in the Party newspapers starting in the mid-nineties. People’s Daily had another editorial on the subject just that morning. In the same issue, however, yet another high-ranking Party official was exposed in a corruption scandal.

So where could the “spiritual civilization” come from? Surely, it wasn’t something that could be pulled out of thin air like a rabbit out of a magician’s hat. Still, Chen had to sit, stiff and serious, at the middle of the conference room table, nodding like a robot, while others talked.

You cannot connect nothing to nothing with broken fingernails…

Whether this bleak image came from a poem he had read long ago, while lying in the sun on some beach, was a detail he couldn’t recall.

In spite of the Party’s propaganda, materialism was sweeping over China. It was a well-known joke that the old political slogan “Look to the future” had become an even more popular maxim, “Look to the money,” for in Chinese, both “future” and “money” are pronounced as qian, exactly the same. But that wasn’t a joke, not exactly. So where would the “spiritual civilization” come from?

“Nowadays, people look at nothing but their own feet,” Party Secretary Li Guohua, the top Party boss in the bureau, spoke, gravely, his heavy eye bags trembling in the afternoon light. “We have to reemphasize the glorious tradition of our Party. We have to rebuild the Communist value system. We have to reeducate people…”

Were people to blame for this? Chen lit a cigarette, rubbing the ridge of his nose with his forefinger and middle finger. After all the political movements under Mao, after the Cultural Revolution, after the eventful summer of 1989, after the numerous corruption cases within the Party system -

“People care for nothing but money,” Inspector Liao, the head of the homicide squad, chipped in loudly. “Let me give you an example. I went to a restaurant last week. An old Hunan restaurant that has been in business for many years, but all of a sudden, it’s a Mao restaurant. There are pictures of Mao, and of his bewitching personal secretaries, posted all over the walls. The menu is full of special dishes that were supposedly favorites of Mao. And so-called Xiang Sister Waitresses, clad in dudou-style bodices with Mao quotations printed on them, strutted around like hookers. The restaurant is shamelessly capitalizing on Mao, who would die from shock if he were resurrected today.”

“And there’s the joke,” Detective Jiang said, “about Mao walking into Tiananmen Square, where a shrewd businessman used him as an instant picture model for tourists, making tons of money. A crying shame -”

“Leave Mao alone,” Party Secretary Li cut in angrily.

A crying shame or not, a joke at the expense of Mao remained a political taboo, Chen observed, pulling over the ashtray. Still, the joke was a vivid illustration of present-day society. Mao had turned into a profitable brand name. Retribution or karma? Chen mused, watching the smoke rings spiral up in the conference room, when he became aware of Li’s fidgeting beside him. He had to say something.

“Economic basis and ideological superstructure.” Chen managed to come out with a couple of Marxist terms he had learned in his college years, but then he checked himself. According to Marx, there is a corresponding relation between the ideological superstructure and the economic basis. What marked the present-day “socialism of Chinese characteristics” was, however, the very incongruity between the two. With the market economy totally capitalistic – and at the “primitive accumulation stage,” to use another Marxist phrase – what kind of a communist superstructure or spiritual civilization could be expected?

Still, he’d better think of something fast. It was expected of him – not only as an “intellectual” having majored in English before being assigned by the state to the police bureau, but also as a chief inspector, and an emerging Party cadre.

“Come on, Chief Inspector Chen, you’re not just a police officer, but a published poet too,” Commissar Zhang urged. A “revolutionary of the older generation,” long retired, Zhang still attended the bureau’s political studies meetings, believing that the current problems were the result of insufficient political study. “Surely you have a lot to tell us about the necessity of rebuilding a spiritual civilization.”

What was behind Zhang’s remark, Chen could easily guess. It wasn’t just an implicit criticism of his being a poet, but also of his being, in Zhang’s eyes, too liberal.

“When I came in to work this morning on a crowded bus,” Chen started over again, clearing his throat, “an old man with a crutch struggled aboard. He fell hard when the bus lurched to a stop. No one got up to give him a seat. A young passenger, seated, commented that it’s no longer the age of Comrade Lei Feng, Mao’s selfless Communist role model -”

He left his sentence unfinished again. Perhaps it was coincidental that Mao kept coming up like a returning ghost. Chen ground out his cigarette, ready to finish his sentence when his cell phone rang shrilly. Without looking at the others in room, he answered it.

“Hi, this is Yong,” a woman’s voice said, clear and crisp, “I’m calling about Ling.”

Ling was Chen’s girlfriend in Beijing, or to be exact, ex-girlfriend, though they hadn’t exactly said so explicitly. Yong, a friend and former colleague of Ling’s, had tried to help during their prolonged off-and-on relationship, which went back as early as his college years.

“Oh? What’s happened to Ling?” he exclaimed, drawing surprised stares from his colleagues. He stood up in a hurry, saying to the room, “Sorry, I have to take this.”

“Ling got married,” Yong said.

“What?” he said, striding out into the corridor.

He really shouldn’t have been astonished. Their relationship had long been on the rocks, what with the insurmountable problem of her being an HCC – a high cadre’s child, her father was a top-ranking Party cadre, with his being unable to imagine himself becoming an HCC, because of her, even for her sake. The friction was intensified by his dislike of the social injustice, with the distance between Beijing and Shanghai, and by so many things between them…

Ling was not to blame, he had kept telling himself. Still, the news came as a shattering blow.

“He’s another HCC, but also a successful businessman and a Party official. She doesn’t really care for all that, you know…”

He listened, leaning into a corner, gazing at the opposite wall, which resembled a piece of blank paper. Somehow he felt like an audience, listening to a story about something that had happened to others.