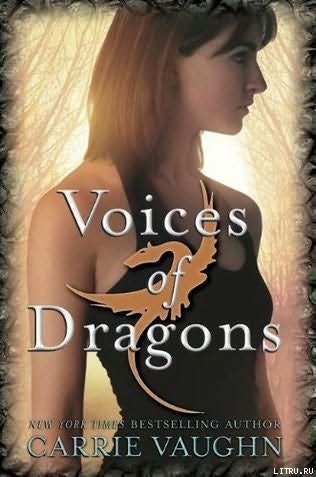

Carrie Vaughn

Voices of Dragons

To Mom, Dad, and Rob

1

Her parents were going to kill her for this.

Kay Wyatt adjusted her grip, wedging her fist more firmly into the crevice. A scab on her knuckle broke and started bleeding. The pain of it wasn’t worse than any of the other minor injuries she was subjecting herself to, clinging to the side of a pile of weathered boulders, slowly creeping up with only her hands and feet to support her. Free-climbing in a remote area alone? Yeah, her parents were going to kill her.

As if that wasn’t dangerous enough already, she had to do it right on the border with Dragon. Not that she looked at it that way. She figured no one would notice; this really was the middle of nowhere. No Jeep trails, no hikers or campers—no one came here. It seemed like a good place to go when she didn’t want to be found. She really didn’t want to be found at the moment. She had to think of what to tell Jon about homecoming. He’d asked her out, and she should have been thrilled. Anyone else would have been. But she had to think about it.

The dragons only ever came close enough to the border to appear as specks, soaring in the distance, deep in their own territory. She’d be safe.

She’d found this place by studying topographic maps and wondering about the steep hills that lined the river. She’d climbed all the sanctioned rock faces, rafted the local rivers, hiked the trails. She’d grown up out here. But she wanted to see someplace new. She wanted to get out on her own. She wanted to do something.

Over the summer, she and Jon had gone kayaking on the Silver River south of town after dark. Being on the river under a full moon had been amazing, but her parents had caught her driving home with a wet kayak at midnight and chewed her out about how dangerous it was, how she could have gotten hurt, and whatever. Then there was the time she free-climbed the wall at the rec center, just to see if she could. She’d have gotten away with that one if the manager hadn’t found her.

She’d stashed her gear in the Jeep the night before so her parents wouldn’t ask questions, left the house after breakfast, and didn’t tell them where she was going. Planned rebellion. It didn’t matter that the first rule of any outdoor activity was tell someone where you were going. She’d decided she just didn’t want to. And if something happened? If she managed to fall and break herself? She could imagine the brouhaha when she turned up missing—then when they figured out exactly where she’d gone. Searching the area would cause an international incident. She might actually start a war if she fell and needed to be rescued. Which was all the more incentive not to fall.

But nothing was going to happen. She’d climbed more difficult rocks than this. Free-climbed, even. She wasn’t doing anything she hadn’t done a thousand times before. Only the context had changed.

And nothing was going to happen to her because nothing ever had happened to her except getting grounded. Like she’d told her parents after the kayaking-at-night incident, at least she wasn’t doing drugs. Her father, the county sheriff, hadn’t been amused.

The irony of the whole thing was that both her parents were supposed to protect the border. Her dad was a cop, her mother the assistant director at the Federal Bureau of Border Enforcement. They didn’t guard against the dragons—the military would be called in for that. Instead, they were supposed to keep people out, be on the lookout for curiosity seekers and die-hard romantics who wanted to see dragons and thought they could sneak over the border, and the warmongers who wanted to get close enough to go hunting for dragons. The government took protecting the border very seriously.

So, if they knew about this, her parents would kill her for more reasons than she could count.

Balancing on her toes, Kay found a grip for her left hand. Joints straining, she edged another few inches up the rock. Then a few more. Her hands were dry with chalk, cracked and bloody. Her lips were chapped. Her whole body was sweaty. The sun was baking down on an unseasonably warm day. But really, this was bliss. Just her body and the rock, with nothing but the sound of a few birds and the nearby creek tumbling down the hillside.

A few more inches, stretching spread-eagle on the rock in her quest for the next purchase. Then a few more, legs straight, hanging by her fingertips. Looking up, the rock was a solid granite wall stretching before her forever. One inch at a time, that was how her father had taught her. You can’t do anything but worry about the few inches right in front of you. So she did, breathing steadily, making progress until, almost suddenly, there was no more rock, and she was at the top, looking down the hillside from her vantage. She’d done it, and she hadn’t broken herself.

After resting and taking a long drink of water, Kay changed from her climbing shoes into her hiking boots and went back down the rock face the easy way, off the back side where it joined the forested mountainside, sliding down the dirt and old pine needles, bouncing from one tree to the next. It had taken her an hour to climb up and only ten minutes to fly down, to where the boulder field continued on to mark the edge of the creek. She’d follow it to where it branched south and then, before anyone noticed, cut across to the trailhead where she’d parked her Jeep.

She stopped by Border River, a couple yards wide and a few feet deep, to soak her hands in the icy water. She had new blisters and calluses to add to her collection, and the rushing water numbed the aches. For a long moment, she balanced on the rocks, letting her hands get cold, enjoying the calm.

She’d been so careful the rest of the time, she never expected her foot to slip out from under her when she moved to stand up. The rock must have had a wet spot, or she hit a crumbly piece of boulder—gravel instead of stone, it slid instead of holding her foot. Yelping, she toppled over and rolled into the creek.

The chill water shocked her sweaty, overheated body, and at first she could only freeze, numb and sputtering, hoping to keep her head above water. The current carried her. These mountain creeks were always deeper and faster moving than they looked, and she tumbled, dragged by the water, buffeted by rocks. When she finally started flailing, struggling to find something, anything, she could grab to stop her progress, she found nothing. Her hands kept slipping off mossy rocks or splashing against the current. She’d always discounted the idea of someone drowning after getting swept away in one of these creeks, when they could just put their feet down and stand up. But she couldn’t seem to get her feet under her. The current kept snatching her, turning her, dunking her. She was already exhausted from her climb, and now this.

When something grabbed at her, she clung to it. A log, some kind of debris fallen into the creek. That was what she thought. But her hands didn’t close on sodden bark or vegetation. The thing she’d washed up against was slick, almost like plastic, but warm and yielding. And it moved. It closed around her and pulled. Water filled her eyes; she couldn’t see. The world seemed to flip.

Then she washed up on dry land. She lay on solid, gritty earth and smelled dirt. She spent a long moment coughing her lungs out, heaving up water until she couldn’t cough anymore. Hunched over, learning how to breathe again, she got her first look around and realized she’d ended up on the north side of the creek. The wrong side of the border.

A deep, short growl echoed above her. She rolled over and looked up. She was in shadow, and a dragon hunched over her. A real dragon, close up. Two stories tall, a long, finely wrought head on a snaking neck, and a lithe, scale-covered body. It was gray like storm clouds, shimmering to ice blue or silver depending on how the sunlight hit it. Its eyes were black, depthless black. Bony ridges made its gaze look quizzical, curious.