Tatjana Soli

The Lotus Eaters

© 2010

For my mom,

who taught me about

brave girls crossing oceans

For Gaylord,

with love and gratitude

… we reached the country of the Lotus-eaters, a race that eat the flowery lotus fruit… Now these natives had no intention of killing my comrades; what they did was to give them some lotus to taste. Those who ate the honeyed fruit of the plant lost any wish to come back and bring us news. All they now wanted was to stay where they were with the Lotus-eaters, to browse on the lotus, and to forget all thoughts of return.

– HOMER, The Odyssey

ONE. The Fall

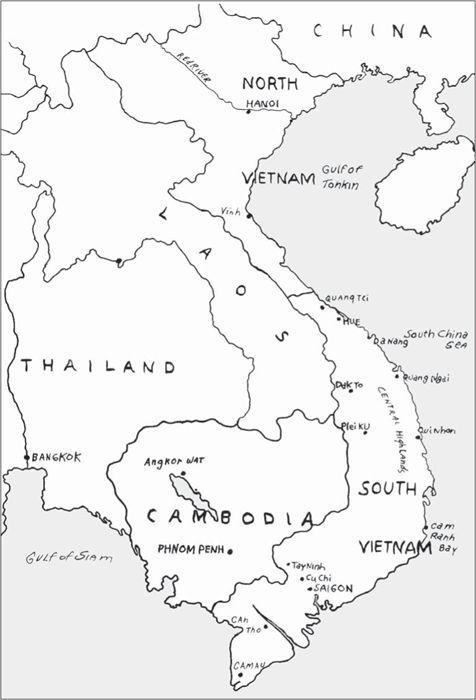

April 28, 1975

The city teetered in a dream state. Helen walked down the deserted street. The quiet was eerie. Time running out. A long-handled barber’s razor, cradled in the nest of its strop, lay on the ground, the blade’s metal grabbing the sun. Unable to resist, she leaned down to pick it up, afraid someone would split his foot open running across it. A crashing noise down the street distracted her-dogs overturning garbage cans-and she snatched blindly at the razor. Drawing her hand back, she saw a bright pinprick of blood swelling on her finger. She cursed at her stupidity and kicked the razor, strop and all, to the side of the road and hurried on.

The unnatural silence allowed Helen to hear the wailing of the girl. The child’s howl was high and breathless, defiant, rising, alone and forlorn against the buildings, threading its way through the air, a long, plaintive note spreading its complaint. Helen crossed the alley and went around a corner to see a small child of three or four, hard to tell with the unrelenting malnourishment, standing against the padlocked doorway of a bar. Her face and hair were drenched with the effort of her crying. She wore a dirty yellow cotton shirt sizes too large, bottom bare, no shoes. Dirt circled between her toes.

The pitiful scene begged a photo. Helen hesitated, hoping an adult would come out of a doorway to rescue the child. She had only days or hours left in-country. Breathless, the girl staggered a few steps forward to the curb, eyes flooded in tears, when a man on a bicycle flew around the corner, pedaling at a furious speed, clipping the curb and almost running her down. Helen lurched forward without thinking, grabbed the girl’s arm and pulled her back, speaking quickly in fluent Vietnamese: “Little girl, where is Mama?”

The child hardly looked at her, the small body wracked with sobs. Helen’s throat constricted. A mistake, stopping. A pact made to herself that at this late date she wouldn’t get involved. The street rolled away in each direction, empty. No woman approached them.

Tired, Helen knelt down so she was at eye level to the child. In a headlong lunge, the girl wrapped both arms around Helen’s neck. Her cries quieted to soft cooing.

“What’s your name, honey?”

No answer.

“Should I take you home? Home? To Mama? Where do you live?”

Rested, the girl began to sob again with more energy, fresh tears.

No good deed goes unpunished. The camera bag pulled, heavy and bulky. As she held the girl, walking up and down the street to flag attention, it knocked against her hip. She slipped the shoulder strap off and set it down on the ground, all the while talking under her breath to herself: “What are you doing? What are you doing? What are you doing?” The child was surprisingly heavy, although Helen could feel ribs and the sharp, pinionlike bones of shoulder blades. The legs that wrapped viselike around Helen’s waist were sticky, a strong scent of urine filling her nostrils.

A stab of impatience. “I’ve got to go, sweetie. Where is Mama?”

She bounced the girl to quiet her and paced back and forth. Her mind wasn’t clear; why was she losing her precious hours, involving herself now, when she had passed hundreds of desperate children before? But she had heard this one’s cries so clearly. A sign? A sign she was losing it was more like it, Linh would say.

A young woman hurried across the intersection, glanced at Helen and the child, then looked away.

The orphanage was overflowing. Should she take the girl home with her? Once they abandoned this corner, she would be Helen’s responsibility. Could she take her out of the country with Linh? What had she been thinking to stop? Was it a trap? By whom? Was it a test? By what?

Helen stroked the girl’s hair, irritated. She had a heart-shaped face, ears like perfect small shells. A bath and a nice dress would make her quite lovely.

Ten, fifteen minutes passed. The idea of this being a sign seemed more stupid by the minute. Not a soul came, nothing except the tinny, popping sound of guns far away. Helen toyed with the idea of putting the girl back down. Surely the family was close by, was searching for her. No harm done in keeping the girl company for a few minutes. Not her responsibility, after all. When she began to kneel to deposit her back on the ground, the girl’s arms tightened to a choke hold around her neck, and Helen, resigned, strained back up. All wrong; a terrible mistake. A proof that she was failing. Linh would be worrying by now, might even try to go out to find her.

Helen bent and fished for the strap of her camera bag, putting it on the other shoulder to balance the weight. Maybe it was a sign. Insane, but what else could she do but take the child with her?

Halfway down the street, a woman’s voice yelled from behind them. Helen turned to see a plain, moonfaced woman with thin, cracked lips stride toward them.

“Are you her mother?” Helen asked, guilt welling up. “I wasn’t trying to take her-”

The woman yanked the girl out of Helen’s arms, eyes pinched hard. The girl whimpered as the mother swatted her on the leg and scolded her.

“She couldn’t tell me where she lived,” Helen said.

But the mother had already turned without another glance and stalked away. The girl looked over the mother’s shoulder, dark eyes expressionless. In a few more steps, they disappeared around the corner.

For the briefest moment Helen felt wronged, missed the weight on her hip and the sticky legs, but then the feeling was gone. How had the mother been so neglectful anyway? It rankled that she had not been thanked or even acknowledged for her effort. But with the shedding of that temporary burden, the old excitement buoyed up in her again. The possibility of the girl disappeared into the past. She’d better pull herself together. She picked up her bag, checked her watch, and ran.

On a normal day the activity in the streets so filled her eye that she hardly knew where to turn, torn whether to focus her camera on the intricate tableaus of open-air barbers on the sidewalk cutting their customers’ hair, or tea vendors sweating over their fires and flame-blackened pots, or ink-haired boys selling everything from noodles to live chickens to cigarettes, or old men with whisk beards as peaceful as Buddhas playing their endless games of co tuong. And, too, there was the endless flotsam and jetsam of the war: beggars and amputees thronging everyplace where foreigners were likely to drop money.

But today streets were vacant, the broken windows and smashed doors like gouged-out features of a face once familiar. The people gone, or rather hidden, the streets deformed by their absence.

Helen’s Saigon had always been about selling-chickens, information, or lovely young women, it didn’t matter. It had once been called the Pearl of the Orient, but by people who had not been there in a very long time. Saigon had never been Paris, but now it was a garrison town, unlovely, a stinking refugee shantyville filled with the angry, the betrayed, the dispossessed, but she had made it her home, and she couldn’t bear that soon she would have to leave.