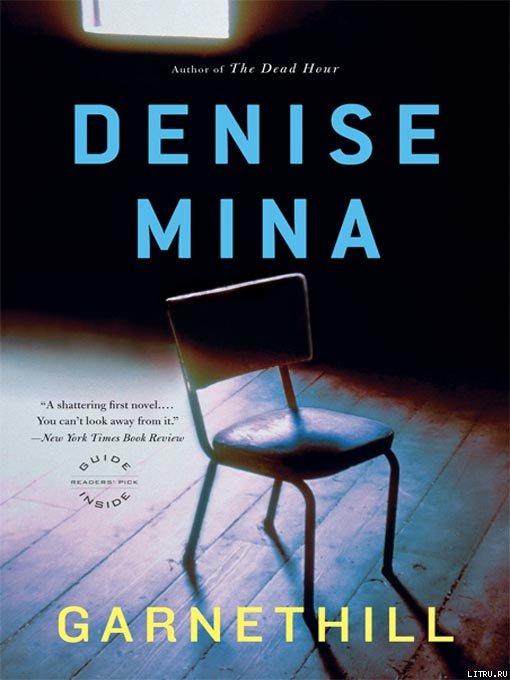

Denise Mina

Garnethill

The First Book in the Garnethill Trilogy, 1998

To my mum, Edith

Chapter 1

Maureen dried her eyes impatiently, lit a cigarette, walked over to the bedroom window, and threw open the heavy red curtains. Her flat was at the top of Garnethill, the highest hill in Glasgow, and the craggy North Side lay before her, polka-dotted with cloud shadows. In the street below, art students were winding their way up to their morning classes.

When she first met Douglas she knew that this would be a big one. His voice was soft and when he spoke her name she felt that God was calling or something. She fell in love despite Elsbeth, despite his lies, despite her friends' disapproval. She remembered a time when she would watch him sleep, his eyes fluttering behind the lids, and she found the sight so beautiful that it winded her. But on Monday night she woke up and looked at him and knew it was over. Eight long months of emotional turmoil had passed as suddenly as a fart.

At work she told Liz.

"Oh, I know, I know," said Liz, back-combing her blond hair with her fingers. "Before I met Garry I used to go dancing…"

Liz was crap to talk to. It didn't matter what the subject was, she always brought it back round to her and Garry. Garry was a sex god, everyone fancied him, said Liz, she had been lucky to get him. Maureen was sure that Garry was the source of this information. He came by the ticket booth sometimes, hanging in the window, flirting at Maureen when Liz wasn't looking.

Liz began a rambling story about liking Garry and then not liking him and then liking him again. Two sentences into it Maureen realized she had heard the story before. Her head began to ache. "Liz," she said, "would you do me a favor and get the phones today? He's supposed to phone and I don't want to talk to him."

"Sure," said Liz. "No bother."

At half-ten Liz opened her eyes wide. "Sorry," she said theatrically into the phone, "she's not here. No, she won't be in then either. Try tomorrow." She hung up abruptly and looked at Maureen. "Pips went."

"Pips? Was he calling from a phone box?"

"Aye."

Maureen looked at her watch. "That's strange," she said. "He should be at work."

Half an hour later Liz answered the phone again. "No," she said flatly, "I told you she's not in. Try tomorrow." She put the phone down. "Well," she said, clearly impressed, "he's eager."

"Was he calling from a phone box again?"

"Sounded like it. I could hear people talking in the background like before."

The ticket booth was at the front of the Apollo Theatre, set into a triangular dip in the neoclassical facade so that customers didn't have to stand in the rain while they bought their tickets. It was a dull gray day outside the window, the first bitter day of autumn, coming just as warm afternoons had begun to feel like a birthright. The cold wind brushed under the window, eddying in the change tray. The second post brought a letter stamped with an Edinburgh postmark and addressed to Maureen. She folded it in half and slipped it into her pocket, pulled the blind down at her window and told Liz she was going to the loo.

Douglas said he was living with Elsbeth but Maureen felt sure they were married: twelve years together seemed like a lifetime and he lied about everything else. Three months ago the elections for the European Parliament had been held and Douglas's mother was returned for a second term as the MEP for Strathclyde. All the local newspapers carried variations of the same carefully staged photo opportunity. Carol Brady was standing on the forecourt of a big Glasgow hotel, smiling and holding a bunch of roses. Douglas was standing in the background next to the provost, his arm slung casually around a pretty blond woman's waist. The caption named her as Elsbeth Brady, his wife.

Maureen had written to the General Register in Edinburgh, sending a postal order and Douglas's details, asking for a fifteen-year search on the public marriage register. She remembered caring desperately when she sent the letter three months ago but now the response had arrived it was just a curiosity.

The outer door was jammed open by Audrey's mop bucket. One of the cubicle doors was shut and a thin string of smoke rose from behind the door. Maureen tiptoed over the freshly mopped floor, locked the cubicle door and sat on the edge of the toilet, ripping the fold open with her finger.

The marriage certificate said that he had been married in 1987 to Elsbeth Mary McGregor. Maureen felt a burst of lethargy like an acid rush in her stomach.

"Hello?" called Audrey from the other cubicle, speaking in the strangled accent she reserved for addressing the management.

"It's all right," said Maureen. "It's only me. Smoke on."

When she got back to the office Liz was excited. "He phoned again," she said, looking at Maureen as if this were great news. "I said you weren't in today and he shouldn't phone back. He must be mad for you."

Maureen couldn't be arsed responding. "I really don't think so," she said, and slipped his marriage certificate into her handbag.

At six o'clock Maureen phoned Leslie at work. "Listen, d'ye fancy meeting an hour earlier?"

"I thought your appointment with the psychiatrist was on Wednesdays."

"Auch, aye," said Maureen, cringing. "I'll just dog it today."

"Right, doll," said Leslie. "I'll get you there at, what, half-six?"

"Half-six it is," said Maureen.

Liz helped to shut up the booth and then left Maureen to carry the day's takings around the corner to the night safe. Maureen walked slowly, taking the long way through the town, avoiding the Albert Hospital. Cathedral Street is a wind tunnel. It's a long slip road for the M8 motorway and was built as a dual carriageway to accommodate the heavy traffic. The tall office buildings on either side prevent cross breezes from tempering the eastern wind as it rolls down the hill, gathering nippy momentum as it crosses the graveyard and sweeps down the broad street. Maureen had misjudged the weather, her thin cotton dress and woolen jacket did nothing to keep out the cold and her toes were numb in her boots.

Louisa would be sitting behind her desk on the ninth floor of the Albert right now, her hands clenched in front of her, watching the door, waiting for her. Maureen didn't want to go. The echoey corridors and smell of industrial disinfectant freaked her every time, reminding her of her stay in the Northern. The nurses there were kind but they fed her with food she didn't like and dressed her with the curtains open. The toilets didn't have locks on them so that the patients couldn't misuse the privilege of privacy for a suicide bid. When she first got out, each day was a trial: she was terrified that she might snap and again be a piece of meat to be dressed every morning in case of visitors. Her current therapist, Dr. Louisa Wishart, said that her terror was a fear of vulnerability, not loss of dignity. And every time she went to see Louisa the same fifty-year-old underweight man was sitting in the waiting room. He kept trying to catch her eye and talk to her. She cut her waiting time as thin as possible to avoid him, sitting in one of the toilets or hovering around in the lobby.

She had been attending the Albert since Angus Farrell at the Rainbow Clinic referred her eight months before. By the time she had her first session with Louisa she knew she was going to be all right, that therapy was an empty gesture to medicalize a deep sadness. She tried to stop going to Louisa but her mother, Winnie, caused an almighty fuss, phoning her four times a day to ask how she was. She went back to the Albert and said she had been resisting a breakthrough in her therapy.