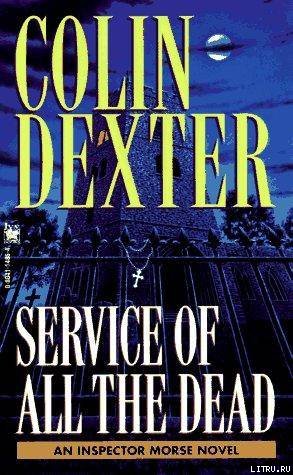

Colin Dexter

Service of all the dead

The fourth book in the Inspector Morse series, 1979

For John Poole

I had rather be a doorkeeper in the house

of my God: than to dwell in the tents

of ungodliness

(Psalm 84, v.10)

THE FIRST BOOK OF CHRONICLES

Chapter One

Limply the Reverend Lionel Lawson shook the last smoothly gloved hand, the slim hand of Mrs Emily Walsh-Atkins, and he knew that the pews in the old church behind him were now empty. It was always the same: whilst the other well-laundered ladies were turning their heads to chat of fetes and summer hats, whilst the organist played his exit voluntary, and whilst the now discassocked choirboys tucked their T-shirts into flare-line jeans, Mrs Walsh-Atkins invariably spent a few further minutes on her knees in what had sometimes seemed to Lawson a slightly exaggerated obeisance to the Almighty. Yet, as Lawson knew full well, she had plenty to be thankful for. She was eighty-one years old, but managed still to retain an enviable agility in both mind and body, only her eyesight was at last beginning to fail. She lived in north Oxford, in a home for elderly gentlewomen, screened off from the public gaze by a high fence and a belt of fir-trees. Here, from the front window of her living-room, redolent of faded lavender and silver-polish, she could look out on to the well-tended paths and lawns where each morning the resident caretaker unobtrusively collected up the Coca Cola tins, the odd milk-bottle and the crisp-packets thrown over by those strange, unfathomably depraved young people who, in Mrs Walsh-Atkins' view, had little right to walk the streets at all – let alone the streets of her own beloved north Oxford. The home was wildly expensive; but Mrs W.-A. was a wealthy woman, and each Sunday morning her neatly sealed brown envelope, lightly laid on the collection-plate, contained a folded five-pound note.

‘Thank you for the message, Vicar.'

'God bless you!'

This brief dialogue, which had never varied by a single word in the ten years since Lawson had been appointed to the parish of St Frideswide's, was the ultimate stage in non-communication between a priest and his parishioner. In the early days of his ministry, Lawson had felt vaguely uneasy about 'the message' since he was conscious that no passage from his sermons had ever been declaimed with particularly evangelistic fervour; and in any case the role of some divinely appointed telegram-boy was quite inappropriate – indeed, quite distasteful – to a man of Lawson's moderately high-church leanings. Yet Mrs Walsh-Atkins appeared to hear the humming of the heavenly wires whatever his text might be; and each Sunday morning she reiterated her gratitude to the unsuspecting harbinger of goodly tidings. It was purely by chance that after his very first service Lawson had hit upon those three simple monosyllables – magical words which, again this Sunday morning, Mrs Walsh-Atkins happily clutched to her bosom, along with her Book of Common Prayer, as she walked off with her usual sprightly gait towards St Giles', where her regular taxi-driver would be waiting in the shallow lay-by beside the Martyrs' Memorial.

The vicar of St Frideswide's looked up and down the hot street. There was nothing to detain him longer, but he appeared curiously reluctant to re-enter the shady church. A dozen or so Japanese tourists made their way along the pavement opposite, their small, bespectacled cicerone reciting in a whining, staccato voice the city's ancient charms, his sing-song syllables still audible as the little group sauntered up the street past the cinema, where the management proudly presented to its patrons the opportunity of witnessing the intimacies of Continental-style wife-swapping. But for Lawson there were no stirrings of sensuality: his mind was on other things. Carefully he lifted from his shoulders the white silk-lined hood (M.A. Cantab.) and turned his gaze towards Carfax, where already the lounge-bar door of The Ox stood open. But public houses had never held much appeal for him. He sipped, it is true, the occasional glass of sweet sherry at some of the diocesan functions; but if Lawson's soul should have anything to answer for when the archangel bugled the final trumpet it would certainly not be the charge of drunkenness. Without disturbing his carefully parted hair, he drew the long white surplice over his head and turned slowly into the church.

Apart from the organist, Mr Paul Morris, who had now reached the last few bars of what Lawson recognised as some Mozart, Mrs Brenda Josephs was the only person left in the main body of the building. Dressed in a sleeveless, green summer frock, she sat at the back of the church, a soberly attractive woman in her mid- or late thirties, one bare browned arm resting along the back of the pew, her finger-tips caressing its smooth surface. She smiled dutifully as Lawson walked past; and Lawson, in his turn, inclined his sleek head in a casual benediction. Formal greetings had been exchanged before the service, and neither party now seemed anxious to resume that earlier perfunctory conversation. On his way to the vestry Lawson stopped briefly in order to hook a loose hassock into place at the foot of a pew, and as he did so he heard the door at the side of the organ bang shut. A little too noisily, perhaps? A little too hurriedly?

The curtains parted as he reached the vestry and a gingery-headed, freckle-faced youth almost launched himself into Lawson's arms.

'Steady, boy. Steady! What's all the rush?'

'Sorry, sir. I just forgot… ' His breathless voice trailed off, his right hand, clutching a half-consumed tube of fruit gums, drawn furtively behind his back.

'I hope you weren't eating those during the sermon?'

'No, sir.'

'Not that I ought to blame you if you were. I can get a bit boring sometimes, don't you think?' The pedagogic tone of Lawson's earlier words had softened now, and he laid his hand on the boy's head and ruffled his hair lightly.

Peter Morris, the organist's only son, looked up at Lawson with a quietly cautious grin. Any subtlety of tone was completely lost upon him; yet he realised that everything was all right, and he darted away along the back of the pews.

'Peter!' The boy stopped in his tracks and looked round. 'How many times must I tell you? You're not to run in church!'

'Yes, sir. Er – I mean, no, sir.'

'And don't forget the choir outing next Saturday.'

' 'Course not, sir.'

Lawson had not failed to notice Peter's father and Brenda Josephs talking together in animated whispers in the north porch; but Paul Morris had now slipped quietly out of the door after his son, and Brenda, it seemed, had turned her solemn attention to the font: dating from 1345, it was, according to the laconic guidebook, number one of the 'Things to Note'. Lawson turned on his heel and entered the vestry.

Harry Josephs, the vicar's warden, had almost finished now. After each service he entered, against the appropriate date, two sets of figures in the church register: first, the number of persons in the congregation, rounded up or down to the nearest five; second, the sum taken in the offertory, meticulously calculated to the last half-penny. By most reckonings, the Church of St Frideswide's was a fairly thriving establishment. Its clientele was chiefly drawn from the more affluent sectors of the community, and even during the University vacations the church was often half-full. It was to be expected, therefore, that the monies to be totalled by the vicar's warden, then checked by the vicar himself, and thereafter transferred to the church's number-one account with Barclays Bank in the High, were not inconsiderable. This morning's takings, sorted by denominations, lay on Lawson's desk in the vestry: one five-pound note; about fifteen one-pound notes; a score or so of fifty-pence pieces and further sundry piles of smaller coinage, neatly stacked in readily identifiable amounts.