A DYING LIGHT IN CORDUBA

In Memory of Edith Pargeter

Romans, in or out of Rome

M. Didius Falco a frantic expectant father; a hero

Helena Justina a thoroughly reasonable expectant mother; a heroine

D. Camillus Verus her father, also quite reasonable, for a senator

Julia Justa her mother, as reasonable as you could expect

A. Camillus Aelianus bad-tempered, self-righteous, and up to no good

Q. Camillus Justinus too sweet-natured and good to appear

Falco's Ma who may be spooning broth into the wrong mouth

Claudius Laeta top clerk, and aiming higher

Anacrites Chief Spy, and as low as you can get

Momus an "overseer"; the man who spies on spies

Calisthenus an architect who stepped on something nasty

Quinctius Attractus a senator with big Baetican aspirations

T. Quinctius Quadratus his son, a high-flyer grounded in Baetica

L. Petronius Longus a loyal and useful friend

Helva a short-sighted usher who can look the other way

Valentinus a skillful gate-crasher; on his way out

Perella a mature dancer with unexpected talents

Stertius a transport manager with inventive ideas

The Baetican Proconsul who doesn't want to be involved

Cornelius ex-quaestor of Baetica; leaving the scene hastily

Gn. Drusillus Placidus a procurator with a crazy fixation on probity

Nux a dog about town

Baeticans, out of and in Baetica

Licinius Rufius old enough to know there's never enough profit?

Claudia Adorata his wife, who hasn't noticed anything

Rufius Constans his grandson, a young hopeful with a secret

Claudia Rufina a serious girl with appealing prospects

Annaeus Maximus a community leader; leading to the bad?

His Three Sons known as Spunky, Dotty and Ferret; say no more!

Aelia Annaea a widow with a very attractive asset

Cyzacus senior a bargee who has barged into something dubious?

Cyzacus junior an unsuccessful poet; paddling the wrong raft?

Gorax a retired gladiator; no chicken!

Norbanus a negotiator who has fixed a dodgy contract?

Selia an extremely slippery dancer

Two musicians who are not employed for their musical skills

Marius Optatus a tenant with a grievance

Marmarides a driver whose curios are much in demand

Cornix a bad memory

The Quaestor's clerk who runs the office

The Proconsul's clerks who drink a lot (and run the office)

Prancer a very old country horse

PART ONE:

ROME

A.D. 73: beginning the night of 31 March

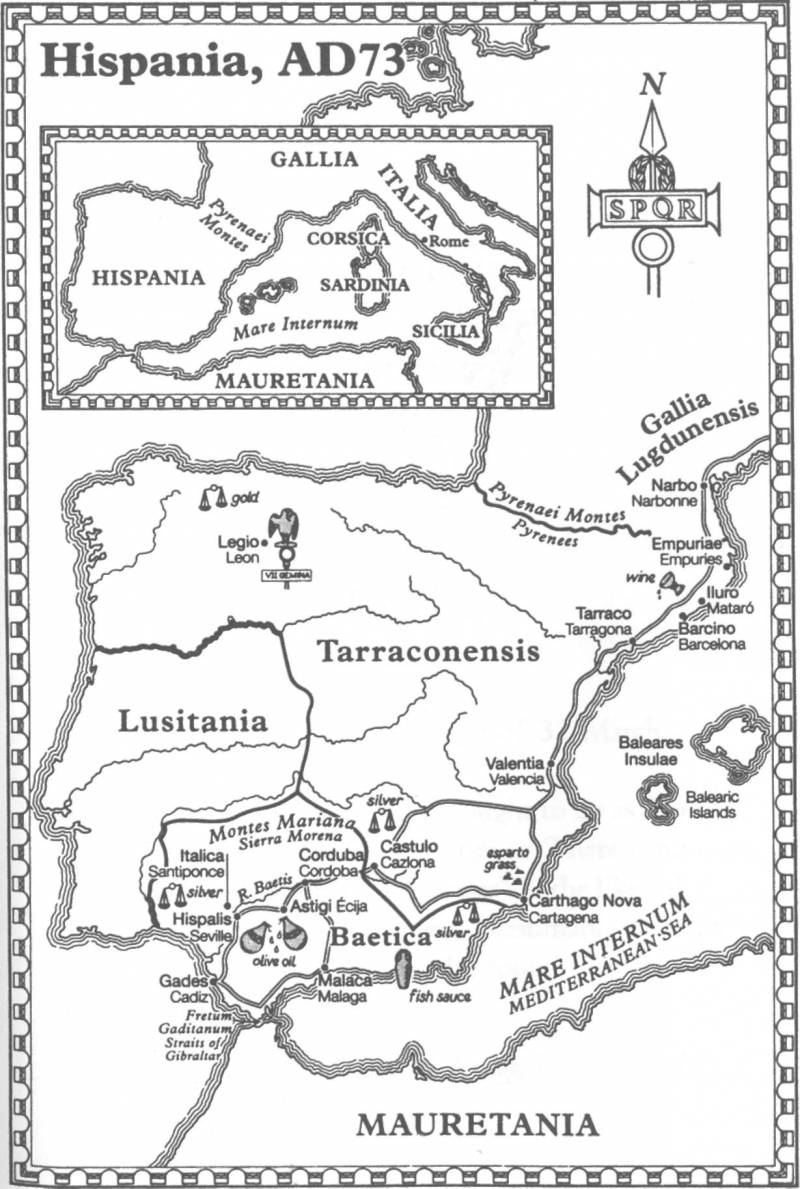

Cordobans of any status surely sought to be as Roman as the Romans themselves, or more so. There is no evidence of a "national consciousness" in the likes of the elder Seneca, although there was presumably a certain sympathy among native sons who found themselves in Rome together... Robert C. Knapp, Roman Cordoba

ONE

Nobody was poisoned at the dinner for the Society of Olive Oil Producers of Baetica—though in retrospect, that was quite a surprise.

Had I realized Anacrites the Chief Spy would be present, I would myself have taken a small vial of toad's blood concealed in my napkin and ready for use. Of course he must have made so many enemies, he probably swallowed antidotes daily in case some poor soul he had tried to get killed found a chance to slip essence of aconite into his wine. Me first, if possible. Rome owed me that.

The wine may not have been as smoothly resonant as Falernian, but it was the Guild of Hispania Wine Importers' finest and was too good to defile with deadly drops unless you held a very serious grudge indeed. Plenty of people present seethed with murderous intentions, but I was the new boy so I had yet to identify them or discover their pet gripes. Maybe I should have been suspicious, though. Half the diners worked in government and the rest were in commerce. Unpleasant odors were everywhere.

I braced myself for the evening. The first shock, an entirely welcome one, was that the greeting-slave had handed me a cup of fine Barcino red. Tonight was for Baetica: the rich hot treasure-house of southern Spain. I find its wines oddly disappointing: white and thin. But apparently the Baeticans were decent chaps; the minute they left home they drank Tarraconensian—the famous Laeitana from northwest of Barcino, up against the Pyrenees where long summers bake the vines but the winters bring a plentiful rainfall.

I had never been to Barcino. I had no idea what Barcino was storing up for me. Nor was I trying to find out. Who needs fortunetellers' warnings? Life held enough worries.

I supped the mellow wine gratefully. I was here as the guest of a ministerial bureaucrat called Claudius Laeta. I had followed him in, and was lurking politely in his train while trying to decide what I thought of him. He could be any age between forty and sixty. He had all his hair (dry-looking brown stuff cut in a short, straight, unexciting style). His body was trim; his eyes were sharp; his manner was alert. He wore an ample tunic with narrow gold braid, beneath a plain white toga to meet Palace formality. On one hand he wore the wide gold ring of the middle class; it showed some emperor had thought well of him. Better than anyone yet had thought of me.

I had met him while I was involved in an official inquiry for Vespasian, our tough new Emperor. Laeta had struck me as the kind of ultra-smooth secretary who had mastered all the arts of looking good while letting handymen like me do his dirty work. Now he had taken me up—not due to any self-seeking of mine though I did see him as a possible ally against others at the Palace who opposed promoting me. I wouldn't trust him to hold my horse while I leaned down to tie my boot thong, but that went for any clerk. He wanted something; I was waiting for him to tell me what.

Laeta was top of the heap: an imperial ex-slave, born and trained in the Palace of the Caesars amongst the cultivated, educated, unscrupulous orientals who had long administered Rome's Empire. Nowadays they formed a discreet cadre, well behind the scenes, but I did not suppose their methods had changed from when they were more visible. Laeta himself must have somehow survived Nero, keeping his head down far enough to avoid being seen as Nero's man after Vespasian assumed power. Now his title was Chief Secretary, but I could tell he was planning to be more than the fellow who handed the Emperor scrolls. He was ambitious, and looking for a sphere of influence where he could really enjoy himself. Whether he took backhanders in the grand manner I had yet to find out. He seemed a man who enjoyed his post, and its possibilities, too much to bother. An organizer. A long-term planner. The Empire lay bankrupt and in tatters, but under Vespasian there was a new mood of reconstruction. Palace servants were coming into their own.