Blake Charlton

Spellwright

© 2010

To the memory of my grandmother,

Jane Bryden Buck (1912-2002),

for long stories and lessons in kindness

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing a novel is like escaping a cocoon you spun when you were someone less wise.

That being so, a complete list of my gratitude would include everyone who helped me come to terms with my disability. However, listing all the teachers, students, and friends who supported me would make Spellwright heavy enough to qualify as exercise equipment. So if you’ve opened this book because of the name on its spine-rather than its title-know that you are appreciated and loved.

My particular gratitude I dedicate to those who sacrificed for and believed in Spellwright: to James Frenkel, for limitless wisdom and gallons of industrial-strength editorial elbow grease; to Matt Bialer, for taking a chance on a young writer and helping him grow; to Todd Lockwood and Irene Gallo, for the stunning cover; to Tom Doherty and everyone at Tor, for their support; to Stanford Medical School and the Medical Scholars Research Program, for making my dual career possible; to Tad Williams, my glabrous, fantasy-writing, YMCA-basketball Jedi Master, whose fingerprints are all over this story; to Daniel Abraham, for lunar physics explanations and inspiring the concept of “quaternary thoughts” with a casual and brilliant comment over lunch; to Terra Chalberg, friend and publication guardian angel during a trying time; to Nina Nuangchamnong and Jessica Weare, foul-weather-friends and manuscript polishers extraordinaire; to Dean Laura King-wherever she might be-for pulling me out of the rabid premed wolf pack and teaching me to write and chase dreams; to Joshua Spanogle, for friendship and advice on the med student-novelist life; to Swaroop Samant and Erin Cashier, for fiery criticism and golden praise; to Asya Agulnik, Deanna Hoak, Kevan Moffett, Julia Manzerova, Mark Dannenberg, Nicole C. Hastings, Tom DuBois, Amy Yu, Ming Cheah, and Christine Chang, for fresh perspectives and wisdom; to Kate Sargent, for slogging though clunky early drafts; to The Wordspinners (Madeleine Robins, Kevin Andrew Murphy, Jaqueline Schumann, Jeff Weitzel, and Elizabeth Gilligan), for fellowship and teaching me how to talk shop; to Andrea Panchok-Berry, for reading the first, very misspelled draft; to Vicky Greenbaum, for early encouragement and inspiration; and, with all of my love, to Genevieve Johansen, Louise Buck, and Randy Charlton, for believing in me and for being such a wonderful family.

If one believes that words are acts, as I do, then one must hold writers responsible for what their words do.

– URSULA K. LE GUIN

Dancing at the Edge of the World:

Thoughts on Words, Women, Places

Prolog

The grammarian was choking to death on her own words.

And they were long sharp words, written in a magical language and crushed into a small, spiny ball. Her legs faltered. She fell onto her knees.

Cold autumn wind surged across the tower bridge.

The creature standing beside her covered his face with a voluminous white hood. “Censored already?” he rasped. “Disappointing.”

The grammarian fought for breath. Her head felt as light as silk; her vision burned with gaudy color. The familiar world became foreign.

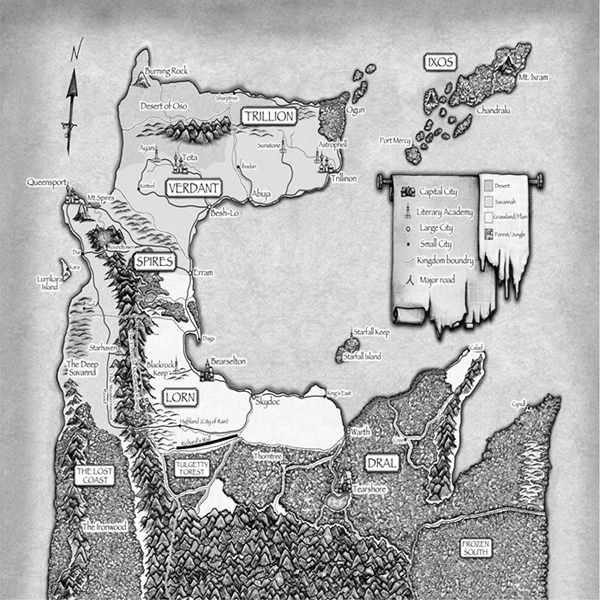

She was kneeling on a stone bridge, seven hundred feet above Starhaven’s walls. Behind her, the academy’s towers stretched into the cold evening sky like a copse of giant trees. At various heights, ribbon-thin bridges spanned the airy gaps between neighboring spires. Before her loomed the dark Pinnacle Mountains.

Dimly, she realized that her confused flight had brought her to the Spindle Bridge.

Her heart began to kick. From here the Spindle Bridge arched a lofty half-mile away from Starhaven to terminate in a mountain’s sheer rock face. It led not to a path or a cave, but to blank stone. It was a bridge to nowhere, offering no chance of rescue or escape.

She tried to scream, but gagged on the words caught in her throat.

To the west, above the coastal plain, the setting sun was staining the sky a molten shade of incarnadine.

The creature robed in white sniffed with disgust. “Pitiful what passes for imaginative prose in this age.” He lifted a pale arm. Two golden sentences glowed within his wrist.

“You are Magistra Nora Finn, Dean of the Drum Tower,” he said. “Do not deny it again, and do not refuse my offer again.” He flicked the glowing sentences into Nora’s chest.

She could do nothing but choke.

“What’s this?” he asked with cold amusement. “Seems my attack stopped that curse in your mouth.” He paused before laughing, low and breathy. “I could make you eat your words.”

Pain ripped down her throat. She tried to gasp.

The creature cocked his head to one side. “But perhaps you’ve changed your mind?”

With five small cracks, the sentences in her throat deconstructed and spilled into her mouth. She fell onto her hands and spat out the silver words. They shattered on the cobblestones. Cold air flooded into her greedy lungs.

“And do not renew your fight,” the creature warned. “I can censor your every spell with this text.”

She looked up and saw that the figure was now holding the golden sentence that ran into her chest. “Which of your students is the one I seek?”

She shook her head.

The creature laughed. “You took our master’s coin, played the spy for him.”

Again, she shook her head.

“Do you need more than gold?” He stepped closer. “I now possess the emerald and so Language Prime. I could tell you the Creator’s first words. You’d find them… amusing.”

“No payment could buy me for you,” Nora said between breaths. “It was different with master; he was a man.”

The creature cackled. “Is that what you think? That he was human?”

The monster’s arm whipped back, snapping the golden sentence taut. The force of the action yanked Nora forward onto her face. Again pain flared down her throat. “No, you stupid sow,” he snarled. “Your former master was not human!”

Something pulled up on Nora’s hair, forcing her to look at her tormentor. A breeze was making his hood ruffle and snap. “Which cacographer do I seek?” he asked.

She clenched her fists. “What do you want with him?”

There was a pause. Only the wind dared make noise. Then the creature spoke. “Him?”

Involuntarily, Nora sucked in a breath. “No,” she said, fighting to make her voice calm. “No, I said ‘with them.’”

The cloaked figure remained silent.

“I said,” Nora insisted, “ ‘What do you want with them?’ Not him. With them.”

Another pause. “A grammarian does not fault on her pronouns. Let us speak of ‘him.’”

“You misheard; I-” The creature disengaged the spell that was holding her head up. She collapsed. “It was different in the dreams,” she murmured into the cobblestones.

The creature growled. “Different because I sent you those dreams. Your students will receive the same: visions of a sunset seen from a tower bridge, dreams of a mountain vista. Eventually they will become curious and investigate.”

Nora let out a tremulous breath. The prophecy had come to pass. How could she have been so blind? What grotesque forces had she been serving?