The Sword of Aldones

by Marion Zimmer Bradley

CHAPTER ONE

We were outstripping the night.

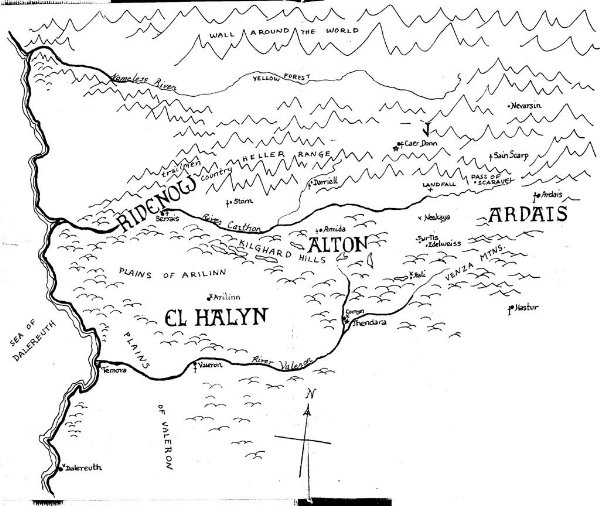

The Southern Cross had made planetfall on Darkover at midnight. There I had embarked on the Terran skyliner that was to take me halfway around a planet; only an hour had passed, but already the thin air was beginning to flush red with a hint of dawn. Under my feet the floor of the big plane tilted slightly as it began to fly aslant down the western ridge of the Hellers. Peak after peak fell away astern, cutting the sparse clouds that capped the snowline; and already my memory was looking for landmarks, although I knew we were too high.

After six years of knocking around half a dozen star-systems, I was going home again; but I felt nothing. Not homesick. Not excited. Not even resentful. I hadn’t wanted to return’ to Darkover, but I hadn’t even cared enough to refuse.

Six years ago I had left Darkover, intending never to return. The Regent’s desperate message had followed me from Terra, to Samarra, to Vainwal. It costs plenty to send a personal message interspace, even over the Terran relay system, and Old Hastur — Regent of the Comyn, Lord of the Seven Domains — hadn’t wasted words in explaining. It had simply been a command. But I couldn’t imagine why they wanted me back. They’d all been glad to see the last of me, when I went.

I turned from the paling light at the window, closing my eyes and pressing my good hand to my temple. The inter-stellar passage, as always, had been made under heavy sedation. Now the dope that the ship’s medic had given me was beginning to wear off; fatigue cut down my barriers; letting in a teasing telepathic trickle of thought.

I could feel the covert stares of the other passengers; at my scarred face; at the arm that ended at the wrist in a folded sleeve; but mostly at what, and who I was. A telepath. A freak. An Alton — one of the Seven Families of the Comyn — that hereditary autarchy which has ruled Darkover since long before our sun faded to red.

And yet, not quite one of them. My father, Kennard Alton — every child on Darkover could repeat the story — had done a shocking, almost a shameful thing. He had married, taken in honorable laran marriage, a Terran woman, kin to the hated Empire people who have overrun the civilized Galaxy.

He had been powerful enough to brazen it out. They had needed my father in Comyn Council. After Old Hastur, he had been the most powerful man in the Comyn. He’d even managed to cram me down their troats. But they’d all been glad when I left Darkover. And now I had come home.

In the seat in front of me, two professorish-looking Earth-men, probably research workers on holiday from mapping and exploring, were debating the old chestnut of origins. One was stubbornly defending the theory of parallel evolutions; the other, the theory that some ancient planet — preferably Earth itself — colonized the whole Galaxy a million years ago. I concentrated on their conversation, trying to shut out awareness of the stares around me. Telepaths are never at ease in crowds.

The Dispersionist brought out all the old arguments for a lost age of star-travel, and the other man was arguing about the nonhuman races and the differing levels of culture on any single planet.

“Darkover, for instance,” he argued. “A planet still in early feudal culture, trying to reconcile itself to the impact of the Terran empire—”

I lost interest. It was amazing, how many Terrans still thought of Darkover as a feudal or barbarian planet. Simply because we retain, not resistance, but indifference to Terran imports of machinery and weapons; because we prefer to ride horses and mules, as an ordinary thing, rather than spend our time in building roads. And because Darkover, bound by the ancient Compact, wants to take no chance of a return to the days of war and mass murder with coward’s weapons. That is the law on all planets of the Darkovan League, and all civilized worlds outside. Who would kill, must come within reach of death. They could talk disparagingly of the code duello, and the feudal system. I’d heard it all, on Terra. But isn’t it more civilized to kill your personal enemy at hand-grips, with sword or knife, than to slay a thousand strangers at a safe distance?

The people of Darkover have held out, better than most, against the glamor of the Terran Empire. I’ve been on other planets, and I’ve seen what happened to most worlds when the Earthmen come in with the lure of a civilization that spans the stars. They don’t subdue new worlds by force of arms. The Earthman can afford to sit back and wait until the native culture simply collapses under their impact. They wait till the planet begs to be taken into the Empire. And sooner or later the planet does — and becomes one more link in the vast, overcentralized monstrosity swallowing world after world.

It hadn’t happened here, not yet.

A man near the front of the cabin rose and made his way toward me; without permission, he swung himself into the empty seat at my side.

“Comyn?” But it wasn’t a question.

The man was tall and sparely built; mountain Darkovan, Cahuenga from the Hellers. His stare dwelt, an instant past politeness, on the scars and the empty sleeve; then he nodded.

“I thought so,” he said. “You were the boy who was mixed up in that Sharra business.”

I felt the blood rise in my face. I had spent six years forgetting the Sharra rebellion — and Marjorie Scott. I would bear the scars forever. Who the hell was this man, to remind me?

“Whatever I was,” I said curtly, “I am not, now. And I don’t remember you.”

“And you an Alton!” he mocked lightly.

“In spite of all scare stories,” I said, “Altons don’t go around casually reading minds. In the first place, it’s hard work. In the second place, most people’s minds are too full of muck. And in the third place,” I added, “we just don’t give a damn.”

He laughed. “I didn’t expect you to recognize me,” he said. “You were drugged and delirious when I saw you last. I told your father that hand would have to come off eventually. I’m sorry I was right about it.” He didn’t sound sorry at all. “I’m Dyan Ardais.”

Now I remembered him, after a fashion, a mountain lord from the far fastnesses of the Hellers. There had never been any love lost, even in the Comyn, between the Altons and the men of the Ardais.

“You travel alone? Where is your father, young Alton?”

“My father died on Vainwal,” I said shortly.

His voice was a purr. “Then welcome, Comyn Alton!” The ceremonial title was a shock as he spoke it. He glanced at the square of paling window.

“We’re coining in to Thendara. Will you travel with me?”

“I expect to be met.” I didn’t, but I had no wish to prolong this chance acquaintance. Dyan bowed, unruffled. “We shall meet in Council,” he said, and added, with lazy elegance, “Oh, and guard your belongings well, Comyn Alton. There are doubtless, some who would like to recover the Sharra matrix.”

He spun round and walked away and I sat slack, in shock. Damn! Had he picked my mind as I sat there? How else had he known? The dirty Cahuenga! Still doped with procalamin as I was, he could have gotten inside my telepathic barriers and out again before I knew it. But would one of the Comyn stoop so far?

I stared after him, furiously; started to rise, and fell back with a jolt; we were losing altitude rapidly. The sign flashed to fasten seat belts; I fumbled at mine, my mind in turmoil.

He had forced memory on me — forced me to remember why I had left Darkover six years ago, scarred and broken and maimed for life. Wounds that had begun to heal, with time and silence, tore at me again. And he had spoken the name of Sharra.