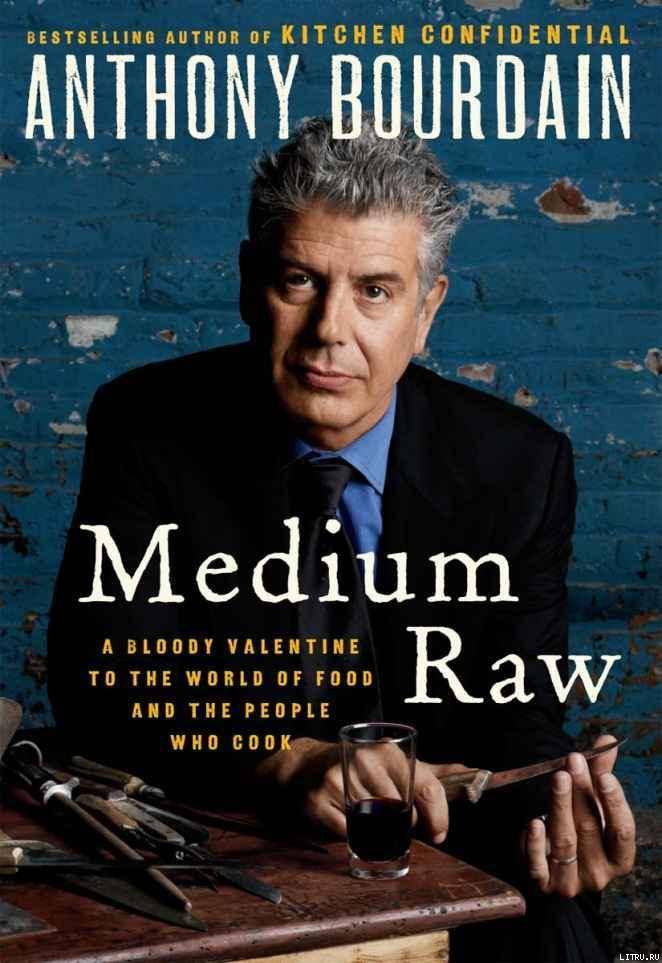

Medium Raw

A Bloody Valentine to the World of Food and the People Who Cook

Anthony Bourdain

To Ottavia

On the whole I have received better treatment in life than the average man and more loving kindness than I perhaps deserved.

—FRANK HARRIS

I recognize the men at the bar. And the one woman. They’re some of the most respected chefs in America. Most of them are French but all of them made their bones here. They are, each and every one of them, heroes to me—as they are to up-and-coming line cooks, wannabe chefs, and culinary students everywhere. They’re clearly surprised to see each other here, to recognize their peers strung out along the limited number of barstools. Like me, they were summoned by a trusted friend to this late-night meeting at this celebrated New York restaurant for ambiguous reasons under conditions of utmost secrecy. They have been told, as I was, not to tell anyone of this gathering. It goes without saying that none of us will blab about it later.

Well…I guess that’s not exactly true.

It’s early in my new non-career as professional traveler, writer, and TV guy, and I still get the vapors being in the same room with these guys. I’m doing my best to conceal the fact that I’m, frankly, star-struck—atwitter with anticipation. My palms are sweaty as I order a drink, and I’m aware that my voice sounds oddly high and squeaky as the words “vodka on the rocks” come out. All I know for sure about this gathering is that a friend called me on Saturday night and, after asking me what I was doing on Monday, instructed me, in his noticeably French accent, that “Tuh-nee…you must come. It will be very special.”

Since leaving all day-to-day responsibilities at my old restaurant, Les Halles, and having had to learn (or relearn)—after a couple of book tours and many travels—how to deal, once again, with civilian society, I now own a couple of suits. I’m wearing one now, dressed appropriately, I think, for a restaurant of this one’s high reputation. The collar on my shirt is too tight and it’s digging into my neck. The knot on my tie, I am painfully aware, is less than perfect. When I arrived at the appointed hour of eleven p.m., the dining room was thinning of customers and I was discreetly ushered here, to the small, dimly lit bar and waiting area. I was relieved that upon laying eyes on me, the maître d’ did not wrinkle his nose in distaste.

I’m thrilled to see X, a usually unflappable figure whom I generally speak of in the same hushed, respectful tones as the Dalai Lama—a man who ordinarily seems to vibrate on a lower frequency than other, more earthbound chefs. I’m surprised to see that he’s nearly as excited as I am, an unmistakable look of apprehension on his face. Around him are some of the second and third waves of Old Guard French guys, some Young Turks—along with a few American chefs who came up in their kitchens. There’s the Godmother of the French-chef mafia…It’s a fucking Who’s Who of the top tier of cooking in America today. If a gas leak blew up this building? Fine dining as we know it would be nearly wiped out in one stroke. Ming Tsai would be the guest judge on every episode of Top Chef, and Bobby Flay and Mario Batali would be left to carve up Vegas between themselves.

A few last, well-fed citizens wander past on their way from the dining room to the street. More than one couple does a double take at the lineup of familiar faces murmuring conspiratorially at the bar. The large double doors to a private banquet room swing open and we are summoned.

There’s a long table, set for thirteen people, in the middle of the room. Against the wall is a sideboard, absolutely groaning under the weight of charcuterie—the likes of which few of us (even in this group) have seen in decades: classic Careme-era terrines of wild game, gallantines of various birds, pâté, and rillettes. The centerpiece is a wild boar pâté en croute, the narrow area between forcemeat and crust filled with clear, amber-tinted aspic. Waiters are pouring wine. We help ourselves.

One by one, we take our seats. A door at the far end of the room opens and we are joined by our host.

It’s like that scene in The Godfather, where Marlon Brando welcomes the representatives of the five families. I almost expect our host to begin with “I’d like to thank our friends the Tattaglias…and our friends from Brooklyn…” It’s a veritable Apalachin Conference. By now, word of what we’re about to eat is getting around the table, ratcheting up the level of excitement.

There is a welcome—and a thank-you to the person who procured what we are about to eat (and successfully smuggled it into the country). There is a course of ravioli in consommé (quite wonderful) and a civet of wild hare. But these go by in a blur.

Our dirty plates are removed. The uniformed waiters, struggling to conceal their smiles, reset our places. Our host rises and a gueridon is rolled out bearing thirteen cast-iron cocottes. Inside each, a tiny, still-sizzling roasted bird—head, beak, and feet still attached, guts intact inside its plump little belly. All of us lean forward, heads turned in the same direction as our host high pours from a bottle of Armagnac, dousing the birds—then ignites them. This is it. The grand slam of rare and forbidden meals. If this assemblage of notable chefs is not reason enough to pinch myself, then this surely is. This is a once-in-a-fucking-lifetime meal—a never-in-a-lifetime meal for most mortals—even in France! What we’re about to eat is illegal there as it’s illegal here. Ortolan.

The ortolan, or emberiza hortulana, is a finch-like bird native to Europe and parts of Asia. In France, where they come from, these little birdies can cost upwards of 250 bucks a pop on the black market. It is a protected species, due to the diminishing number of its nesting places and its shrinking habitat. Which makes it illegal to trap or to sell anywhere. It is also a classic of country French cuisine, a delight enjoyed, in all likelihood, since Roman times. Rather notoriously, French president François Mitterrand, on his deathbed, chose to eat ortolan as his putative last meal, and a written account of this event remains one of the most lushly descriptive works of food porn ever committed to paper. To most, I guess, it might seem revolting: a desperately ill old man, struggling to swallow an unctuous mouthful of screamingly hot bird guts and bone bits. But to chefs? It’s wank-worthy, a description of the Holy Grail, the Great Unfinished Business, the Thing That Must Be Eaten in order that one may state without reservation that one is a true gastronome, a citizen of the world, a chef with a truly experienced palate—that one has really been around.

As the story goes, the birds are trapped in nets, then blinded by having their eyes poked out—to manipulate the feeding cycle. I have no doubt that at various times in history this was true. Labor laws being what they are in Europe these days, it is apparently no longer cost-effective to employ an eye-gouger. A simple blanket or a towel draped over the cage has long since replaced this cruel means of tricking the ortolan into continuingly gorging itself on figs, millet, and oats.