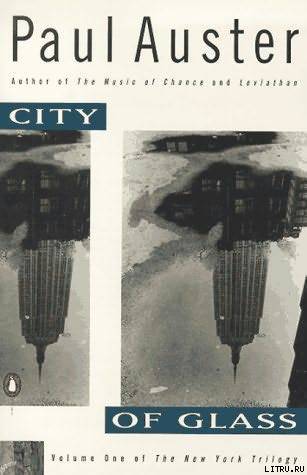

Paul Auster

City of Glass

The first book in the New York Trilogy series, 1985

1

IT was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not. Much later, when he was able to think about the things that happened to him, he would conclude that nothing was real except chance. But that was much later. In the beginning, there was simply the event and its consequences. Whether it might have turned out differently, or whether it was all predetermined with the first word that came from the stranger's mouth, is not the question. The question is the story itself, and whether or not it means something is not for the story to tell.

As for Quinn, there is little that need detain us. Who he was, where he came from, and what he did are of no great importance. We know, for example, that he was thirty-five years old. We know that he had once been married, had once been a father, and that both his wife and son were now dead. We also know that he wrote books. To be precise, we know that he wrote mystery novels. These works were written under the name of William Wilson, and he produced them at the rate of about one a year, which brought in enough money for him to live modestly in a small New York apartment. Because he spent no more than five or six months on a novel, for the rest of the year he was free to do as he wished. He read many books, he looked at paintings, he went to the movies. In the summer he watched baseball on television; in the winter he went to the opera. More than anything else, however, what he liked to do was walk. Nearly every ay, rain or shine, hot or cold, he would leave his apartment to walk through the city-never really going anywhere, but simply going wherever his legs happened to take him.

New York was an inexhaustible space, a labyrinth of endless steps, and no matter how far he walked, no matter how well he came to know its neighborhoods and streets, it always left him with the feeling of being lost. Lost, not only in the city, but within himself as well. Each time he took a walk, he felt as though he were leaving himself behind, and by giving himself up to the movement of the streets, by reducing himself to a seeing eye, he was able to escape the obligation to think, and this, more than anything else, brought him a measure of peace, a salutary emptiness within. The world was outside of him, around him, before him, and the speed with which it kept changing made it impossible for him to dwell on any one thing for very long. Motion was of the essence, the act of putting one foot in front of the other and allowing himself to follow the drift of his own body. By wandering aimlessly, all places became equal, and it no longer mattered where he was. On his best walks, he was able to feel that he was nowhere. And this, finally, was all he ever asked of things: to be nowhere. New York was the nowhere he had built around himself, and he realized that he had no intention of ever leaving it again.

In the past, Quinn had been more ambitious. As a young man he had published several books of poetry, had written plays, critical essays, and had worked on a number of long translations. But quite abruptly, he had given up all that. A part of him had died, he told his friends, and he did not want it coming back to haunt him. It was then that he had taken on the name of William Wilson. Quinn was no longer that part of him that could write books, and although in many ways Quinn continued to exist, he no longer existed for anyone but himself.

He had continued to write because it was the only thing he felt he could do. Mystery novels seemed a reasonable solution. He had little trouble inventing the intricate stories they required, and he wrote well, often in spite of himself, as if without having to make an effort. Because he did not consider himself to be the author of what he wrote, he did not feel responsible for it and therefore was not compelled to defend it in his heart. William Wilson, after all, was an invention, and even though he had been born within Quinn himself, he now led an independent life. Quinn treated him with deference, at times even admiration, but he never went so far as to believe that he and William Wilson were the same man. It was for this reason that he did not emerge from behind the mask of his pseudonym. He had an agent, but they had never met. Their contacts were confined to the mail, for which purpose Quinn had rented a numbered box at the post office. The same was true of the publisher, who paid all fees, monies, and royalties to Quinn through the agent. No book by William Wilson ever included an author's photograph or biographical note. William Wilson was not listed in any writers' directory, he did not give interviews, and all the letters he received were answered by his agent's secretary. As far as Quinn could tell, no one knew his secret. In the beginning, when his friends learned that he had given up writing, they would ask him how he was planning to live. He told them all the same thing: that he had inherited a trust fund from his wife. But the fact was that his wife had never had any money. And the fact was that he no longer had any friends.

It had been more than five years now. He did not think about his son very much anymore, and only recently he had removed the photograph of his wife from the wall. Every once in a while, he would suddenly feel what it had been like to hold the three-year-old boy in his arms but that was not exactly thinking, nor was it even remembering. It was a physical sensation, an imprint of the past that had been left in his body, and he had no control over it. These moments came less often now, and for the most part it seemed as though things had begun to change for him. He no longer wished to be dead. At the same time, it cannot be said that he was glad to be alive. But at least he did not resent it. He was alive,.and the stubbornness of this fact had little by little begun to fascinate him-as if he had managed to outlive himself, as if he were somehow living a posthumous life. He did not sleep with the lamp on anymore, and for many months now he had not remembered any of his dreams.

It was night. Quinn lay in bed smoking a cigarette, listening to the rain beat against the window. He wondered when it would stop and whether he would feel like taking a long walk or a short walk in the morning. An open copy of Marco Polo's Travels lay face down on the pillow beside him. Since finishing the latest William Wilson novel two weeks earlier, he had been languishing. His private-eye narrator, Max Work, had solved an elaborate series of crimes, had suffered through a number of beatings and narrow escapes, and Quinn was feeling somewhat exhausted by his efforts. Over the years, Work had become very close to Quinn. Whereas William Wilson remained an abstract figure for him, Work had increasingly come to life. In the triad of selves that Quinn had become, Wilson served as a kind of ventriloquist, Quinn himself was the dummy, and Work was the animated voice that gave purpose to the enterprise. If Wilson was an illusion, he nevertheless justified the lives of the other two. If Wilson did not exist, he nevertheless was the bridge that allowed Quinn to pass from himself into, Work. And little by little, Work had become a presence in Quinn's life, his interior brother, his comrade in solitude.

Quinn picked up the Marco Polo and started reading the first page again. "We will set down things seen as seen, things heard as heard, so that our book may be an accurate record, free from any sort of fabrication. And all who read this book or hear it may do so with full confidence, because it contains nothing but the truth." Just as Quinn was beginning to ponder the meaning of these sentences, to turn their crisp assurances over in his mind, the telephone rang. Much later, when he was able to reconstruct the events of that night, he would remember looking at the clock, seeing that it was past twelve, and wondering why someone should be calling him at that hour. More than likely, he thought, it was bad news. He climbed out of bed, walked naked to the telephone, and picked up the receiver on the second ring.