DUDLEY POPE

The Ramage Touch

For Roz and David

CHAPTER ONE

When Ramage eventually succeeded in focusing the nightglass on the two distant ships, because it showed an inverted image they were faintly outlined against the stars and looked like bats hanging side by side and upside down from a beam.

Southwick and Aitken stood beside him at the quarterdeck rail attempting to conceal their impatience. The vessels had been spotted ten minutes earlier by a masthead lookout, who had seen them momentarily against a rising star. The master was the first to give up trying. "Frigates, are they, sir?"

"No."

"Nor ships of the line ?" Southwick's voice indicated more hopefulness than fear, even though the Calypso herself was only a frigate.

"No," Ramage said sarcastically, although secretly amused at the old man's pugnacious attitude, which was obviously under a strain because they had been back in the Mediterranean for several days now without firing a gun, except at exercise. "As soon as I identify them, I'll tell you. Or you can take this -" he offered the nightglass, which was the only one left in the ship because the other had been broken within hours of leaving Gibraltar, "and go aloft to look for yourself."

Southwick patted his paunch and grinned in the darkness. "I'll wait, sir. Sorry, but it makes me impatient . . ."

"Don't get too excited," Ramage warned. "Although they're damn'd odd looking ships they're small. And they're steering in for the coast."

"You mean we won't catch 'em before they reach it, sir?"

"Not with this whiffling wind. Either they've spotted us and are going to run up on the beach and set themselves on fire because they can't escape, or they haven't and, because they can't make headway against wind and current, have decided to edge in and anchor in the lee of Punta Ala. They can stay there until the wind strengthens, or veers more to the north. In fact, I doubt if they've seen us and are waiting for a veer. They must be as sick as we are of tacking in this light southerly."

Ramage looked up at the sails, great rectangles blotting out whole constellations of stars, but there was so little wind that there was only a slight belly in the canvas. For once he was grateful that for the moment there was not enough chilly downdraught to make him turn up the collar of his boatcloak. He could see the quartermaster was dancing from one side of the binnacle to the other, watching the luffs, while the men at the wheel felt the ship almost dead in the water.

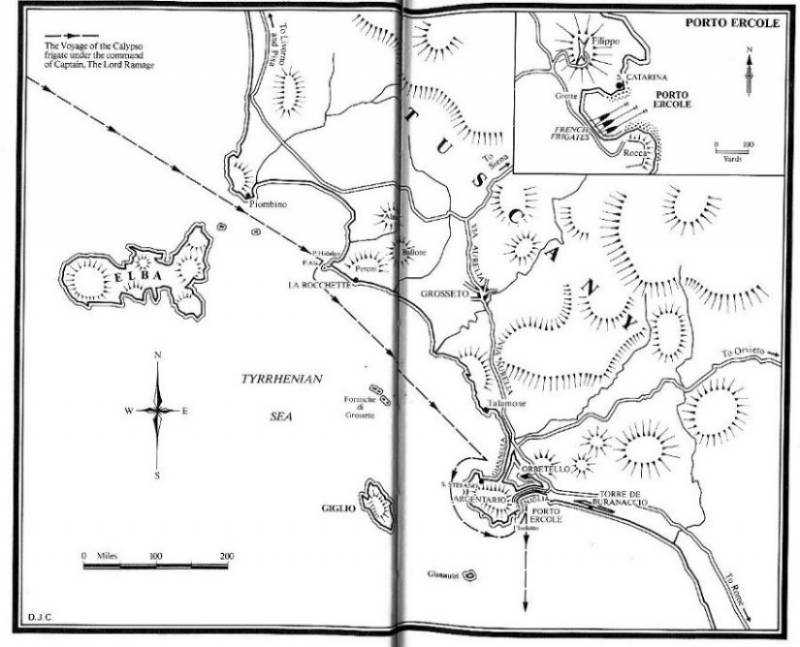

Once again Ramage steadied his elbows on the rail and once again held his breath to lessen the movement of the glass as he pressed it to his eye. The eastern horizon was jagged with cliffs and hills, black humps and odd shapes that made up this part of the Tuscan coast. Yes, there they were, tiny, angular black bruises against the night sky. The strangest thing was the position of the masts, although their angle made it certain they were steering in for the north side of Punta Ala ... It was no good straining his eyes any longer: at that moment the ships slid into the dark background of the Tuscan hills as though a door had closed behind them. Ramage put the glass in the binnacle box drawer.

"We'll go in after them," Ramage said briskly, explaining that they were out of sight.

"Shall I send the men to quarters, sir?" Aitken asked eagerly, reaching for the speaking trumpet.

"There's no hurry; it'll take us an hour or more to get within sight of the beach. When is moonrise?"

"Another hour," Southwick said promptly, having just put his watch back in its pocket. "And it'll be a few minutes late by the time it has climbed up from behind those mountains. The - er, those two ships, sir . . ."

"The Devil only knows," Ramage said. "There are so many odd local rigs out here in the Mediterranean, from caiques to xebecs, that I can't even guess in this light. These two look like ketches, except for the masts: they are set so far aft. The mainmast is where you'd expect the foremast to be stepped; the main looks like a mizen. They seem to have tall rigs considering the length of their hulls, and unless the light was playing tricks they have long jibbooms."

"Could they be timber carriers?" It was a sensible question from Southwick because a ship carrying lumber needed long hatches to load decent lengths in the hold.

Ramage shook his head. "Not in the Mediterranean. In the Baltic and North Sea, with long mast timber being moved, yes; but down here the trade is in what the shipwrights call 'short stuff'; larch and the like, and the occasional oak."

"Wine?" Aitken asked, managing to put into the word all the disapproval of a stern Scottish upbringing.

"Neapolitan winecarriers?" Ramage expanded the question, knowing Aitken was a stranger to the Mediterranean. "Or even olive oil? No, I've been thinking of them but they're beamier; they sit squat in the water like Newcastle colliers and don't have a very high rig. In fact I doubt if they could maintain steerage way in this breeze."

"They must be transports of some sort," Southwick grumbled, removing his hat and shaking out his flowing white hair as though spinning a dry mop. "Troops, guns, horses, infantry, powder and shot . . . The French have to supply the garrisons in Italy."

Ramage had already considered salt fish being brought down from Genoa or Leghorn, and military cargoes that could be travelling up and down the coast. He had a vivid picture of the Calypso frigate boarding one French transport and discovering at the last moment that she had five hundred well-trained troops waiting on board, with another five hundred in the consort coming up to the rescue. Likewise a few broadsides fired at close range into a transport laden with casks of gunpowder might well make a very loud bang that none of them would survive to hear for more than a second.

There was only one way of finding out what it was all about. "Allow a knot and a half of northgoing current," he told Southwick, "and give us a course for Punta Ala. If you don't see those ships bursting into flames before moonrise, you can reckon they're just anchored to wait for a wind veer."

Still thinking of the strange shape of the two ships after they had slid into the shadows, Ramage reflected that every country's coast had its own characteristic smell and noise when approached from seaward at night. With experience you can recognize it. The Italian coastline here just south of Elba was just as he remembered it from three or four years ago - but very different from the West Indies he had just left.

Oddly enough there was not so much physical difference in daylight: the high but rounded, breast-shaped Tuscan hills and more distant mountains, scorched brown by the summer drought and with trees only on the lower slopes, were very similar to those of several West Indian islands. Apart from the startling blue of the Caribbean sea and sky, the Virgin Islands, St Christopher, Nevis, St Bartholomew, St Martin and even Guadeloupe and Martinique, could have been part of Tuscany - except, of course, for the noises and smells.

In Italy the carbonaio was always busy cutting thick shrubs and lopping branches from trees and at night he tamped down his ovens with turf so that random draughts did not make too much heat and burn the wood to ash instead of baking it into charcoal. The smoke coming up from the hummocks, like autumn mist starting in a valley, drifted off to leeward with its own distinctive smell: of neither bonfire nor blaze, open grate nor bushfire. When the offshore breeze came up at night in settled weather the smell of the charcoal burning could be detected many miles out to sea, a signpost pointing homeward for the local fishermen but a warning signal to the unwary navigator. Mingling with it but sweeter yet sharper than the charcoal was the smell of herbs: sage, which covered many of the hills, thyme, rosemary and origano.