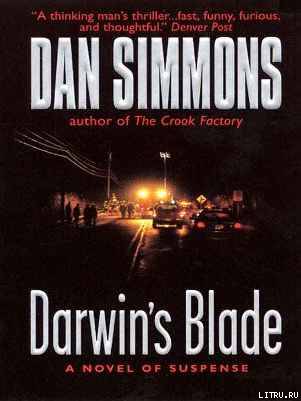

Darwin’s Blade

By

DAN SIMMONS

This book is dedicated to Wayne Simmons and Stephen King. For my brother Wayne, who is involved with accident investigation every day, admiration that your sense of humor has survived; for Steve, who felt the cutting edge of Darwin’s blade via someone else’s lethal stupidity, gratitude that you’re still with us and willing to tell us more tales by the campfire.

Occam’s Razor: All other things being equal, the simplest solution is usually the correct one.

—William of Occam, 14th Century

Darwin’s Blade: All other things being equal, the simplest solution is usually stupidity.

—Darwin Minor, 21st Century

1

“A is for Hole”

The phone rang a few minutes after four in the morning. “You like accidents, Dar. You owe it to yourself to come see this one.”

“I don’t like accidents,” said Dar. He did not ask who was calling. He recognized Paul Cameron’s voice even though he and Cameron had not been in touch for over a year. Cameron was a CHP officer working out of Palm Springs.

“All right, then,” said Cameron, “you like puzzles.”

Dar swiveled to read his clock. “Not at four-oh-eight A.M.,” he said.

“This one’s worth it.” The connection sounded hollow, as if it were a radio patch or a cell phone.

“Where?”

“Montezuma Valley Road,” said Cameron. “Just a mile inside the canyon, where S22 comes out of the hills into the desert.”

“Jesus Christ,” muttered Dar. “You’re talking Borrego Springs. It would take me more than ninety minutes to get there.”

“Not if you drive your black car,” said Cameron, his chuckle blending with the rasp and static of the poor connection.

“What kind of accident would bring me almost all the way to Borrego Springs before breakfast?” said Dar, sitting up now. “Multiple vehicle?”

“We don’t know,” said Officer Cameron. His voice still sounded amused.

“What do you mean you don’t know? Don’t you have anyone at the scene yet?”

“I’m calling from the scene,” said Cameron through the static.

“And you can’t tell how many vehicles were involved?” Dar found himself wishing that he had a cigarette in the drawer of his bedside table. He had given up smoking ten years earlier, just after the death of his wife, but he still got the craving at odd times.

“We can’t even ascertain beyond a reasonable doubt what kind of vehicle or vehicles was or were involved,” said Cameron, his voice taking on that official, strained-syntax, preliterate lilt that cops used when speaking in their official capacity.

“You mean what make?” said Dar. He rubbed his chin, heard the sandpaper scratch there, and shook his head. He had seen plenty of high-speed vehicular accidents where the make and model of the car were not immediately apparent. Especially at night.

“I mean we don’t know if this is a car, more than one car, a plane, or a fucking UFO crash,” said Cameron. “If you don’t see this one, Darwin, you’ll regret it for the rest of your days.”

“What do you…” Dar began, and stopped. Cameron had broken the connection. Dar swung his legs over the edge of the bed, looked out at the dark beyond the glass of his tall condo windows, muttered, “Shit,” and got up to take a fast shower.

It took him two minutes less than an hour to drive there from San Diego, pushing the Acura NSX hard through the canyon turns, slamming it into high gear on the long straights, and leaving the radar detector in the tiny glove compartment because he assumed that all of the highway patrol cars working S22 would be at the scene of the accident. It was paling toward sunrise as he began the long 6-percent grade, four-thousand-foot descent past Ranchita toward Borrega Springs and the Anza-Borrega Desert.

One of the problems with being an accident reconstruction specialist, Dar was thinking as he shifted the NSX into third and took a decreasing-radius turn effortlessly, with only the throaty purr of the exhaust marking the deceleration and then the shift back up to speed, is that almost every mile of every damned highway holds the memory of someone’s fatal stupidity. The NSX roared up a low rise in the predawn glow and then growled down the long, twisty descent into the canyon some miles below.

There, thought Dar, glancing quickly at an unremarkable stretch of old single-height guardrail set on wooden posts flashing past on the outside of a tight turn. Right there.

A little more than five years ago, Dar had arrived at that point only thirty-five minutes after a school bus had struck that stretch of old guardrail, scraped along it for more than sixty feet, and plunged over the embankment, rolled three times down the steep, boulder-strewn hillside, and had come to rest on its side, with its shattered roof in the narrow stream below. The bus had been owned by the Desert Springs School District and was returning from an “Eco-Week” overnight camping trip in the mountains, carrying forty-one sixth-grade students and two teachers. When Dar arrived, ambulances and Flight-For-Life helicopters were still carrying off seriously injured children, a mob of rescue workers was handing litters hand over hand up the rocky slope, and yellow plastic tarps covered at least three small bodies on the rocks below. When the final tally came in, six children and one teacher were dead, twenty-four students were seriously injured—including one boy who would be a paraplegic for the rest of his life—and the bus driver received cuts, bruises, and a broken left arm.

Dar was working for the NTSB then—it was the year before he quit the National Transportation Safety Board to go to work as an independent accident reconstruction specialist. That time the call came to his condo in Palm Springs.

For days after the accident, Dar watched the media coverage of the “terrible tragedy.” The L.A. television stations and newspapers had decided early on that the bus driver was a heroine—and their coverage reflected that stance. The driver’s postcrash interview and other eyewitness testimony, including that of the teacher who had been sitting directly behind one of the children who had perished, certainly suggested as much. All agreed that the brakes had failed about one mile after the bus began its long, steep descent. The driver, a forty-one-year-old divorced mother of two, had shouted at everyone to hang on. What followed was a terrifying six-mile Mad Mouse ride with the driver doing her best to keep the careening bus on the road, the brakes smoking but obviously not slowing the vehicle enough, children flying out of their seats on the sharp turns, and then the final crash, grinding, and plummet over the embankment. All agreed that there was nothing the driver could have done, that once the brakes had failed it had been a miracle that she had kept the bus on the road as long as she had.

Dar read the editorials proclaiming that the driver was the kind of hero for whom no tribute could be too great. Two Los Angeles TV stations carried live coverage of the school board meeting during which parents of the surviving children gave testimonials to the driver’s heroic attempts to save the bus under “impossible circumstances.” The NBC Nightly News did a four-minute special profile piece on this driver and other school bus drivers who had been injured or killed “in the line of duty.” Tom Brokaw called this driver and others like her “America’s unsung heroes.”

Meanwhile, Dar gathered information.

The school bus was a 1989 model TC-2000 manufactured by the Blue Bird Body Company and purchased new by the Desert Springs School District. It had power steering, a diesel engine, and a model AT 545 four-speed automatic transmission from the Allison Transmission Division of General Motors. It was also equipped with a Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) 121-approved dual air-mechanical, cam-and-drum brake system that had front axle clamp type-20 brake chambers and rear axle clamp type-24/30 and emergency/parking brake chambers. All of the brakes had 5.5-inch manual slack adjusters.