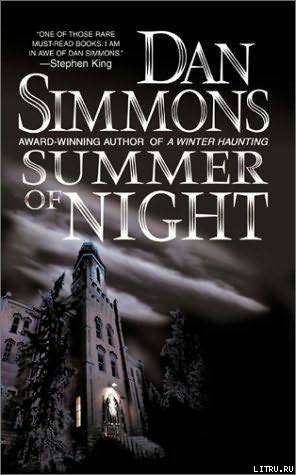

Summer of Night

Dan Simmons

Old Central School still stood upright, holding its secrets and silences firmly within. Eighty-four years of chalkdust floated in the rare shafts of sunlight inside while the memories of more than eight decades of varnishings rose from the dark stairs and floors to tinge the trapped air with the mahogany scent of coffins. The walls of Old Central were so thick that they seeded to absorb sounds while the tall windows, their glass warped and distorted by age and gravity, tinted the air with a sepia tiredness.

Time moved more slowly in Old Central, if at all. Footsteps echoed along corridors and up stairwells, but the sound seemed muted and out of synch with any motion amidst the shadows.

The cornerstone of Old Central had been laid in 1876, the year that General Custer and his men had been slaughtered near the Little Bighorn River far to the west, the year that the first telephone had been exhibited at the nation's Centennial in Philadelphia far to the east. Old Central School was erected in Illinois, midway between the two events but far from any flow of history.

By the spring of 1960, Old Central School had come to resemble some of the ancient teachers who had taught in her: too old to continue but too proud to retire, held stiffly upright by habit and a simple refusal to bend. Barren herself, a fierce old spinster, Old Central borrowed other people's children over the decades.

ONE

Girls played with dolls in the shadows of her classrooms and corridors and later died in childbirth. Boys ran shouting through her hallways, sat in punishment through the growing darkness of winter afternoons in her silent rooms, and were buried in places never mentioned in their geography lessons: San Juan Hill, Belleau Wood, Okinawa, Omaha Beach, Pork Chop Hill, and Inchon.

Originally Old Central had been surrounded by pleasant young saplings, the closer elms throwing shade on the lower classrooms in the warm days of May and September. But over the years the closer trees died and the perimeter of giant elms which lined Old Central's city block like silent sentinels grew calcified and skeletal with age and disease. A few were cut down and carted away but the majority remained, the shadows of their bare branches reaching across the playgrounds and playing fields like gnarled hands groping for Old Central herself.

Visitors to the small town of Elm Haven who left the Hard Road and wandered the two blocks necessary to see Old Central frequently mistook the building for an oversized courthouse or some misplaced county building bloated by hubris to absurd dimensions. After all, what function in this decaying town of eighteen hundred people could demand this huge three-story building sitting in a block all its own? Then the travelers would see the playground equipment and realize that they were looking at a school. A bizarre school: its ornate bronze and copper belfry gone green with verdigris atop its black, steep-pitched roof more than fifty feet above the ground; its Richardsonian Romanesque stone arches curling like serpents above twelve-foot-tall windows; its scattering of other round and oval stained-glass windows suggesting some absurd hybrid between cathedral and school; its Cha-teauesque, gabled roof dormers peering out above third-story eaves; its odd volutes looking like scrollworks turned to stone above recessed doors and blind-looking windows; and, striking the viewer most disturbingly, its massive, misplaced, and somehow ominous size. Old Central, with its three rows of windows rising four stories, its overhanging eaves and gabled dormers, its hipped roof and scabrous belfry, seemed much too large a school for such a modest town. If the traveler had any knowledge of architecture at all, he or she would stop on the quiet asphalt street, step out of the car, gape, and take a picture.

But even as the picture was being snapped, an observant viewer would notice that the tall windows were great, black holes-as if they were designed to absorb light rather than admit or reflect it-and that the Richardsonian Romanesque, Second Empire, or Italianate touches were grafted onto a brutal and common style of architecture which might be described as Midwestern School Gothic, and that the final sense was not of a striking building, or even of a true architectural curiosity, but only of an oversized and schizophrenic mass of brick and stone capped with a belfry obviously designed by a madman.

A few visitors, ignoring or defying a growing feeling of unease, might make local inquiries or even go so far as drive to Oak Hill, the county seat, to look up records on Old Central. There they would find that the school had been part of a master plan eighty-some years earlier to build five great schools in the county--Northeast, Northwest, Central, Southeast, and Southwest. Of these, Old Central had been the first and only school constructed.

Elm Haven in the 1870s had been larger than it was now in 1960, thanks largely to the railroad (now in disuse) and a major influx of immigrant settlers brought south from Chicago by ambitious city planners. From a county population of 28,000 in 1875, the area had dwindled to fewer than 12,000 in the 1960 census, most of them fanners. Elm Haven had boasted 4,300 people in 1875 and Judge Ashley, the millionaire behind the settlement plans and the building of Old Central, had predicted that the town would soon pass Peoria in population and someday rival Chicago.

The architect Judge Ashley had brought in from somewhere back east-one Solon Spencer Alden-had been a student of both Henry Hobson Richardson and R. M. Hunt and his resultant architectural nightmare reflected the darker elements of the coming Romanesque Revival without the sense of grandeur or public purpose those Romanesque buildings might offer.

Judge Ashley had insisted-and Elm Haven had agreed-that the school would be built to accommodate the later, larger generations of schoolchildren which would be drawn to Creve Coeur County. Thus the building had housed not only K-6 classrooms but the high-school classrooms on the third floor-used only until the Great War-and sections which were meant to be used as the city library and even serve as space for a college when the need arrived.

No college ever came to Creve Coeur County or Elm Haven. Judge Ashley's great home at the end of Broad Avenue burned to the ground after his son went bankrupt in the Recession of 1919. Old Central remained an elementary school through the years, serving fewer and fewer children as people left the area and consolidated schools were built in other sections of the county.

The high-school level on the third floor became redundant when the real high school opened in Oak Hill in 1920. Its furnished rooms were closed off to cobwebs and darkness. The city library was moved out of the arched Elementary section in 1939, and the upper mezzanine of shelves stood largely empty, staring down at the few remaining students who moved through the darkened halls and too-broad stairways and basement catacombs like refugees in some long-abandoned city from an incomprehensible past.

Finally, in the fall of 1959, the new city council and the Creve Coeur County School District decided that Old Central had outlived its usefulness, that the architectural monstrosity-even in its eviscerated state-was too difficult to heat and maintain, and that the final 134 Elm Haven students in grades K-6 would be moved to the new consolidated school near Oak Hill in the fall of 1960.

But in the spring of 1960, on the last day of school, only hours before she would be forced into final retirement, Old Central School still stood upright, holding its secrets and silences firmly within.