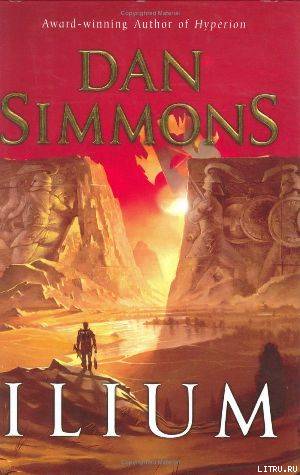

ILIUM

DAN SIMMONS

This novel is dedicated to Wabash College—its men, its faculty, and its legacy

—Andrew Marvell’s “The Garden”

Of possessions

cattle and fat sheep are things to be had for the lifting,

and tripods can be won, and the tawny high heads of horses,

but a man’s life cannot come back again, it cannot be lifted

nor captured again by force, once it has crossed the teeth’s barrier.

—Achilles in Homer’s The Iliad,

Book IX, 405–409

A bitter heart that bides its time and bites.

—Caliban in Robert Browning’s

“Caliban upon Setebos”

Acknowledgments

While many translations of the Iliad were referred to in preparation for the writing of this novel, I would specifically like to acknowledge the following translators—Robert Fagles, Richmond Lattimore, Alexander Pope, George Chapman, Robert Fitzgerald, and Allen Mandelbaum. The beauty of their translations is manifold and their talent is beyond this writer’s comprehension.

For ancillary poetry or imaginative Iliad -related prose which helped shape this volume, I would especially like to acknowledge the work of W. H. Auden, Robert Browning, Robert Graves, Christopher Logue, Robert Lowell, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

For research and commentary on the Iliad and Homer, I would like to acknowledge the work of Bernard Knox, Richmond Lattimore, Malcolm M. Willcock, A.J.B. Wace, F. H. Stubbings, C. Kerenyi, and members of the Homeric scholia too numerous to mention.

For insightful commentary on Shakespeare and Browning’s “Caliban upon Setebos,” I gratefully acknowledge the writings of Harold Bloom, W. H. Auden, and the editors of the Norton Anthology of English Literature. For an insight into Auden’s interpretation of “Caliban upon Setebos” and other aspects of Caliban, I refer readers to Edward Mendelson’s Later Auden.

“Mahnmut’s” insights into the sonnets of Shakespeare were largely guided by Helen Vendler’s wonderful The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Many of “Orphu of Io’s” comments on the work of Marcel Proust were inspired by Roger Shattuck’s Proust’s Way: A Field Guide to In Search of Lost Time.

To readers interested in emulating Mahnmut’s Bardolotous love of Shakespeare, I would recommend Harold Bloom’s Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, Herman Gollob’s Me and Shakespeare: Adventures with the Bard, and Shakespeare: A Life by Park Honan .

For detailed maps of Mars (before the terraforming), I owe a great debt of gratitude to NASA, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Uncovering the Secrets of the Red Planet, published by the National Geographic Society, edited by Paul Raeburn, with forward and commentary by Matt Golombeck. Scientific American has been a rich source of detail, and acknowledgment should go to such articles as “The Hidden Ocean of Europa,” by Robert T. Pappalardo, James W. Head, and Ronald Greeley (October 1999), “Quantum Teleportation” by Anton Zeilinger (April 2000), and “How to Build a Time Machine” by Paul Davies (September 2002).

Finally, my thanks to Clee Richeson for details on how to build a homemade casting furnace with a wooden cupola.

Author’s Note

When my kid brother and I used to take our toy soldiers out of the box, we had no problem playing with our blue and gray Civil War soldiers alongside our green World War II guys. I prefer to think of this as a precocious example of what John Keats called “Negative Capability.” (We also had a Viking, a cowboy, an Indian, and a Roman Centurion flinging grenades, but they were in our Time Commando Platoon. Some anomalies demand what the Hollywood people insist on calling a backstory.)

With Ilium, however, I thought a certain consistency was required. Those readers who teethed, as I did, on Richmond Lattimore’s wonderful 1951 translation of the Iliad will notice that Hektor, Achilleus, and Aias have become Hector, Achilles, and Ajax (Big and Little). In this I agree with Robert Fagles in his 1990 translation that while these more latinized versions are farther from the Greek—Hektor versus Akhilleus and the Akhaians and the Argeioi—the more faithful version sometimes sounds like a cat coughing up a hairball. As Fagles points out, no one can claim perfect consistency, and it tends to read more smoothly when we return to the traditional practice of the English poets by using Latinate spellings and even modern English forms for the heroes and their gods.

The exception to this, again as per Fagles, is when we would have Ulysses instead of Odysseus or, say, Minerva replacing Athena. Alexander Pope in his incredibly beautiful translation of the Iliad into heroic couplets had no problem with “Jupiter” or “Jove” ripping Ares (not Mars) a new one, but my Negative Capability falters here. Sometimes, it seems, you have to play with just the green guys.

Note: For those readers who, like me, have problems in an epic tale telling the gods, goddesses, heroes, and other characters apart without a scorecard, I would refer you to our dramatis personae beginning on page 573 .

1

The Plains of Ilium

Rage.

Sing, O Muse, of the rage of Achilles, of Peleus’ son, murderous, man-killer, fated to die, sing of the rage that cost the Achaeans so many good men and sent so many vital, hearty souls down to the dreary House of Death. And while you’re at it, O Muse, sing of the rage of the gods themselves, so petulant and so powerful here on their new Olympos, and of the rage of the post-humans, dead and gone though they might be, and of the rage of those few true humans left, self-absorbed and useless though they may have become. While you are singing, O Muse, sing also of the rage of those thoughtful, sentient, serious but not-so-close-to-human beings out there dreaming under the ice of Europa, dying in the sulfur-ash of Io, and being born in the cold folds of Ganymede.

Oh, and sing of me, O Muse, poor born-again-against-his-will Hockenberry—poor dead Thomas Hockenberry, Ph.D., Hockenbush to his friends, to friends long since turned to dust on a world long since left behind. Sing of my rage, yes, of my rage, O Muse, small and insignificant though that rage may be when measured against the anger of the immortal gods, or when compared to the wrath of the god-killer, Achilles.

On second thought, O Muse, sing of nothing to me. I know you. I have been bound and servant to you, O Muse, you incomparable bitch. And I do not trust you, O Muse. Not one little bit.

If I am to be the unwilling Chorus of this tale, then I can start the story anywhere I choose. I choose to start it here.

It is a day like every other day in the more than nine years since my rebirth. I awaken at the Scholia barracks, that place of red sand and blue sky and great stone faces, am summoned by the Muse, get sniffed and passed by the murderous cerberids, am duly carried the seventeen vertical miles to the grassy summits of Olympos via the high-speed east-slope crystal escalator and—once reported in at the Muse’s empty villa—receive my briefing from the scholic going off-shift, don my morphing gear and impact armor, slide the taser baton into my belt, and then QT to the evening plains of Ilium.