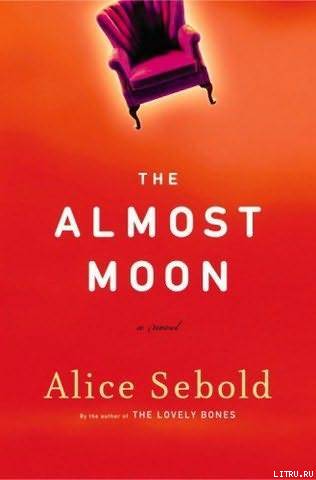

Alice Sebold

The Almost Moon

Copyright © 2007 by Alice Sebold

Always, Glen

ONE

When all is said and done, killing my mother came easily. Dementia, as it descends, has a way of revealing the core of the person affected by it. My mother’s core was rotten like the brackish water at the bottom of a weeks-old vase of flowers. She had been beautiful when my father met her and still capable of love when I became their late-in-life child, but by the time she gazed up at me that day, none of this mattered.

If I hadn’t picked up my ringing phone, Mrs. Castle, my mother’s unlucky neighbor, would have continued down the list of emergency numbers posted on my mother’s almond-colored fridge. But within the hour, I found myself rushing over to the house where I was born.

It was a cool October morning. When I arrived, my mother was sitting upright in her wing chair, wrapped in a mohair shawl, and mumbling to herself. Mrs. Castle said my mother hadn’t recognized her that morning when she’d brought the paper to the door.

“She tried to slam the door on me,” Mrs. Castle said. “She screamed like I was scalding her. It was the most pitiful thing imaginable.”

My mother sat, a totemic presence, in the flocked red-and-white wing chair in which she’d spent the more than two decades since my father’s death. She’d aged slowly in that chair, retiring first to read books and work her needlepoint, and then, when her eyes began to fail, to watch public television from dawn until she fell asleep in front of it after her evening meal. In the last year or two, she would sit in the chair and not even bother to turn on the television. Often she placed the twisted skeins of yarn that my older daughter, Emily, still sent each Christmas, in the center of her lap. She petted them the way some old women might pet cats.

I thanked Mrs. Castle and assured her I would handle everything.

“You know it’s time,” she said, turning toward me on the front stoop. “She’s been in the house alone an awfully long while.”

“I know,” I said, and shut the door.

Mrs. Castle walked down the steps of my mother’s front porch with three empty dishes of various sizes she had found in the kitchen and that she claimed to be hers. I didn’t doubt it. My mother’s neighbors were a godsend. When I was young, my mother had railed against the Greek Orthodox church down the road, calling its parishioners, for no reason that made sense, “those stupid Holy-Rolling Poles.” But it was this congregation that had often called upon its ranks to make sure the cranky old woman who had lived forever in the run-down house got fed and clothed. If occasionally she got robbed, well, it was precarious to be a woman living alone.

“People are living in my walls,” she had said to me more than once, but it was only when I found a condom lying beside my childhood bed that I’d put two and two together. Manny, a boy who occasionally repaired things for my mother, was bringing girls into her upstairs rooms. I had talked to Mrs. Castle and hired a locksmith. It was not my fault my mother refused to move.

“Mother,” I said, calling the name only I, as her sole child, had the right to call her. She looked up at me and smiled.

“Bitch,” she said.

The thing about dementia is that sometimes you feel like the afflicted person has a trip wire to the truth, as if they can see beneath the skin you hide in.

“Mother, it’s Helen,” I said.

“I know who you are!” she barked at me.

Her hands clasped the curved ends of the armrests, and I could see how hard she pressed, her anger flaring up and out at me like involuntary claws.

“That’s good,” I said.

I stood there a moment longer, until it felt like an established fact. She was my mother and I was her daughter. I thought we could go forward from this into our usual unpleasant encounter.

I walked over to the windows and began to draw up the metal blinds by the increasingly threadbare cloth tape that bound them. Outside, the yard of my childhood was so overgrown it was difficult to make out the original shapes of the bushes and trees, those places I had played with other children until my mother’s behavior began to garner a reputation outside our house.

“She steals,” my mother said.

My back was to her. I was looking at a vine that had crawled into the huge fir tree in the corner of the yard and consumed the shed where my father had once done carpentry. He had always been happiest inside that space. On my darkest days, I had come to imagine him there, laboriously sanding the round wooden globes that had replaced all his other projects.

“Who steals?”

“That bitch.”

I knew she was talking about Mrs. Castle. The woman who daily made sure my mother had woken up. Who brought her the Philadelphia Inquirer and not infrequently cut flowers from her own yard and placed them in plastic iced-tea pitchers that wouldn’t shatter if my mother knocked them over.

“That’s not true,” I told her. “Mrs. Castle is a lovely woman who takes good care of you.”

“What happened to my blue Pigeon Forge bowl?”

I knew the bowl and realized I had not seen it for weeks. In my youth it had always held what I thought of as imprisoned food-walnuts and Brazil nuts and filberts that my father would crack and dig out with a tiny fork.

“I gave it to her, Mother,” I lied.

“You what?”

“She’s been so wonderful and I knew she liked it, and so I just gave it to her one day when you were napping.”

Help doesn’t come free, I felt like telling her. These people owe you nothing.

My mother looked at me. It was a horrible bottomless look. She pouted first, her lower lip jutting out and then quivering. She was going to cry. I left the room and walked to the kitchen. Whenever I came, I found good reason to spend many of the hours I was supposed to be with my mother in every room of the house but the one in which she sat. I heard the low moan begin that I’d been hearing all my life. It was a moan the notes of which were orchestrated to elicit pity. My father had always been the one to run to her. After his death, it fell to me. For more than twenty years, with greater or lesser diligence, I had been attending to her, rushing over when she called saying her heart would burst, or taking her on increasing rounds of doctors’ visits as she aged.

Late in the afternoon of that day, I was in the screened-in back porch, sweeping out the straw mat. I had left the door open a crack so that I could hear her. Then into the cloud of dust that surrounded me came the unmistakable odor of shit. My mother had needed to go to the bathroom but couldn’t get up.

I dropped the broom and ran to my mother. She had not, as I may have momentarily hoped, died and suffered the resultant loosening of bowels. Dead in her own home as she might have wished. Instead, she sat in her chair, having soiled herself.

“Number two!” she said. This time, the smile was different than the smile of Bitch. Bitch had had life to it. This smile was alien to me. It held neither fear nor malice.

Often, when I recounted to my youngest, Sarah, the events of a given day, she told me that no matter how much she loved me, she wasn’t going to strip and diaper me when I grew old. “I’ll hire someone,” she said. “I’ve never heard a better incentive for hitting the big time than avoiding that.”

The smell had filled the room within seconds. I walked back to the porch twice to take in huge drafts of dusty air and could think of nothing else but presenting my mother in the way she would have wanted to be seen. I knew I was going to have to call the ambulance. I knew, as I had for some time, that my mother was heading out of this life, but I did not want her arriving at the hospital caked in shit. I should say I knew she would not want that, and so what had mattered most to her throughout her life-appearances-became what mattered most to me.